Morphology of Different Parts of Medicinal Plant

| Home | | Pharmacognosy |Chapter: Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry : Morphology of Different Parts of Medicinal Plant

Arrangements of plants into groups and subgroups are com-monly spoken as classification. Various systems of classifying plants have gradually developed during past few centuries which have emerged as a discipline of botanical science known as Taxonomy or Systematic botany.

MORPHOLOGY OF DIFFERENT PARTS OF MEDICINAL PLANT

INTRODUCTION

Arrangements of plants into groups and subgroups are commonly spoken as classification. Various systems of classifying plants have gradually developed during past few centuries which have emerged as a discipline of botanical science known as Taxonomy or Systematic botany. The Taxonomy word is derived from two Greek words ‘Taxis’ meaning an arrangement and ‘nomos’ meaning laws. Therefore, the systemization of our knowledge about plants in an orderly manner becomes subject matter of systematic botany.

The aim and objective of taxonomy is to discover the similarities and differences in the plants, indicating their closure relationship with their descents from common ancestry. It is a scientific way of naming, describing and arranging the plants in an orderly manner.

The classification of plants may be based upon variety of characters possessed by them. Features like specific morphological characters, environmental conditions, geographical distribution, colours of flowers and types of adaptations or reproductive characteristics can be used as a base for taxonomical character.

HISTORY

Many attempts were made in the earlier days to name and distinguish the plants as well as animals. Earliest mentions of classifications are credited to the Greek scientist Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) who is also called as the father of natural history. Aristotle attempted a simple artificial system for classifying number of plants and animals on the basis of their morphological and anatomical resemblances. It worked with great success for more than two thousand years.

Theophrastus (370–285 B.C.), the first taxonomist who wrote a systematic classification in a logical form was a student of Aristotle. He attempted to extend the botanical knowledge beyond the scope of medicinal plants.

Theophrastus classified the plants in about 480 taxa, using primarily the most obvious morphological characteristics, i.e. trees, shrubs, under-shrubs, herbs, annuals, biennials and perennials. He recognized differences based upon superior and inferior ovary, fused and separate petals and so on. He is called father of botany. Several of the names mentioned by him in his treatise, ‘De Historia Plantarum’ was later taken up by Linnaeus in his system of classification.

A. P. de Tournfort (1658–1708) carried further the promotional work on genus. He had a clear idea of genera and many of the names used by him in his Institutions Rei Herbariae (1700) were adopted by Linnaeus. Tournfort’s system classified about 9000 species into 698 genera and 22 classes. This system although artificial in nature was extremely practical in its approach.

Most of the taxonomists after Tournfort used the relative taxonomic characterization as a basis for classification. This natural base helped to ascertain the nomenclature and also showed its relative affinities with one another. All the modern systems of classification are thus natural systems.

John Ray (1682), an English Botanist used a natural system based on the embryo characteristics. Most impor-tant of his works were Methodus Plantarum Nova (1682), Historia Plantarum (1686) and Synopsis Methodica Stirpium Britanicarum (1698). He classified the plants into two main groups: Herbae, with herbaceous stem and Arborae, with woody stem.

The main groups of flowerless and flowering plants were subdivided distinctly into 33 smaller groups. He divided flowering plants in monocotyledonae and dicoty-ledonae, which later worked as a great foundation for the further developments of systematic botany

Carrolus Linnaeus (1707–1778), a Swedish botanist, introduced the system of binomial nomenclature. His artificial system was based oh particular names of a substantive and adjective, nature. It is best known as binomial system of nomenclature in which the first general name indicates the genus and the second specific name denotes the species. Linnaeus characterized and listed about 4378 different species of plants and animals in his works Species Plantarum and Genera Plantarum (1753). He classified plants on the basis of reproductive organs, i.e. stamens and carpels—and hence this system is also known as the sexual system of classification. According to this system, plants are divided into 24 classes having 23 phanerogams and one cryptogam. Phanerogams were classified on the basis of unisexual and bisexual flowers. Further classification is based on the number and types of stamens and carpels.

A French Botanist A. P. de Candolle (1819) extensively worked and improved the natural system of classification. Along with the recognition of cotyledons, corolla and stamen characteristics, Candolle introduced the arrangement of fibrovascular bundles as a major character. He also provided a classification system for lower plants; Candolle mainly divided plants into vascular and cellular groups, i.e. plants with cotyledons and without cotyledons. There groups were further divided and subdivided on the basis of cotyledons and floral characteristics.

Bentham and Hooker’s System

George Bentham (1830–1884) and Joseph Hooker (1817– 1911) two British Botanists, adopted a very comprehensive, natural system of classification in their published work Genera Plantarum (1862–1883), which dominated the botanical science for many years. It is an extension of Candolle’s work.

According to this system, the plant kingdom comprises about 97,205 species of seed plants which are distributed in 202 orders and were further divided in families. Dicotyledons have been divided in three divisions on the basis of floral characteristics namely: polypetalae, gamopetalae and mono-chlamydeae—all the three divisions consisting of total 163 families. Polypetalae have both calyx and corolla with free petals and indefinite number of stamens along with carpels. Gamopetalae have both calyx and corolla, but the latter is always gamopetalous or fused. Stamens are definite and epipetalous along with carpels. In monochlamydeae flowers are incomplete because of the absence of either calyx or corolla, or both the whorls. It generally includes the families which do not come under the above two subclasses.

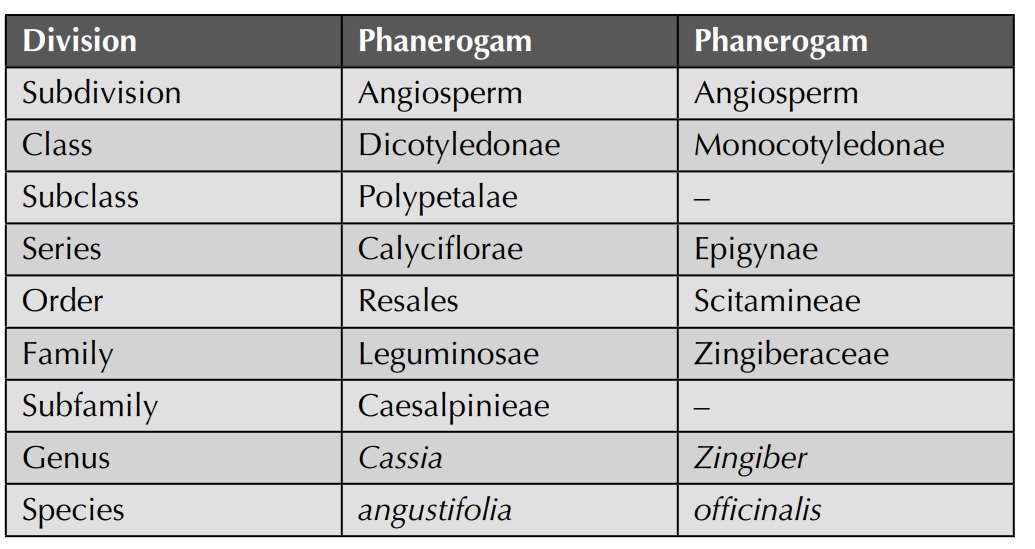

Following the above scheme of classification Indian senna, Cassia angustifolia and Ginger, Zingiber officinalis may be referred to its systematic position as mentioned in Table below

Adolf Engler (1844–1930), a German Botanist published his system of classification in Die Naturlichen Pflanzenfamilien in 23 volumes, covering the whole plant kingdom. The increasing complexity of the flowers is considered for clas-sification. Engler believed that woody plants with unisexual and apetalous flowers are most primitive in origin. This is a natural system which is based on the relationships and is compatible with evolutionary principles.

Hutchinson’s System of Classification

A British systematic Botanist J. Hutchinson published his work, The Families of Flowering Plants in 1926 on Dicotyle-dons and in 1934 on monocotyledons. Hutchinson made it clear that the plants with sepals and petals are more primitive than the plants without petals and sepals on the assumption that free parts are more primitive than fused ones. He also believed that spiral arrangement of floral parts, numerous free stamens and hermaphrodite flowers are more primitive than unisexual flowers with fused stamens. He considered monochlamydous plants as more advanced than dicotyledons. Hutchinson’s system indicates the concept of phylogenetic classification and seems to be an advanced step over the Bentham and Hooker system of classification. Hutchinson accepted the older view of woody and herbaceous plants and fundamentally called them as Lignosae and Herbaceae. He revised the scheme of classifi-cation in 1959. Hutchinson placed the gymnosperms first, then the dicotyledons and lastly the monocotyledons.

H. H. Rusby (1931) worked on phylogenic classification. His work is the scathing criticism on the phylogenic system attempted by M. C. Nair, ‘Angiosperm Phylogeny on a Chemical basis.’ While criticizing M. C. Nair, he indicated that the taxonomists need to study and use all the criteria including chemical nature while working on phylogenic system. He stubbornly criticized a publication on Cinchona that when the whole genus has been thoroughly investigated for its morphology; chemistry, reproduction, embryology, horticulture, ecology and geography, all the information is ignored in the chemotaxonomical study which is a great misfortune to Cinchona literature.

M.P. Morris (1954) worked on chemotaxonomy of toxic cyanogenetic glycosides of Indigofera endecaphylla and pointed out that p-nitropropionic acid, a hydrolysis product of Hiptagenic acid, occurs in a free state in the plants. His work provided the direction to chemotaxonomy of cyano-genetic principles.