Characteristics of General Practice Research Database 2005

| Home | | Pharmacovigilance |Chapter: Pharmacovigilance: The General Practice Research Database

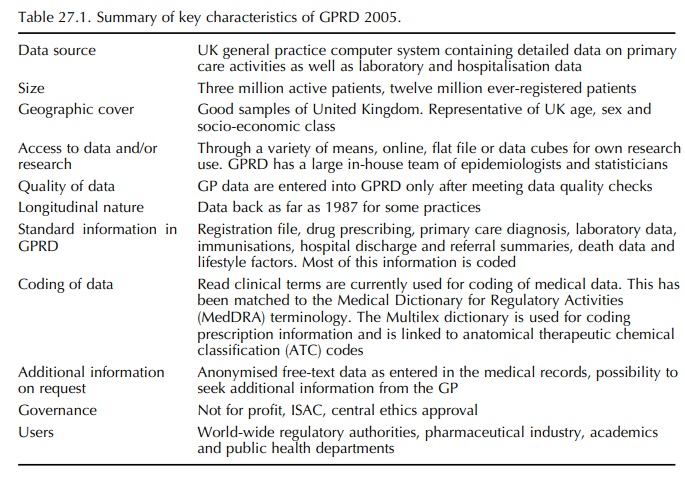

lists the main characteristics of the GPRD in 2005. It should be recognised that GPs use their computers primarily to create electronic medical records for the purpose of managing their patients.

CHARACTERISTICS OF GENERAL

PRACTICE RESEARCH DATABASE 2005

Table 27.1 lists the main characteristics of the GPRD in 2005. It should be recognised that GPs use their computers primarily to create electronic medical records for the purpose of managing their patients. However, contributing GPs are provided with record-ing guidelines that define what information should be recorded electronically so making the research under-taken in GPRD more valid:

• Demographics, including the patient’s age and

sex.

• Medical diagnosis, including free-text

comments.

• All prescriptions and immunisations as given

in primary care.

• Referrals to hospitals or specialists.

• Laboratory results, including microbiology.

• Treatment outcomes, including hospital

discharge reports where patients are referred to hospital for treatment.

• Key patient information, e.g. smoking status,

height and weight.

• Date and cause of death.

• Pregnancy-related information.

Following receipt and processing of a data collec-tion, the GPRD Group provide feedback reports to the contributing practice on the completeness of data in key areas (e.g. date and cause of death and patient registration details), to enable practices to address any deficiencies they have with their recording. In addi-tion, the quality of recording across the entirety of data contributed by a practice is assessed by means of the ‘up to standard’ audit that assesses the complete-ness, continuity and plausibility of data recording in key areas, in accordance with the recording guide-lines issued to practices. Where data quality is found to be acceptable, the practice is judged to be ‘up to standard’ and marked as such in the database; this marker can be used to identify those practices where data recording is considered by the GPRD Group to be of sufficient quality for research purposes.

In

April 2004, the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF) was introduced into UK general

practice. This framework provides incentives to practices for the provision of

high quality care that naturally involves improved data documentation. Data

from the prac-tice records are submitted to and analysed by the Quality

Management and Analysis System (QMAS), a national IT system, that supports the

QOF payment process. Achievement is measured against indica-tors in four

domains; most importantly, the clinical domain, which focuses on a range of

indicators in 11 key disease areas. Given the key role of practice records in

supplying the data needed to assess prac-tice achievement/performance, there is

now even more emphasis for practices to ensure that their records are complete,

particularly in areas related to QOF indica-tors. This can only be of benefit

to research.

The

GPRD is a unique public health research tool, which has been used widely for

drug safety stud-ies and many other types of pharmacoepidemiolog-ical research.

There are now over 500 GPRD-based peer-reviewed publications, nearly 2000

peer-review impact points and an ever expanding international user base.

Numerous independent validation studies have confirmed a high level of

completeness and validity of the data in the GPRD. A large study recently

examined the validity of the computerized diagnoses of autism in the GPRD.

Anonymised copies of all relevant avail-able clinical reports, including GP’s

notes, consultant, speech therapy and educational psychologists reports, were

evaluated for 318 subjects with a diagnosis of autism recorded in their

electronic general prac-tice record. For 294 subjects (92.5%), the diagnosis of

pervasive developmental disorder was confirmed after review of the records, providing

evidence that the positive predictive value of a coded diagnosis of autism

recorded in the GPRD is high (Fombonne et

al., 2004). Another study compared the distribution of the cause of death in GPRD to national mortality statistics and

concluded that they were broadly simi-lar. This provides further evidence that

the GPRD population is broadly representative of the general population (Shah

and Martinez, 2004).

Recent

research includes a case-series analysis of the risks of myocardial infarction

and stroke after common vaccinations and naturally occurring infec-tions. It

found that there was no increase in the risk of myocardial infarction or stroke

in the period after influenza, tetanus or pneumococcal vaccination. However,

the risks of both events were substantially higher after a diagnosis of

systemic respiratory tract infection and were highest during the first 3 days,

suggesting that acute infections are associated with a transient increase in

the risk of vascular events (Smeeth et al.,

2004). A study by Martinez compared the risk of non-fatal self-harm and suicide

in patients n taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) with that

of patients taking tricyclic antidepressants. No evidence was found that the

risk of suicide or non-fatal self-harm in adults prescribed SSRIs was greater

than in those prescribed tricyclic antidepres-sants (Martinez et al., 2005).

Most

of the drug safety research in the GPRD has concerned the estimation of

relative rates, i.e. the rate of outcomes in exposed patients divided by that

in control patients. But relative rates do not convey the public health

importance of a safety issue. Large rela-tive rates for rare events may not be

of major concern, whereas small relative rates for frequent events may

potentially have large implications. An example for this may be the

cardiovascular risk of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, which may have

affected a large number of patients. Recent research developed methods to

estimate, in the GPRD, individual long-term probabilities specific for a

patient’s age, sex and clinical characteristics. This was done for estimating

the long-term risk of fracture in patients using oral glucocorticoids. As an

example, it was found that a woman aged 65 years with rheumatoid arthritis, low

body mass index (BMI) and a previous history of frac-ture and falls, who used

15 mg glucocorticoids daily, would have a 5-year fracture risk of 47% (a man

with similar history, 30.1%) (van Staa et

al., 2005). This approach to quantify individualised long-term

probabilities can help to better quantify the risks and benefits associated

with a treatment.

Related Topics