Fundamental features of microbiology

| Home | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology |Chapter: Pharmaceutical Microbiology : Fundamental features of microbiology

Microorganisms differ enormously in terms of their shape, size and appearance and in their genetic and metabolic characteristics. All these properties are used in classifying microorganisms into the major groups with which many people are familiar, e.g. bacteria, fungi, protozoa and viruses, and into the less well known categories such as chlamydia, rickettsia and mycoplasmas.

FUNDAMENTAL FEATURES OF MICROBIOLOGY

Introduction

Microorganisms

differ enormously in terms of their shape, size and appearance and in their

genetic and metabolic characteristics. All these properties are used in classifying

microorganisms into the major groups with which many people are familiar, e.g.

bacteria, fungi, protozoa and viruses, and into the less well known categories

such as chlamydia, rickettsia and mycoplasmas. The major groups are the subject

of individual chapters immediately following this, so the purpose here is not

to describe any of them in great detail but to summarize their features so that

the reader may better understand the distinctions between them. A further aim

of this chapter is to avoid undue repetition of information in the early part

of the book by considering such aspects of microbiology as cultivation,

enumeration and genetics that are common to some, or all, of the various types

of microorganism.

Viruses, viroids and prions

Viruses

do not have a cellular structure. They are particles composed of nucleic acid

surrounded by protein; some possess a lipid envelope and associated

glycoproteins, but recognizable chromosomes, cytoplasm and cell membranes are

invariably absent. Viruses are incapable of independent replication as they do

not contain the enzymes necessary to copy their own nucleic acids; as a

consequence, all viruses are intracellular parasites and are reproduced using

the metabolic capabilities of the host cell. A great deal of variation is

observed in shape (helical, linear or spherical), size (20–400 nm) and nucleic

acid composition (single or double-stranded, linear or circular RNA or DNA), but

almost all viruses are smaller than bacteria and they cannot be seen with a

normal light microscope; instead they may be viewed using an electron

microscope which affords much greater magnification.

Viroids

(virusoids) are even simpler than viruses, being infectious particles

comprising single-stranded RNA without any associated protein. Those that have

been described are plant pathogens, and, so far, there are no known human

pathogens in this category, although human hepatitis D virus shares some features

in common with viroids, and may have originated from them.

Prions

are unique as infectious agents in that they contain no nucleic acid. A prion

is an atypical form of a mammalian protein that can interact with a normal

protein molecule and cause it to undergo a conformational change so that it, in

turn, becomes a prion and ceases its normal function. Prions are the agents

responsible for transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, e.g. Creutzfeldt–Jakob

disease (CJD) and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). They are the simplest

and most recently recognized agents of infectious disease, and are important in

a pharmaceutical context owing to their extreme resistance to conventional

sterilizing agents like steam, gamma radiation and disinfectants.

Prokaryotes and eukaryotes

The

most fundamental distinction between the various microorganisms having a

cellular structure, is their classification into two groups—the prokaryotes and

eukaryotes— based primarily on their structural characteristics and mode of

reproduction. Expressed in the simplest possible terms, prokaryotes are the

bacteria and archaea, and eukaryotes are all other cellular microorganisms,

e.g. fungi, protozoa and algae. The crucial difference between these two types

of cell is the possession by the eukaryotes of a true cell nucleus in which the

chromosomes are separated from the cytoplasm by a nuclear membrane. The

prokaryotes have no true nucleus; they normally possess just a single

chromosome that is not separated from the other cell contents by a membrane.

Other major distinguishing features of the two groups are that prokaryotes are

normally haploid (possess only one copy of the set of genes in the cell) and

reproduce asexually; eukaroyotes, by contrast, are usually diploid (possess two

copies of their genes) and normally have the potential to reproduce sexually. The

capacity for sexual reproduction confers the major advantage of creating new

combinations of genes, which increases the scope for selection and evolutionary

development. The restriction to an asexual mode of reproduction means that the

organism in question is heavily reliant on mutation as a means of creating

genetic variety and new strains with advantageous characteristics, although

many bacteria are able to receive new genes from other strains or species.

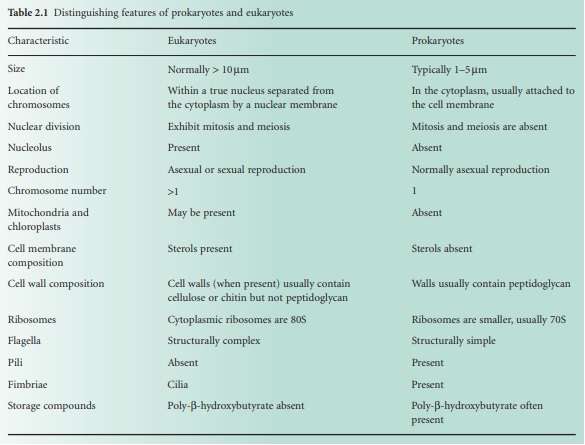

Table 2.1 lists some distinguishing features of the prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Bacteria and archaea

Bacteria are essentially unicellular, although some species arise as sheathed chains of cells. They possess the properties listed under prokaryotes in Table 2.1 but, like viruses and other categories of microorganisms, exhibit great diversity of form, habitat, metabolism, pathogenicity and other characteristics. The bacteria of interest in pharmacy and medicine belong to the group known as the eubacteria. The other subdivision of prokaryotes, the archaea, have no pharmaceutical importance, and although formerly considered largely to comprise organisms capable of living in extreme environments (e.g. high temperatures, extreme salinity or pH) or organisms exhibiting specialized modes of metabolism (e.g. by deriving energy from sulphur or iron oxidation or the production of methane) they are now known to occur in a wide variety of habitats

The

eubacteria are typically rod shaped (bacillus), spherical (cocci), curved or

spiral cells of approximately 0.5–5.0 mm (longest dimension) and are divided

into two groups designated Gram-positive and Gram-negative according to their

reaction to a staining procedure developed in 1884 by Christian Gram. Although

all the pathogenic species are included within this category, there are very

many other eubacteria that are harmless or positively beneficial. Some of the

bacteria that contaminate or cause spoilage of pharmaceutical materials are

saprophytes, i.e. they obtain their energy by decomposition of animal and vegetable

material, while many could also be described as parasites (benefiting from

growth on or in other living organisms without causing detrimental effects) or

pathogens (parasites damaging the host). Rickettsia and chlamydia are types of

bacteria that are obligate intracellular parasites, i.e. they are incapable of

growing outside a host cell and so cannot easily be cultivated in the

laboratory. Most bacteria of pharmaceutical and medical importance possess cell

walls (and are therefore relatively resistant to osmotic stress), grow well at

temperatures between ambient and human body temperature, and exhibit wide

variations in their requirement for, or tolerance of, oxygen. Strict aerobes

require atmospheric oxygen, but for strict anaerobes oxygen is toxic. Many

other bacteria would be described as facultative anaerobes (normally growing

best in air but can grow without it) or micro-aerophils (preferring oxygen concentrations

lower than those in normal air).

Fungi

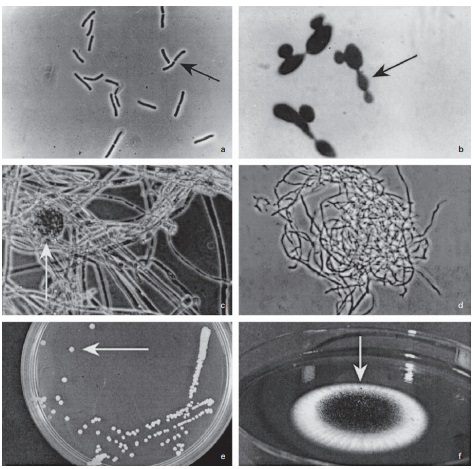

Fungi are structurally more complex and varied in appearance than bacteria and, being eukaryotes, differ from them in the ways described in Table 2.1. Fungi are considered to be non-photosynthesizing plants, and the term fungus covers both yeasts and moulds, although the distinction between these two groups is not always clear. Yeasts are normally unicellular organisms that are larger than bacteria (typically 5–10 µm) and divide either by a process of binary fission (Figure 2.1a) or budding (whereby a daughter cell arises as a swelling or protrusion from the parent that eventually separates to lead an independent existence, Figure 2.1b). Mould is an imprecise term used to describe fungi that do not form fruiting bodies visible to the naked eye, thus excluding toadstools and mushrooms. Most moulds consist of a tangled mass (mycelium) of filaments or threads (hyphae) which vary between 1 and over 50 µm wide (Figure 2.1c); they may be differentiated for specialized functions, e.g. absorption of nutrients or reproduction. Some fungi may exhibit a unicellular (yeastlike) or mycelial (mouldlike) appearance depending upon cultivation conditions. Although fungi are eukaryotes that should, in theory, be capable of sexual reproduction, there are some species in which this has never been observed. Most fungi are saprophytes with relatively few having pathogenic potential, but their ability to form spores that are resistant to drying makes them important as contaminants of pharmaceutical raw materials, particularly materials of vegetable origin.

Figure 2.1 (a) A growing culture of Bacillus megaterium in which cells about to divide by binary fission display constrictions (arrowed) prior to separation. (b) A growing culture of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae displaying budding (arrowed). (c) The mould Mucor plumbeus exhibiting the typical appearance of a mycelium in which masses of asexual zygospores (arrowed) are formed on specialized hyphae. (d) The bacterium Streptomyces rimosus displaying the branched network of filaments that superficially resembles a mould mycelium. (e) The typical appearance of an overnight agar culture of Micrococcus luteus inoculated to produce isolated colonies (arrowed). (f) A single colony of the mould Aspergillus niger in which the actively growing periphery of the colony (arrowed) contrasts with the mature central region where pigmented asexual spores have developed.

Protozoa

Protozoa

are eukaryotic, predominantly unicellular microorganisms that are regarded as animals

rather than plants, although the distinction between protozoa and fungi is not

always clear and there are some organisms whose taxonomic status is uncertain.

Many protozoa are free living motile organisms that occur in water and soil,

although some are parasites of plants and animals, including humans, e.g. the

organisms responsible for malaria and amoebic dysentery. Protozoa are not normally

found as contaminants of raw materials or manufactured medicines and the

relatively few that are of pharmaceutical interest owe that status primarily to

their potential to cause disease.