Cardiovascular Safety Signal Evaluation

| Home | | Pharmacovigilance |Chapter: Pharmacovigilance: NSAIDs - COX-2 Inhibitors – Risks and Benefits

These data are avail-able from the FDA website (FDA, 2001) and some were subsequently published in peer-reviewed journals.

CARDIOVASCULAR SAFETY SIGNAL

EVALUATION

As

results from VIGOR indicated that rofecoxib was associated with increased risk

of myocardial infarction, a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory

committee meeting was convened in February 2001 to review gastrointestinal and

cardiovascular safety data of rofecoxib and celecoxib. These data are

avail-able from the FDA website (FDA, 2001) and some were subsequently

published in peer-reviewed journals. In the US, revised package insert of

rofecoxib with updated safety information was released in April 2002 (Kweder,

2004).

BIOLOGICAL MECHANISM

As

the COX-2 inhibitors have minimal effects on COX-1 in gastric epithelium, they

have more favor-able gastrointestinal safety profile than the non-selective

NSAIDs. However, at the time of approval of celecoxib and rofecoxib,

pharmacologic stud-ies indicated that selective inhibition of COX-2 may

contribute to imbalance in the prostacyclin (prostaglandin I2) to

thromboxane ratio and result in thrombotic events (FitzGerald, 2004). COX-2 in

endothelium is responsible for the production of prostacyclin, which inhibits

platelet aggregation, causes vasodilatation, and prevents proliferation of

vascular smooth-muscle cells. On the other hand, the COX-1 in platelets, which

is not affected by the COX-2 inhibitors, is responsible for thromboxane A2

synthesis, and thromboxane A2 has the opposite effects of

prostacyclin, causing platelet aggregation, vasoconstriction, and vascular

proliferation. Theoret-ically, selective inhibition of COX-2 would allow the

physiologic effects of thromboxane to predomi-nate and result in adverse

cardiovascular outcomes (FitzGerald, 2003).

The

VIGOR investigators cited a study in healthy volunteers that showed different

effects on thrombox-ane A2 production and platelet aggregation

associated with different non-selective NSAIDs (Van Hecken et al., 2000). Ibuprofen 800 mg three times a day and sodium naproxen 550 mg twice a day in

healthy volun-teers showed substantial inhibition effects on throm-boxane A2

production and platelet aggregation, but how these pharmacologic findings

translate to preven-tion of myocardial infarction by naproxen needed to be

verified in clinical studies. The cardio-protective effects of naproxen would

have to be very power-ful in order to result in the VIGOR findings and support

the hypothesis that rofecoxib 50 mg per day was not associated with increased

risk of myocardial infarction.

CLINICAL TRIALS OF CELECOXIB AND ROFECOXIB

After

the results of clinical trials discussed during the February 2001 FDA advisory

committee meet-ing were made public, a group of independent inves-tigators

reviewed cardiovascular events observed in CLASS, VIGOR, and two unpublished

clinical trials of rofecoxib (Mukherjee, Nissen and Topol, 2001). The review

covered more cardiovascular data than that was published in the original CLASS

and VIGOR reports in 2000 as patients contributed more follow-up time and

cardiovascular events were independently adjudicated. Reviews of cardiovascular

safety data in the clinical development programs of celecoxib and rofecixb were

also published by manufacturers of the drugs from 2001 through 2003.

Celecoxib

No

increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death was found in the

celecoxib group in CLASS. The same finding was observed in patients who

received aspirin and those who did not receive aspirin during the trial

(Mukherjee, Nissen and Topol, 2001). The CLASS investigators carried out a

safety analy-sis and evaluated the risk of cardiovascular outcomes,

cerebrovascular outcomes, and peripheral vascular outcomes (White et al., 2002). No increased risk of

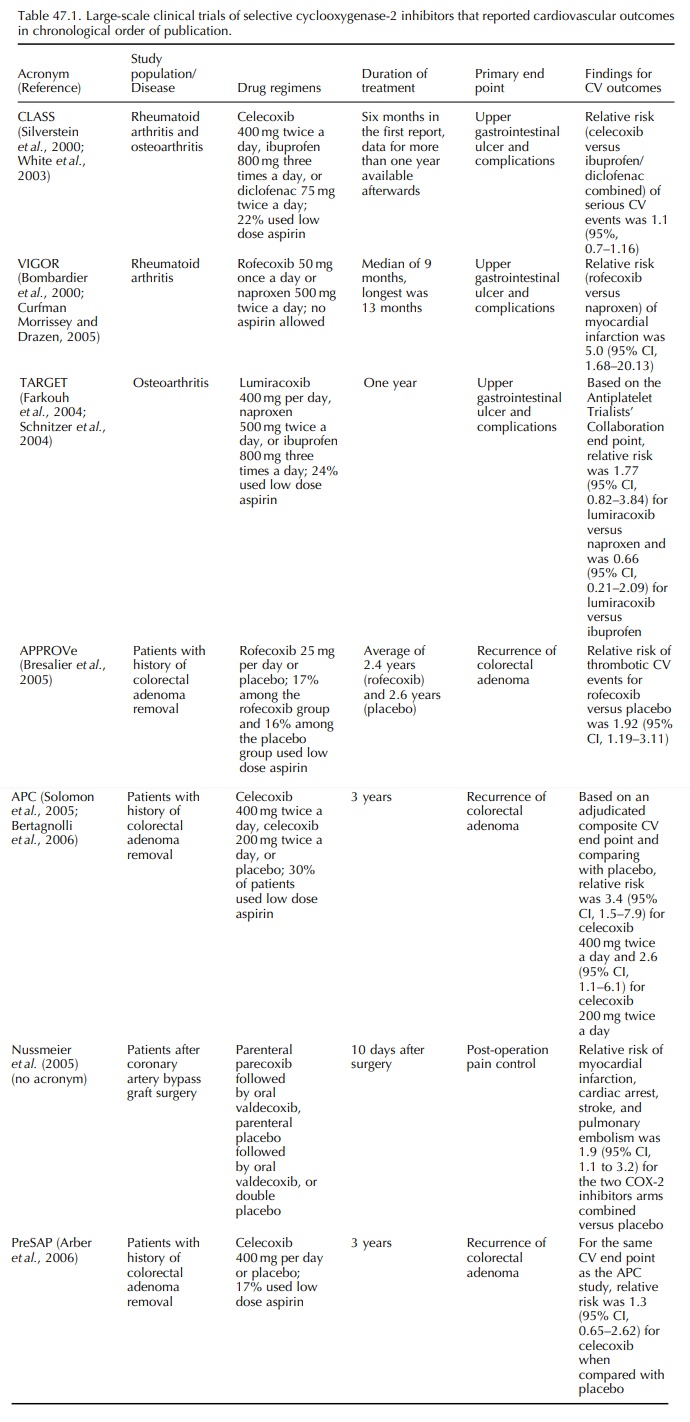

thromboembolic events was found among the cele-coxib group (Table 47.1). White

and colleagues combined data from 15 trials of celecoxib and used the

Anti-Platelet Trialists’ Collaboration (APTC) defini-tion of adverse

cardiovascular outcomes (Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration, 1994),

including cardiovas-cular, hemorrhagic and unknown death, myocardial

infarction, and cerebrovascular accident, as the end point of interest (White et al., 2003). A relative risk of 1.06

(95% CI, 0.70–1.61) was found for the celecoxib (all doses) versus

non-selective NSAID comparison.

Rofecoxib

Two

unpublished studies, 085-2001 and 090-2001, of rofecoxib reported by Mukherjee

and colleagues in 2001 were three-arm trials of rofecoxib 12.5 mg per day,

nabumetone 1000 mg per day, and placebo for six weeks among patients with

osteoarthritis. Using low dose aspirin was not an exclusion criterion in both

trials. No difference in cardiovascular events was found between the rofecoxib-

and nabumetone-treated groups in 085-2001 and there was a non-significant

increase in the incidence of cardiovascular events in the rofecoxib versus

nabumetone comparison (1.5% versus, 0.5%) in 090-2001.

For

VIGOR, Mukherjee and colleagues reported incidence of serious thrombotic

cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction, unstable angina,

cardiac thrombus, resuscitated cardiac arrest, sudden or unexplained death,

ischemic stroke, and transient ischemic attacks in the treatment groups

(Mukherjee, Nissen and Topol, 2001). In addition, more adju-dicated cases of

serious cardiovascular events were reported at the February 2001 FDA advisory

commit-tee, which did not appear in the original VIGOR publication (Curfman,

Morrissey and Drazen, 2005). The VIGOR study protocol stated that history of

cere-brovascular events in the two years before the study, history of

myocardial infarction or coronary bypass in the year before the study, and

requirement for or ongo-ing treatment with aspirin, ticlopidine, or

anticoagu-lants were exclusion criteria. However, ‘requirement for aspirin

treatment’ was not objectively defined and was subjectively assessed by the

physicians who enrolled the patients. Mukherjee and colleagues reported a post-hoc

stratification of study subjects according to cardiovascular indication for

aspirin use, which was operationally defined as prior history of stroke,

transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarc-tion, unstable angina, angina

pectoris, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, or percutaneous coronary

inter-ventions. Only 321 (4%) of the 8076 enrolled subjects were

aspirin-indicated and no myocardial infarction occurred among aspirin indicated

patients. Relative risk of serious cardiovascular events was 4.89 (95% CI,

1.41–16.88) among the rofecoxib (50 mg per day) group in the full cohorts and

for the non-aspirin indi-cated subjects, the relative risk was 1.89 (95% CI,

1.03–3.45).

Scientists

from the manufacturer of rofecoxib and academic investigators analyzed the

safety database of clinical trials of rofecoxib and published three safety

reports after VIGOR. In the first report, Konstam and colleagues reviewed

combined data of more than 28 000 patients from 23 trials and used the APTC

defi-nition for cardiovascular end point (Konstam et al., 2001). Rofecoxib was associated with increased risk of APTC

events when compared with naproxen (rela-tive risk, 1.69, 95% CI, 1.07–2.69)

but there was no increased risk when rofecoxib was compared with placebo or

non-naproxen NSAIDs. Stratifying the rofecoxib group by dose and compared with

all NSAIDs, relative risk was 2.08 (95% CI, 0.57, 7.51) for rofecoxib 50 mg per

day and was 1.16 (95% CI, 0.25, 7.18) for rofecoxib 25 mg per day. Reicin and

colleagues reported results from pooled data from eight phase IIB or III trials

of rofecoxib, ibuprofen, diclofenac, nabumetone, or placebo for

osteoarthri-tis, with a total of 5435 patients (Reicin et al., 2002). Using the APTC end point and any arterial or venous

thrombotic cardiovascular adverse event as the outcome of interest, no

significantly increased cardiovascular risk was observed in the rofecoxib–

non-selective-NSAID and rofecoxib–placebo compar-isons. However, statistical

power was limited to detect a modest increase in cardiovascular risk among a

dataset of this size and these trials were short-term studies with no

information on potential effects among long-term use. In 2003, Weir and

colleagues reported safety data from the rofecoxib development program that

included short-term trials, long-term studies like VIGOR, and

placebo-controlled studies for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease (Weir et al., 2003). The results confirmed the

increased cardio-vascular risk for the rofecoxib–naproxen comparison, with a

relative risk of 1.61 (95% CI, 1.04–2.50) in pooled analysis for trials among

patients with rheuma-toid arthritis and/or osteoarthritis. No increased

cardiovascular risk was found for the rofecoxib– non-naproxen-NSAID comparison

or the rofecoxib– placebo comparison. These data pooling exercises were helpful

in the safety assessment of drugs, but the heterogeneity of the study

populations and treat-ment periods are major limitations. In the report by Weir

and colleagues, there were no stratified results based on dose and duration of

use for rofecoxib.

CARDIOPROTECTIVE EFFECTS OF NAPROXEN IN EPIDEMIOLOGY STUDIES

While

there has been pharmacologic basis for cardio-protective effects of naproxen

(Van Hecken et al., 2000), there has

been no reported clinical trial that specifically evaluated the risk of adverse

cardiovas-cular outcomes in a naproxen versus placebo compar-ison before VIGOR

or through 2005. The VIGOR results prompted more than 10 reports of

observa-tional studies that evaluated the association between naproxen use and

myocardial infarction, all of them were included in a meta-analysis conducted

by Jüni and colleagues (Jüni et al.,

2004). Reduced risk of myocardial infarction associated with naproxen was

reported in three case-control studies; reduced but non-significant risk was

reported in four studies; and small increased risk associated with naproxen was

reported in three studies. All these data taken together suggested a small

reduced risk, on the order of 15%, of myocardial infarction associated with

naproxen use. However, these findings did not support the hypothesis that

rofecoxib 50 mg per day did not increase risk of myocardial infarc-tion, as the

small reduction in risk associated with naproxen use could not adequately

explain the more than fourfold increase in risk of myocardial infarc-tion in

the rofecoxib–naproxen comparison observed in VIGOR.

OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES OF CELECOXIB AND ROFECOXIB

After

VIGOR, important information about population-based cardiovascular risk

associated with rofecoxib and celecoxib came from large observa-tional studies

with sufficient numbers of COX-2 inhibitors users in a real life setting. Ray

and colleagues reported that new users of high dose rofecoxib (more than 25 mg

per day) had an almost twofold increase in the risk of hospital admission for

acute myocardial infarction or death from coronary heart disease when compared

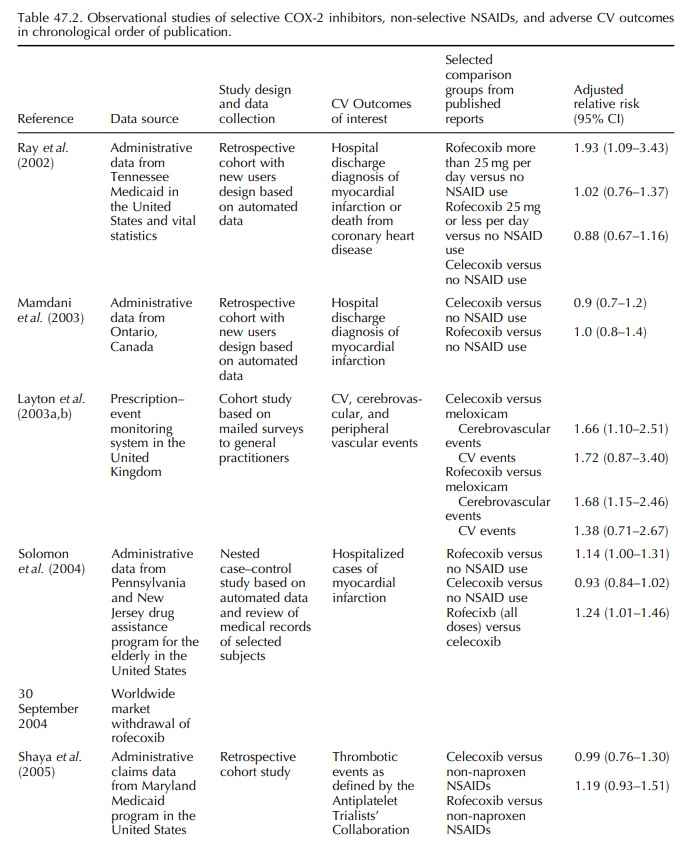

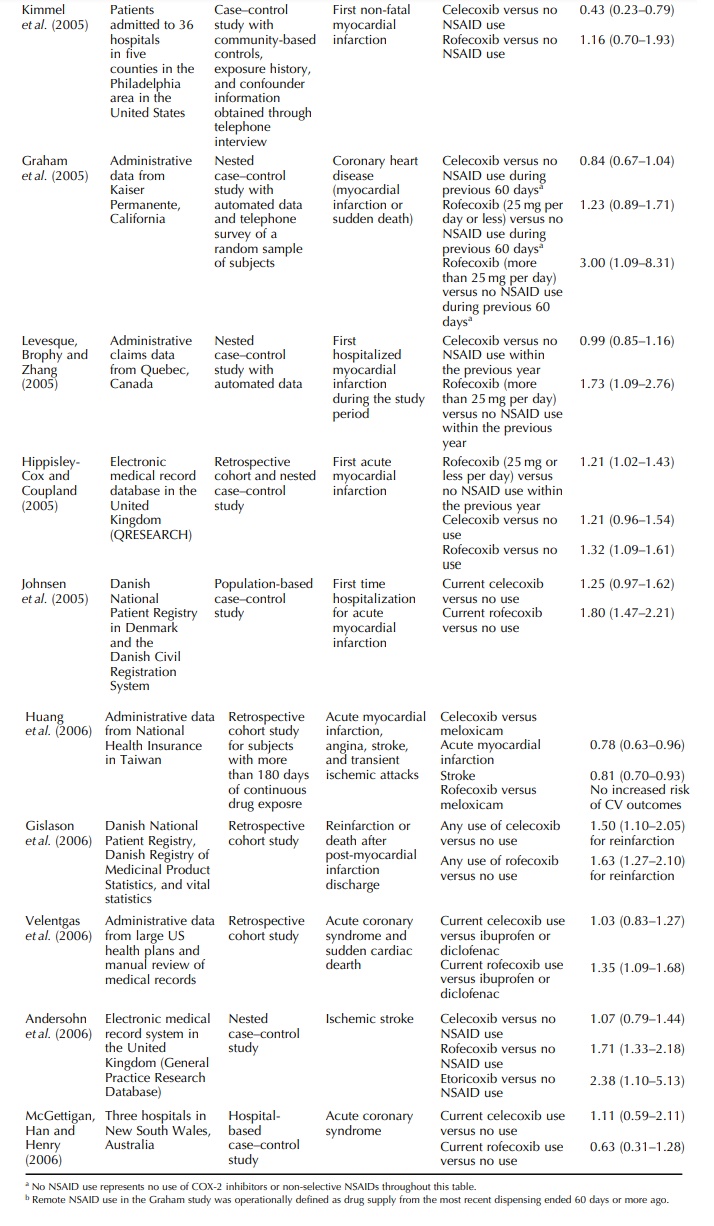

with those who did not receive any non-selective NSAID or COX-2 inhibitor (Ray et al., 2002; Table 47.2). No

statistically significant increased risk was observed among new users of lower

dose rofecoxib (25 mg or less per day), celecoxib, naproxen, or ibuprofen.

Three

other observational studies, one each from Canada, the UK, and the US, were

published before the market withdrawal of rofecoxib in September 2004 and are

summarized in Table 47.2. Mamdani compared new users of COX-2 inhibitors or

non-selective NSAIDs with subjects who did not use any COX-2 inhibitors or

non-selective NSAID and reported no increased risk in acute myocardial

infarc-tion in new users of celecoxib or rofecoxib (Mamdani et al., 2003).

The

UK study was based on the Prescription-Event Monitoring system and was reported

as two companion articles in the same journal in 2003 – one was a comparison

between celecoxib and meloxicam (Layton et

al., 2003a) and the other was a compari-son between rofecoxib and meloxicam

(Layton et al., 2003b). Outcomes of

interest were cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral venous thrombotic

events. Comparing with meloxicam, a preferential but not selective COX-2

inhibitor, and only adjusted for age and sex, celecoxib and rofecoxib were both

associated with increased risk of cerebrovascular events. Age-sex-adjusted

relative risk for cardiovas-cular events suggested an increased risk for both

drugs but the 95% confidence intervals for both relative risks included one.

The

manufacturer of rofecoxib funded a case-control study among members of

state-sponsored pharmacy benefit programs for residents aged 65 or older of New

Jersey and Pennsylvania in the US (Solomon et

al., 2004). Comparing rofecoxib with no use of non-selective NSAIDs or

COX-2 inhibitors, naproxen, ibuprofen, or other NSAIDs, relative risk estimates

for developing acute myocardial infarction were 1.14, 0.95, 1.21, and 1.17

respectively. Compar-ing celecoxib against the same drug groups, the relative

risk estimates ranged between 0.93 and 0.98. 95% CIs for these eight relative

risks all included one. Consis-tently higher relative risk of acute myocardial

infarc-tion was associated with the use of more than 25 mg per day of rofecoxib

than that for the use of 25 mg per day or less of rofecoxib when compared with

the same groups. No dose-dependent finding was observed for celecoxib.

Rofecoxib was associated with a 24% increased risk of hospitalized myocardial

infarction when compared with celecoxib (Table 47.2).

NON-THROMBOEMBOLIC ADVERSE CARDIOVASCULAR EVENTS

Other

adverse cardiovascular effects of COX-2 inhibitors have also been reported

after their approval. Whelton and colleagues conducted a 6-week clin-ical trial

of COX-2 inhibitors among patients 65 years or older with osteoarthritis and

stable medication-controlled hypertension and showed that the incidence of

increased systolic blood pressure was higher among patients randomly assigned

to receive 25 mg of rofecoxib per day than among those who received celecoxib

200 mg per day (Whelton et al.,

2002). Using automated administrative data from Ontario, Canada, Mamdani and

colleagues reported an increased risk of congestive heart failure among

rofe-coxib users but not celecoxib users (Mamdani et al., 2004).

SUMMARY OF SAFETY INFORMATION OF CELECOXIB AND ROFECOXIB THROUGH JULY 2004

Results

from VIGOR clearly indicated that rofecoxib 50 mg per day was associated with

higher risk of adverse cardiovascular thrombotic events. Epidemiol-ogy studies

reported by Ray and colleagues in 2002 and by Solomon and colleagues in 2004

corrobo-rated this finding. Whether the use of rofecoxib 25 mg or less per day

increased the risk of serious cardio-vascular thrombotic events was less

certain. On the other hand, no compelling evidence suggested that celecoxib use

was associated with increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes and as of

mid-2004 these results did not support a class effect of adverse cardiovascular

effects for the COX-2 inhibitors. In the label revision for rofecoxib in 2002,

increased cardiovascular risk observed from the VIGOR trial was noted and

recommendation that high dose rofe-coxib not to be used chronically was added

(Kweder, 2004).

Related Topics