Keys to Infection Prevention and Control

| Home | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology |Chapter: Pharmaceutical Microbiology : Public Health Microbiology: Infection Prevention And Control

There is no single ‘silver bullet’ to solve the challenge of HCAI. Infection prevention and control requires a combination of actions and activities, each of which provides an essential component to the whole.

KEYS TO INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL

There is no single ‘silver bullet’ to solve the challenge of HCAI.

Infection prevention and control requires a combination of actions and

activities, each of which provides an essential component to the whole.

Management And Organizational Commitment

The commitment of senior management to making infection prevention and

control a high priority sets a culture of a health of social care organization.

Management should monitor surveillance and audit data at all levels of the organization

(‘from board to ward’) and ensure that all the staff play their part. This

helps general a culture of pride in delivery of a quality service.

Surveillance

Up-to-date surveillance data on the incidence of key infections should be

collected, analysed and returned to the clinical units with minimum delay. In

this way the data are seen to be ‘real’ by the staff responsible for the care

of the patients. It is now mandatory in several countries to collect

surveillance data on MRSA infections (particularly bacteraemias), CDI, and some

type of surgical site infections. Although national data collection is focused

on whole hospitals or hospital groups, effective action within hospital depends

upon the data being assessed and acted upon in individual wards or other

clinical units, The essential nature of surveillance data is encapsulated in

the dictum ‘you have to measure it to manage it’.

Clinical Protocols

There are two main reasons why patients are at risk of developing an HCAI—their

underlying medical condition making them vulnerable to infections and the

treatment and clinical interventions they are subjected to. These interventions

often include invasive procedures that bypass the normal defences of the skin,

urinary and respiratory tract. It is, therefore, essential that clinical staff

exercise all due care and attention when performing these procedures. To this

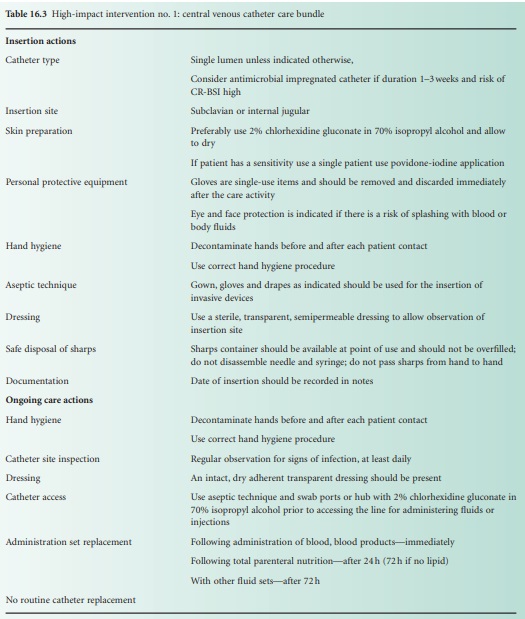

end, an approach to clinical practice has been developed variously known as

‘care bundles’ (in the USA in particular) and ‘high-impact interventions’ (HII;

the UK approach). These bundles are care protocols setting out in a simple

bullet-point format the five or six essential elements needed to minimize the

infection risk associated with the individual aseptic procedures. The aim is

for each element to be performed correctly on every occasion and the care

bundle/HII incorporates a simple audit tool for self-or peer-assessment on a

frequent and regular basis of the performance of the clinical staff doing those

procedures. The procedures that had been the main focus of the bundles comprise

the following invasive interventions:

central intravenous catheter insertion

and maintenance (Table 16.3)

•

peripheral intravenous cannula

insertion and maintenance

•

renal dialysis catheter insertion and

maintenance

•

surgical site infection (wound) care

•

care of ventilated patients

•

urinary catheter insertion and care.

For the HCAI programme in England these were set out in packages called

‘Saving Lives’ for secondary care and ‘Essential Steps’ for primary care use.

The packages were complemented by a care bundle for CDI and guidance presented

in a similar way based upon key elements for antibiotic prescribing, isolation

and cohorting of infected patients and the collection of blood cultures which

form the basis of the diagnosis of a bacteraemia.

Isolation And Segregation

One of the most basic and ancient approaches to preventing the spread of

infection (or ‘contagion’ in previous centuries) is isolation of the affected

patient. Segregation of infected patients from those vulnerable to infection

(including various forms of quarantine) is an essential element of all

infection prevention and control practice. It is particular important in HCAIs

where the infection often occurs in vulnerable or debilitated patients and in a

setting where transmission of infection between patients can occur readily. In

many hospitals, the number of single rooms available for patient isolation is

limited. The best use of the available rooms should be made for those with

infections, but where the capacity of single rooms is exceeded by the number of

cases of infection, it may then be necessary and appropriate for patients with

the same infection to be nursed together in a cohort ward physi-cally separated

from other ward areas and with dedicated staff who do not move between the

cohort ward and other clinical areas (i.e. cohorting should apply to nursing

staff as well as patients).

Hand Hygiene

One of the main routes of transmission

of HCAI pathogens such as MRSA is via the hands of healthcare workers as they

move between patients. For many years staff were recommended to wash their

hands between patient contacts and especially before and after performing

clinical procedures. However, very frequent hand washing is time consuming, can

damage the skin if done as often as should be required, and can also be quite

impracticable when there is inadequate provision of wash-hand basins for staff.

The answer to this problem has been the introduction of alcohol hand rubs that

can be used repeatedly and quickly at every point of patient contact. Alcohol

is highly effective against vegetative bacteria causing HCAI such as MRSA and

the Gram-negative bacteria. The hand rubs should be made available at every

patient bedside and in every clinical area, and at the entrance to cubicles and

single rooms. Personal dispensers can also be carried attached to a belt or the

clothing of healthcare staff to use as they move between patients. In many hospitals,

alcohol hand rub dispensers have also been placed at the hospital entrance

and/or at every ward entrance to emphasize to patients and visitors, as well as

staff, the absolute importance of hand hygiene. However, the crucial times and

places for hand hygiene relate to direct clinical contact with patients. The

hand hygiene campaign based on alcohol hand rubs has been promoted

internationally by the World Health Organization (WHO) and in the UK by the

National Patient Safety Agency through its ‘cleanyourhands’ campaign.

The WHO campaign high-lights the five opportunities (and requirements) for hand

hygiene:

• before touching a patient

• before clean/aseptic procedures

• after body fluid exposure/risk

• after touching a patient

• after touching patient surroundings.

The need for effective and appropriate hand hygiene has also been

included in all the care bundles/HIIs (see above).

However, in one area of infection

prevention and control, hand hygiene with alcohol hand rubs does not replace

the absolute requirement for hand washing: this is in relation to diarrhoeal

infections caused by norovirus or Cl. difficile. Alcohol

is not effective against norovirus or against the spores of Cl. difficile, so for these common diarrhoeal infections,

hand washing is essential before and after each patient contact or contact with

the environment around infective patients.

The audit of hand hygiene (alcohol hand rub and hand washing) is an

important part of monitoring compliance with clinical protocols for infection

prevention and control and should include direct observation of all grades of

healthcare staff and also measurement of the volume of alcohol hand rub and

liquid soaps used as a general proxy measurement of hand hygiene practice.

Environmental Cleanliness And Disinfection

Whenever there are problems or outbreaks

of HCAI, there is popular outcry over dirty hospitals, giving the impression

that environmental cleanliness equates to prevention of infection. Whereas

there is no question that hospitals and other healthcare premises should be clean

and that a clean environment promotes good healthcare practice, there is less

of a direct correlation between general cleanliness and rates of HCAI. However,

there is good evidence that bacteria and viruses from infected patients

contaminate the general environment around those patients from where they can

be picked up, e.g. on the hands, by other vulnerable patients or by healthcare

workers and transmitted to other patients. The evidence is particularly clear

with C. difficile spores, which can be found on all

environmental services in rooms where there are patients with CDI. They are particularly

prevalent around toilets, or on commodes, or near bed pan washers.

General hospital cleaning is based on a

detergent and water cleaning regimen, but when there are patients with known

HCAIs, it is advisable to supplement detergent cleaning with use of

environmental disinfectants. This is particularly the case in outbreaks of

norovirus or CDI. The most effective disinfectants for these viruses and for

the spores of Cl. difficile are those based

on chlorine-releasing agents. These should be used routinely in areas where

there are cases of norovirus or CDI.

Antibiotic Prescribing

Good antibiotic stewardship and the prudent

use of these valuable drugs is an important part of the prevention and control

of HCAI. Most bacterial HCAIs are caused by antibiotic-resistant organisms that

flourish under the selective pressure of antibiotic use, and because of the

fact that many of the bacteria are resistant to several different types of

antibiotic, even the use of individual antibiotics can select for bacteria

resistant to a wide range of agents. Furthermore, many of the resistance genes

are carried on transferable genetic elements that can transfer among bacterial

populations, particularly in a selective environment such as a hospital. There

are many examples of links between use of particular antibiotics and cases of

HCAI caused by resistant organisms. There are also more general links between

use of agents such as the fluoroquinolone antibiotics and the rising incidence

of MRSA colonization and infection. With CDI, the link is even more direct with

the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics being a key precipitating factor for this

disease. Outbreaks of CDI have been linked to widespread use of cephalosporins

and, more recently, fluoroquinolone antibiotics when the Cl. difficile strains such as ribotype 027 have

been specifically resistant to these agents.

All healthcare organizations should have antibiotic prescribing

protocols to promote and audit good stewardship. This is a requirement of the

statutory Code of Practice in England. The guidance in the ‘Saving Lives’

package recommends that antibiotic stewardship programme should have the

following elements:

• a prescribing and management policy for antimicrobials

• a strategy for implementing the policy

• an antimicrobial formulary and guidelines for antimicrobial treatment

and prophylaxis

• decision to prescribe should be clinically justified and recorded

• intravenous therapy should only be used for severe infections or where

oral antimicrobials are not appropriate

• intravenous antimicrobials should only be used for 2 days before

review and switch to an oral agent where possible and appropriate

• all antimicrobial prescriptions should include a stop date—generally a

maximum of 5–7 days without represcription

• daily review of antimicrobial treatment

• antimicrobial treatment reviewed on the basis of microbiological

results

• minimize the use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials

• a single dose at induction of anaesthesia for most operations where

antimicrobial prophylaxis is indicated

• training in implementing antimicrobial prescribing guidance for all

prescribers

Training And Education

The implementation of the range of infection prevention and control

practices in any health or social care setting can only be successful if there

is a comprehensive approach to staff education and training through which all

can learn that everyone has a role to play in preventing HCAI. Basic training

in infection prevention and control is mandatory for all staff in many hospitals

and healthcare settings in the UK, Europe and North America, usually with

regular (generally annual) required updates and specialist training for

particular professional groups. Completion of this training is generally a

requirement for successful appraisal and performance review for all staff.

Audit

Whereas surveillance of key HCAIs is necessary for monitoring the changing

pattern and the incidence of infections, audit of implementation of clinical

protocols is equally necessary for maintaining a high level of infection

prevention and control practice. There should be regular audits of hand hygiene

compliance, adherence to antibiotic prescribing guidelines and the implementation

of the clinical protocols in the care bundles/HIIs. The results of these audits

should be reviewed in a timely manner at all levels of management in the health

and social care organizations so that those implementing the protocols have

ownership of the procedures and their effective application. Performance

management at all levels depends upon a combination of the data from

surveillance of the infections and audit of the clinical practice.

Related Topics