Protein Misfolding

| Home | | Biochemistry |Chapter: Biochemistry : Structure of Proteins

Protein folding is a complex process that can sometimes result in improperly folded molecules. These misfolded proteins are usually tagged and degraded within the cell.

PROTEIN MISFOLDING

Protein folding is a

complex process that can sometimes result in improperly folded molecules. These

misfolded proteins are usually tagged and degraded within the cell. However,

this quality control system is not perfect, and intracellular or extracellular

aggregates of misfolded proteins can accumulate, particularly as individuals

age. Deposits of misfolded proteins are associated with a number of diseases.

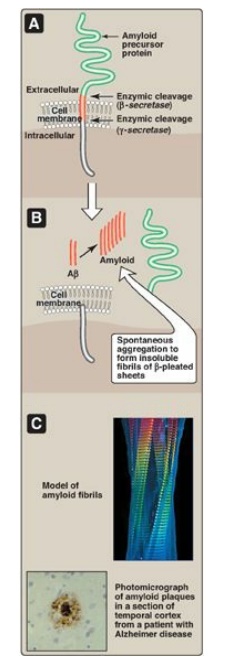

A. Amyloid diseases

Misfolding of proteins

may occur spontaneously or be caused by a mutation in a particular gene, which

then produces an altered protein. In addition, some apparently normal proteins

can, after abnormal proteolytic cleavage, take on a unique conformational state

that leads to the formation of long, fibrillar protein assemblies consisting of

β-pleated sheets. Accumulation of these insoluble, spontaneously aggregating

proteins, called amyloids, has been implicated in degenerative diseases such as

Parkinson and Huntington and particularly in the age-related neurodegenerative

disorder, Alzheimer disease. The dominant component of the amyloid plaque that

accumulates in Alzheimer disease is amyloid β (Aβ), an extracellular peptide

containing 40–42 amino acid residues. X-ray crystallography and infrared

spectroscopy demonstrate a characteristic β-pleated sheet conformation in

nonbranching fibrils. This peptide, when aggregated in a β-pleated sheet

configuration, is neurotoxic and is the central pathogenic event leading to the

cognitive impairment characteristic of the disease. The Aβ that is deposited in

the brain in Alzheimer disease is derived by enzymic cleavages (by secretases)

from the larger amyloid precursor protein, a single transmembrane protein

expressed on the cell surface in the brain and other tissues (Figure 2.13). The

Aβ peptides aggregate, generating the amyloid that is found in the brain

parenchyma and around blood vessels. Most cases of Alzheimer disease are not

genetically based, although at least 5% of cases are familial. A second biologic

factor involved in the development of Alzheimer disease is the accumulation of

neurofibrillary tangles inside neurons. A key component of these tangled fibers

is an abnormal form (hyperphosphorylated and insoluble) of the tau (τ) protein,

which, in its healthy version, helps in the assembly of the microtubular

structure. The defective τ appears to block the actions of its normal

counterpart.

Figure 2.13

Formation of amyloid plaques found in Alzheimer disease (AD). [Note: Mutations

to presenilin, the catalytic subunit of γ-secretase, are the most common cause

of familial AD.]

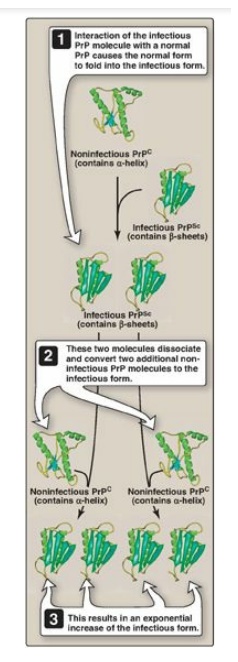

B. Prion diseases

The prion protein (PrP)

has been strongly implicated as the causative agent of transmissible spongiform

encephalopathies (TSEs), including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans, scrapie

in sheep, and bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle (popularly called “mad

cow” disease). After an extensive series of purification procedures, scientists

were surprised to find that the infectivity of the agent causing scrapie in

sheep was associated with a single protein species that was not complexed with

detectable nucleic acid. This infectious protein is designated PrPSc (Sc =

scrapie). It is highly resistant to proteolytic degradation and tends to form

insoluble aggregates of fibrils, similar to the amyloid found in some other

diseases of the brain. A noninfectious form of PrPC (C = cellular), encoded by

the same gene as the infectious agent, is present in normal mammalian brains on

the surface of neurons and glial cells. Thus, PrPC is a host protein. No

primary structure differences or alternate posttranslational modifications have

been found between the normal and the infectious forms of the protein. The key

to becoming infectious apparently lies in changes in the three-dimensional

conformation of PrPC. It has been observed that a number of α-helices present

in noninfectious PrPC are replaced by β-sheets in the infectious form (Figure

2.14). It is presumably this conformational difference that confers relative

resistance to proteolytic degradation of infectious prions and permits them to

be distinguished from the normal PrPC in infected tissue. The infective agent

is, thus, an altered version of a normal protein, which acts as a “template”

for converting the normal protein to the pathogenic conformation. The TSEs are

invariably fatal, and no treatment is currently available that can alter this

outcome.

Figure 2.14

One proposed mechanism for multiplication of infectious prion agents. PrP =

prion protein; PrPc = prion protein cellular; PrPSc = prion protein scrapie.

Related Topics