Scale of the HCAI Problem-Prevalence and Incidence

| Home | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology |Chapter: Pharmaceutical Microbiology : Public Health Microbiology: Infection Prevention And Control

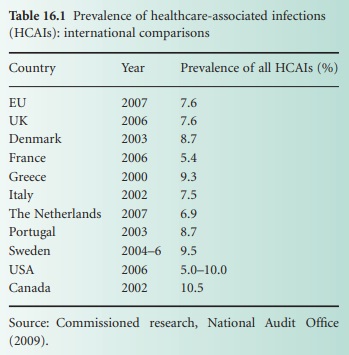

An assessment of the number of cases of HCAI and the risk of infection for different patient groups is based on a series of different measurements. Point prevalence studies have been undertaken in many countries to give a snapshot of the number, and the percentage, of patients with any type of HCAI in a particular healthcare setting on a specific day.

SCALE OF THE HCAI PROBLEM—PREVALENCE AND INCIDENCE

An assessment of the number of cases of

HCAI and the risk of infection for different patient groups is based on a

series of different measurements. Point prevalence studies have been undertaken

in many countries to give a snapshot of the number, and the percentage, of

patients with any type of HCAI in a particular healthcare setting on a specific

day. Prevalence studies in various developed countries over the last decade

have shown overall prevalence rates between 5% and 10% (Table 16.1). A

prevalence study in the four UK countries and the Republic of Ireland in 2006

showed an overall prevalence of 7.6%, ranging from 4.9% in the Republic of

Ireland to 8.2% in England. The low rates in the Republic of Ireland probably

reflected a rather younger patient population overall and the higher number in

England was linked almost entirely to much higher numbers of cases of CDI (2006

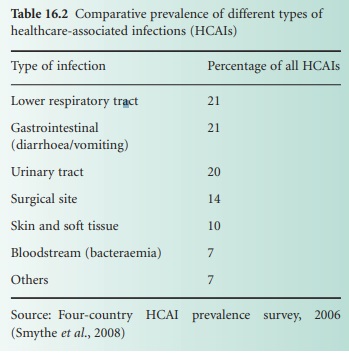

was the height of the epidemic of CDI in hospitals in England). The commonest

types of infection were urinary tract infection, followed by skin and soft

tissue infections and wound infections, respiratory infections, and gastro-intestinal

infections (Table 16.2).

Bloodstream infections accounted for only 7% of HCAIs but represent the most

severe end of the spectrum of disease. MRSA infections of all types accounted

for 16% of the HCAIs and CDI was 17% of the total in hospitals in England but

only 5% in Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Prevalence studies provide valuable

comparisons between hospitals and countries and show the general contribution

of the various types of HCAI. However, they do not represent the actual number

of cases of different HCAIs over time, i.e. the incidence of infection in

different hospitals, wards or patient groups. For example, a point prevalence

of 8.2% does not mean that 8.2% of the patients admitted to the hospitals in

England developed an HCAI because the infected patients tend to be more

seriously ill and have longer stays in hospital both from their underlying

illness and as a result of their HCAI; therefore, the incidence is always less

than the point prevalence. Incidence is measured by ongoing and continued

surveillance of specific infections in which all cases of the infection are

recorded and related to the number of patients at risk. The HCAIs that are most

commonly subject to surveillance programmes are bacteraemias (bloodstream infections)

caused by specific healthcare-associated pathogens such as MRSA or

ESBL-producing E. coli (because they

represent the most severe types of HCAI), SSIs (one of the key indicators of

the quality of a surgical service or an individual surgeon), and CDI.

Surveillance data are necessary for monitoring infection prevention and control

activities at national and regional level, which can provide useful comparisons

between hospitals for patients who may choose where they wish to have their treatment.

However, surveillance with timely feedback and data is particularly important

at local level, within individual hospitals to ensure delivery of a high quality

of care. Most surveillance programmes have depended on voluntary reporting of

the infections to regional or national programmes but in several countries some

high-profilveillance programmes have been made mandatory to ensure that

infection prevention and control is made a high priority for health service

managers and clinicians alike. Mandatory surveillance of MRSA bacteraemia was

introduced in England in 2001, followed CDI, glycopeptide-resistant enterococcal

bacteraemia and SSIs in orthopaedic surgery in 2004. Similar approaches have

been applied in other UK countries, the Republic of Ireland, European countries

and the USA (mostly at an individual state level).

A further development of basic surveillance (i.e. reporting numbers of

cases) is the application of enhanced surveillance in which information about

patient demographics, risk factors, and outcomes is included. This can then be

linked to root cause analysis of individual cases to provide valuable

information about target areas for preventive measures.

What Has Surveillance Told Us?

Mandatory surveillance of MRSA bacteraemia in England showed a steady

rise in cases to a peak of 7700 in 2004. Public and political concern about

MRSA resulted in the government setting a target for a 50% reduction in MRSA

bacteraemia over the 3 years 2005–2008. The surveillance data enabled active

performance management through all levels of the (national) health service,

provided pressures for improved infection prevention and control actions, and

showed show the target was being achieved. Information from enhanced surveillance

within this programme showed the importance of patients’ ages and underlying

conditions as particular risk factors, and most significantly showed the

importance of intravenous catheters and cannulae, renal dialysis catheters,

urinary catheters and chronic wounds and ulcers as sites of MRSA infection

leading to bacteraemia.

A similar approach was taken with CDI when mandatory surveillance showed

that there were 55 000 cases in patients over 65 years of age in England in

2006; as these represent about 75% of cases, this means that there were around

70 000 cases overall. Guidance on prevention and control measures (based on the

1994 guidance) and a target to reduce the number of cases by 30% by 2011

focused activities in NHS hospitals and the 30% reduction was achieved within

the first year (2008–2009).

SSI surveillance in orthopaedic surgery has been a national requirement

in all UK countries for several years. This is a type of surgery with relatively

low rates of infection (<5%) but surveillance has focused attention on infective

complications, shown differences between surgical procedures, and also shown a

steady improvement in rates in all the countries. However, the very short

length of stay now usual for patients after these operations means that some

infections only manifest themselves when the patient is at home. This has shown

the need for including some system of post discharge surveillance for surgical

site infection to give a realistic picture of these HCAIs. This approach is

being pioneered in the UK and the Republic of Ireland in relation to infections

following caesarean section births where there is a clear opportunity for

professional input to post-discharge surveillance because the mothers are seen

at home by a midwife or health visitor.

The HCAI Challenge

The surveillance programmes in various countries have shown the scale of

the challenge set by HCAI in modern health and social care services. Why has

this situation developed? There is a strong argument that during the last quarter

of the 20th century, infections (including HCAI) had not been regarded as an

important part of modern medical practice. There had been a view from the late

1960s onwards that infectious diseases had been conquered and that antibiotics

and vaccines provided the answer. The importance of infection prevention and

control measures was not given its former position in clinical training of

doctors and nurses. Modern medicine was making tremendous progress in the

treatment of malignant diseases, cardiovascular disease, transplantation, and

chemotherapy, and in the management of chronic diseases. Life expectancy

increased markedly and the proportion of very elderly people in the population,

with their inevitable healthcare needs, rose rapidly. This created a vulnerable

patient population at high risk of infection, but these infections were

regarded as incidental nuisances rather than the major risk to a patients’

health and potential mortality which they are. Infections were regarded as the

province of the infection specialists (medical microbiologists, infection

control nurses) who had plenty of interesting work to do but a generally low

profile. The situation changed with the advent of the 21st century and the

recognition of the human and financial costs of HCAIs in a modern healthcare

service.

Related Topics