Muscular System

| Home | | Anatomy and Physiology | | Anatomy and Physiology Health Education (APHE) |Chapter: Anatomy and Physiology for Health Professionals: Support and Movement: Muscular System

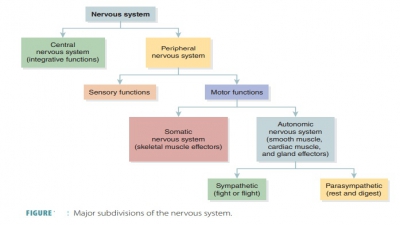

Skeletal muscles usually function in groups, with the nervous system stimulating the desired muscles to perform the intended function.

Muscular

System

After

studying this chapter, readers should be able to:

1. Distinguish

between the origin and insertion of a skeletal muscle.

2. Differentiate

between flexion and extension.

3. Differentiate

between parallel, convergent, pennate, and circular muscles.

4. Which

type of lever system is most common in the skeletal muscles?

5. Identify

the actions of the rhomboid major, subclavius, and trapezius muscles.

6. Explain

the movements of the deltoid, pectoralis major, and teres major.

7. Name

the muscles of the abdominal wall and explain the action of the rectus

abdominis.

8. Explain

the muscles that flex and extend the thigh.

9. Describe

the quadriceps femoris group and the function of the muscles it contains.

10. Describe

the function of the gastrocnemius.

Overview

Skeletal muscles usually function

in groups, with the nervous system stimulating the desired muscles to perform

the intended function. A muscle that con-tracts to provide most of a desired

movement is called a prime mover or agonist. A good example is the pectoralis major muscle, which is a prime mover

of arm flexion. Other muscles, known as synergists, work with a prime mover to make its action more effective by adding a

small amount of additional force. For example, when you bend your forearm, the

ago-nist muscles are the biceps and the synergists are the triceps. In muscles

that cross several joints, contrac-tion causes movement at all the spanned

joints unless other muscles act as stabilizers of the joints. Other flex-ors

may cause some undesirable movements in a joint, but synergists prevent this

and allow the total force of the prime mover to occur in the desired

directions. Some synergists, known as fixators,

may also assist an agonist by preventing another joint from moving to stabilize

the origin of the agonist. Fixator muscles run-ning from the axial skeleton to

the scapula cause the scapula to be immobilized. Only desired movements can

then occur at the shoulder joint. The muscles that help maintain upright

posture are fixators.

Other muscles act as antagonists to prime

mov-ers. They cause movement in the opposite direction. In the earlier example,

the triceps are the antagonists to the biceps. Smooth body movement depends on

antagonists relaxing while prime movers contract. Muscles may work opposite to

each other or together to control various movements. Antagonists and their

prime movers are situated on the opposite sides of joints across which they

function. An example is the pectoralis major, which acts as an antagonist to

the latissimus dorsi, the prime mover that extends the arm. It is important to

understand that antagonists can actually also be prime movers such as

latissimus dorsi when it acts as the prime mover of arm extension.

Origins and Insertions

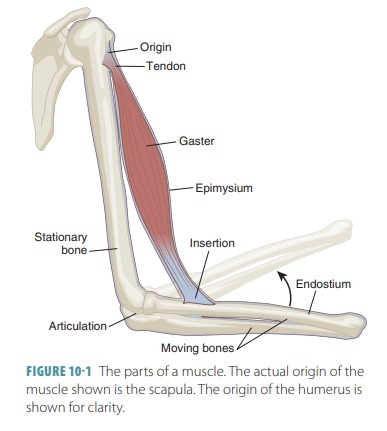

One end of a skeletal muscle

usually is fastened to a relatively immovable part (origin) at a movable joint. The other end connects to a movable part (insertion) on the

other side of the joint. As contraction occurs, the insertion is pulled toward

the origin. There may be more than one origin or insertion such as in the

biceps brachii muscle of the arm. When this muscle contracts, the insertion

being pulled toward its origin causes the forearm to flex at the elbow (FIGURE 10-1). Muscle

con-traction produces specific actions

or movements.

The head of a muscle is the part

closest to its origin. The term flexion

describes a decrease in the angle of a joint, for example, a movement of the

fore-arm that causes it to bend at the elbow. The term extension describes an increase in the angle of a joint, for example, a movement of the

forearm that straightens the elbow.

Arrangement of Skeletal Muscles

Skeletal muscles, according to

the arrangement of their fascicles, are divided into four distinct types:

parallel muscles, convergent muscles, pennate mus-cles, and circular muscles.

The pennate muscles are subdivided into unipennate, bipennate, and multipennate muscles.

Parallel Muscles

Most skeletal muscles are classified as parallel muscles, in which the fascicles are parallel to the long axes. Some are flat muscular bands with broad attachments called aponeuroses at each end, whereas others are thick and cylindrical having tendons at one or both ends. An example of a flat parallel muscle is the sartorius muscle, located in the thigh. When they are thick and cylindrical, they have a spindle shape with a central body. An example of a parallel muscle is the biceps brachii, which has a spindle shape and an expanded body. Sometimes, such spindle-shaped muscles are referred to as fusiform muscles.

Convergent Muscles

In a convergent

muscle, the muscle fascicles extend

over a broad area, converging on a single attachment site. The muscle may pull

on a tendon, aponeurosis, or a slender band of collagen fibers. This band is

known as a raphe. An example of a convergent muscle is the pectoralis major, which is triangular or fan-shaped.

Pennate Muscles

In a pennate

muscle, the fascicles create a com-mon

angle with the tendon and muscle fibers pull at an angle. This means pennate

muscles do not move tendons as far as parallel muscles do, but they have more

tension because they have more muscle fibers and myofibrils. The fascicles and

muscle fibers are short and obliquely attached to the central tendon funning

the entire length of the muscle. An example of a unipennate muscle is the extensor digitorum of the leg, which has

its fascicles inserted into just one side of the tendon. One example of a

bipennate muscle is the rectus femoris in

the thigh, which has fascicles inserted into

the tendon from opposite sides. It resembles the shape of a feather. One

multipennate muscle is the del-toid of

the shoulder, which appears as many feather

located side by side, with each of them inserted into one large tendon.

Circular

Muscles

In a circular

muscle or sphincter, the fascicles are arranged around an opening in a

concentric pattern. Muscle contractions cause a decrease in the diameter of the

opening, such as the orbicularis oris

muscle of the mouth or the orbicularis

oculi muscle of the eye.

Arrangement of Fascicles

The range of motion and strength

of a muscle are based on the arrangement of its fascicles. Skeletal muscle

fibers can shorten to approximately 70% of their resting length when they

contract. Therefore, longer and more parallel muscle fibers, in compar-ison to

a muscle’s long axis, means the more the muscle is able to shorten. Parallel

fascicle arrange-ments offer the most ability to shorten, but are not as strong

as other types of fascicle arrangements. The power of a muscle is based on the

number of muscle fibers in it. More muscle fibers offer more strength. For

example, bipennate and multipennate muscles have more fibers and are very

strong while only shortening slightly.

1. Define

the terms origin and insertion.

2. Differentiate

between flexion and extension.