Sources and Control of Contamination

| Home | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology |Chapter: Pharmaceutical Microbiology : Microbial Spoilage, Infection Risk And Contamination Control

Regardless of whether manufacture takes place in industry or on a smaller scale in the hospital pharmacy, the microbiological quality of the finished product will be determined by the formulation components used, the environment in which they are manufactured and the manufacturing process itself.

SOURCES AND CONTROL OF CONTAMINATION

A) In Manufacture

Regardless of whether manufacture takes place in industry or on a

smaller scale in the hospital pharmacy, the microbiological quality of the

finished product will be determined by the formulation components used, the

environment in which they are manufactured and the manufacturing process itself.

Quality must be built into the product at all stages of the process and not

simply inspected at the end of manufacture:

• Raw materials, particularly water and those of natural origin, must be

of a high microbiological standard.

• All processing equipment should be subject to planned preventive

maintenance and should be properly cleaned after use to prevent

cross-contamination between batches.

• Cleaning equipment should be appropriate for the task in hand and

should be thoroughly cleaned and properly maintained.

• Manufacture should take place in suitable premises, supplied with

filtered air, for which the environmental requirements vary according to the

type of product being made.

• Staff involved in manufacture should not only have good health but

also a sound knowledge of the importance of personal and production hygiene.

• The end-product requires suitable packaging which will protect it from

contamination during its shelf-life and is itself free from contamination.

a)

Hospital Manufacture

Manufacture in hospital premises raises certain additional problems with

regard to contamination control.

i)

Water

Mains water in hospitals is frequently stored in large roof tanks, some

of which may be relatively inaccessible and poorly maintained. Water for

pharmaceutical manufacture requires some further treatment, usually by

distillation, reverse osmosis or deionization or a combination of these,

depending on the intended use of water. Such processes need careful monitoring,

as does the microbiological quality of the water after treatment. Storage of

water requires particular care, as some Gram-negative opportunist pathogens can

survive on traces of organic matter present in treated water and will readily

multiply to high numbers at room temperature. Water should therefore be stored

at a temperature in excess of 80 °C and circulated in the distribution system

at a flow rate of 1–2 m/s to prevent the build-up of bacterial biofilms in the

piping.

ii)

Environment

The microbial flora of the hospital pharmacy environment is a reflection

of the general hospital environment and the activities undertaken there.

Free-living opportunist pathogens, such as Ps. aeruginosa, can

normally be found in wet sites, such as drains, sinks and taps. Cleaning

equipment, such as mops, buckets, cloths and scrubbing machines, may be

responsible for distributing these organisms around the pharmacy; if stored wet

they provide a convenient niche for microbial growth, resulting in heavy

contamination of equipment. Contamination levels in the production environment

may, however, be minimized by observing good manufacturing practices (GMP), by

installing heating traps in sink U-bends, thus destroying one of the main reservoirs

of contaminants, and by proper maintenance and storage of equipment, including

cleaning equipment. Additionally, cleaning of production units by contractors

should be carried out to a pharmaceutical specification.

iii)

Packaging

Sacking, cardboard, card liners, corks and paper are unsuitable for

packaging pharmaceuticals, as they are heavily contaminated, for example with

bacterial or fungal spores. These have now been replaced by nonbiodegradable

plastic materials. In the past, packaging in hospitals was frequently reused

for economic reasons. Large numbers of containers may be returned to the

pharmacy, bringing with them microbial contaminants introduced during use in

the wards. Particular problems have been encountered with disinfectant solutions

where residues of old stock have been ‘topped up’ with fresh supplies,

resulting in the issue of contaminated solutions to wards. Reusable containers

must therefore be thoroughly washed and dried, and never refilled directly.

Another common practice in hospitals is the repackaging of products

purchased in bulk into smaller containers. Increased handling of the product

inevitably increases the risk of contamination, as shown by one survey when

hospital-repacked items were found to be contaminated twice as often as those

in the original pack (Public Health Laboratory Service Report, 1971).

B) In Use

Pharmaceutical manufacturers may justly argue that their responsibility

ends with the supply of a well-preserved product of high microbiological

standard in a suitable pack and that the subsequent use, or indeed abuse, of

the product is of little concern to them. Although much less is known about how

products become contaminated during use, their continued use in a contaminated

state is clearly undesirable, particularly in hospitals where it could result

in the spread of cross-infection. All multidose products are vulnerable to

contamination during use. Regardless of whether products are used in hospital

or in the community environment, the sources of contamination are the same, but

opportunities for observing it are greater in the former. Although the risk of

contamination during product use has been much reduced in recent years,

primarily through improvements in packaging and changes in nursing practices,

it is nevertheless salutary to reflect upon past reported case histories.

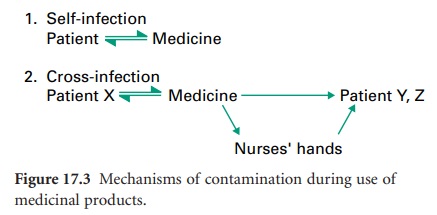

b) Human Sources

During normal usage, patients may contaminate their medicine with their

own microbial flora; subsequent use of such products may or may not result in

self-infection (Figure 17.3).

Topical products are considered to be most

at risk, as the

product will probably

be applied by hand, thus

introducing contaminants from

the resident skin

flora of staphylococci, Micrococcus spp.

and diphtheroids but also

perhaps transient

contaminants, such as Pseudomonas or coliforms, which would normally

be removed with effective hand-washing. Opportunities for contamination may be reduced

by using disposable applicators for topical products or by giving

oral products by disposable

spoon.

In hospitals, multidose

products, once contaminated, may serve as a vehicle

of cross-contamination or cross-infection between patients. Zinc-based products

packed in large stockpots and used in the treatment

and prevention of bedsores in long-stay and geriatric patients were reportedly contaminated during use with Ps. aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. If unpreserved, these products

permit multiplication of contaminants, especially if water is present either

as part of the formulation, for example in oil/water (o/w) emulsions, or as a film in w/o emulsions

which have undergone local

cracking, or as a condensed film from atmospheric water. Appreciable numbers of contaminants may then be transferred to other patients when the product is reused. Clearly

the economics and convenience of using stockpots need to be balanced against

the risk of spreading cross-infection between patients and the inevitable increase in length of the patients’ stay in hospital. The use of stockpots

in hospitals

has noticeably declined

over the past two

decades or so.

A further

potential source of contamination in hospitals is the nursing staff responsible for medicament

administration. During

the course of their work, nurses’ hands become contaminated with opportunist pathogens which are not

part of the normal skin

flora but which

are easily removed

by thorough hand-washing and drying. In busy

wards, hand-washing between

attending to patients may be overlooked and

contaminants may subsequently be transferred to medicaments during administration.

Hand lotions and creams used to prevent

chapping of nurses’ hands may similarly become

contaminated, especially when packaged

in multidose containers and left at the side of the hand-basin, frequently without lids.

Hand lotions and creams should be well preserved

and, ideally, packaged in disposable dispensers. Other effective control methods include the supply of products in individual patient’s

packs and the use of non-touch techniques for medicament administration. The importance of thorough hand-washing in the control

of hospital cross-infection cannot be overemphasized. In recent

years hospitals have successfully raised

the level of awareness

on this

topic among staff

and the general

public through widespread publicity and the provision of

easily accessible hand disinfection stations

on the wards.

c)

Environmental Sources

Small numbers

of airborne contaminants may settle in products left open to the atmosphere. Some of these

will die during storage, with the rest

probably remaining at a

static level of about 102–103 colony

forming units (CFU) per gram or per millilitre. Larger

numbers of waterborne contaminants

may be accidentally introduced into topical

products by wet hands

or by a ‘splash-back mechanism’ if left at the side of a basin.

Such contaminants generally have simple nutritional

requirements and, following multiplication, levels of contamination may often exceed 106 CFU/g.

In the past this problem

has been encountered particularly

when the product

was stored in warm hospital wards or in hot steamy bathroom

cupboards at home. Products used in hospitals

as soap substitutes for

bathing patients are particularly at risk and soon not only

become contaminated with opportunist pathogens such as Pseudomonas spp.,

but also provide

conditions conducive to their

multiplication. The problem

is compounded by stocks kept

in multidose pots

for use by several patients in the same ward over an extended

period of time.

The indigenous microbial population is quite different in the home

and in hospitals. Pathogenic organisms are found much more

frequently in the latter and

consequently are isolated more often from medicines used in

hospital. Usually, there are fewer opportunities for contamination in the home, as patients are generally issued with individual supplies in small quantities.

d) Equipment Sources

Patients and nursing staff may use a range of applicators (pads, sponges, brushes

and spatulas) during

medicament administration, particularly for topical products. If reused, these easily become contaminated and may be responsible for perpetuating contamination

between fresh

stocks of product, as has indeed been

shown in studies of

cosmetic products. Disposable applicators or swabs should therefore

always be used.

In hospitals today a wide

variety of complex

equipment is used in the course of patient treatment. Humidifiers, incubators, ventilators,

resuscitators and other apparatus require

proper maintenance and decontamination after

use. Chemical disinfectants used for this purpose have in the past,

through misuse, become

contaminated with opportunist pathogens, such as Ps. aeruginosa, and ironically have contributed to, rather than

reduced, the spread of cross-infection in hospital patients. Disinfectants should only be used for their

intended purpose and directions for use must be followed

at all times.

Related Topics