Current systems

| Home | | Hospital pharmacy |Chapter: Hospital pharmacy : Medicines supply and automation

In recognising that many processes had changed little since the 1970s and 1980s, a number of factors have influenced the systems and processes for the supply of medicines in UK hospitals over the past decade.

Current systems

In recognising that

many processes had changed little since the 1970s and 1980s, a number of

factors have influenced the systems and processes for the supply of medicines

in UK hospitals over the past decade. Hospitals have a much higher occupancy

rate, with reduced lengths of stay. There has been an increased emphasis on

clinical governance and growing awareness of medication errors. Patients have

more chronic illnesses and complex medication regimens. The European Community

Directive 92/27 was incorporated into UK law on 1 January 1999. It required,

amongst other things, that all medicines supplied to patients should include a

patient information leaflet (PIL) and be labelled with the product batch number

and expiry date. The directive was one of the key drivers behind the

introduction of original pack dispensing into hospital practice. Traditional

practice of limiting discharge supplies and split-ting packs risked non-compliance

with the law and possible prosecution.

Along with

individual patient dispensing and the more recent models of supply, the use of

patient bedside medicine cabinets is now widely adopted as an established

practice across the NHS. The benefits of the cabinets are that individual

patients’ medicines are kept at their bedside, reducing the risk of selection

errors and errors of omission and, in addition, the traditional nursing drug

trolley, which was traditionally crammed with a huge array of medicines, is now

a much more streamlined operation which also has the benefit of reducing

selection error.

It is perhaps

helpful to mention the arrangements under which hospital pharmacies operate at

this point. Unlike community pharmacies, hospital pharmacy departments do not

require premises registration with the General Pharmaceutical Council to

provide services to their wards and out-patients. Whilst at the time of writing

the Medicines Act is under review, the current exemption is based on section 10

of the Act and relates to a ‘hospital’s normal business’. Hospital pharmacies

do have quality systems and detailed standard operating procedures for

dispensing and supply just as required for registered pharmacies. However, many

hospital pharmacies do register: this became common when Crown immunity was

removed over 20 years ago. This permits them to undertake other activities not

‘normal business of a hospital’ and where this is the case the responsible

pharmacist requirements apply. A detailed discussion of this is beyond the

remit of this chapter. Details about responsible pharmacist can be found on the

General Pharmaceutical Council website at

http://www.pharmacyregulation.org/regulatingpharmacy/thepharmacyregister/responsiblepharmacist/index.aspx.

Non-stock dispensing

The choice of

inpatient supply system for a hospital lies anywhere on a spectrum between

total stock and almost complete individual dispensing. Whilst the former was

the traditional Scottish system and the latter is favoured in private hospitals

because it facilitates charging, the choice in NHS hospitals throughout the UK

should now be based on a careful risk appraisal of the options and resources

(principally staff) available.

'One-stop dispensing'

Original pack

dispensing has now been widely adopted across most hospitals in the UK and is

referred to as ‘one-stop dispensing’ or ‘dispensing for discharge’. The concept

is to combine inpatient and discharge dispensing into a single supply, labelled

with directions for use. In this system, patients’ medicines are supplied as

soon as they are needed, and labelled for discharge so that only one supply is

made during the patient’s stay. Manufacturers’ original packs are usually

dispensed and the patient is discharged with what remains after use in

hospital. If this is less than a minimum quantity agreed with local general

practitioners (GPs), usually 2 weeks’ supply, an additional pack is issued.

Large numbers of individually dispensed items cannot be handled in a

conven-tional medicines trolley, so each patient normally has a bedside

medicines cabinet, which can also be used for the patient’s own drugs (PODs:

see later in chapter) or in a self-administration scheme. To operate

efficiently, a judge-ment needs to be made about which medicines can be

relabelled for discharge early in the patient’s admission, and which cannot.

For example, aspirin 75 mg tablets for cardiovascular disease are almost

universally prescribed and taken by patients as a once-daily dose and,

similarly, statins are also taken once at night. Therefore it would be

reasonably safe to make the assumption that, provided the patient continues to

take the medicine after discharge, the directions will probably not change.

However, in the case of warfarin, corti-costeroids or antibiotics, for example,

it is likely that doses or duration of treatment will change before or at the

point of discharge, such that labelling them before this point is somewhat

risky. These also reduce the risk of medi-cation error by limiting the choices

for selection at administration times and allow nurses to give more

individualised patient care. There is a need to keep the contents of cabinets

up to date with prescription changes and, at discharge, to check that the pack

quantity and label are still appropriate and that the cabinet is empty, all of

which may be undertaken by a pharmacist or technician.

Patients benefit by

having PILs provided and by avoiding the wait for discharge medicines to be

dispensed, provided that the prescription is written in good time, and also by

having more time before ordering repeat prescrip-tions. The hospital can meet

its legal obligation on PILs and also benefits from speedier discharges.

The Royal

Pharmaceutical Society’s Hospital Pharmacists Group has pro-duced useful guidance

on the introduction of one-stop dispensing, use of PODs and self-administration

schemes. Using patient packs at the time of discharge, a possible intermediate

step to one-stop dispensing, has also been successful.

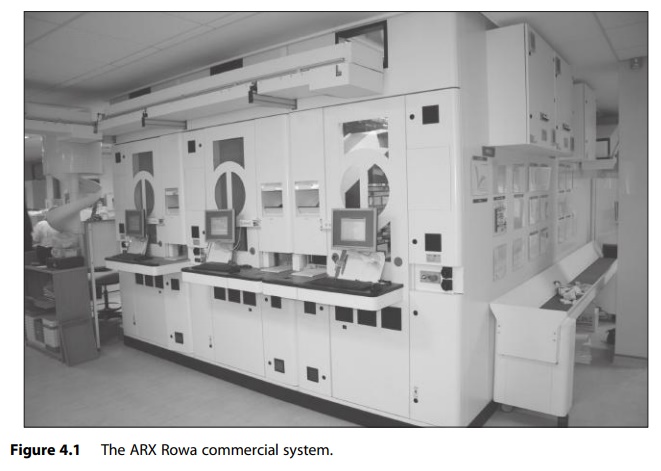

The review of

medicines management in NHS hospitals undertaken by the Audit Commission in

2001 and the recommendations made have had a pro-found impact on the

modernisation of the dispensing process. Many NHS hospitals have installed

automated dispensing systems in the past decade as a consequence of the

recommendations. A number of commercial systems are now available that

accurately pick original patient packs to support the one-stop dispensing

process and support re-engineering of services. Figure 4.1 provides an example

of such a system the ARX Rowa from the Countess of Chester NHS Foundation

Trust.

Scanning of bar

codes is also used in loading such machines, enabling the robot to identify

different products, strengths or pack sizes. Products can be packed very

compactly because any gaps can be filled without regard to any human need for

selection, as positions are memorised by the system’s com-puter. The machines

can also occupy less floor space than an equivalent amount of conventional

shelving. A number of studies have shown the bene-ficial impact on dispensing

errors, reduced dispensary turnaround times, simplified ordering systems,

improved reliability of service and more efficient use of staff.

Patients' own drugs

Patients admitted to

hospital are usually asked to bring their medicines with them to facilitate the

recording of their drug history and some trusts run publicity campaigns on bus

adverts and in GP practices to promote this. Traditionally, PODs were routinely

returned to pharmacy for destruction once a hospital supply was obtained.

However, the move to dispensing of prescriptions in primary care using

manufacturers’ original packs has given much greater confidence in their

continued usefulness, but only for the patient to whom they were originally

supplied. Before use their suitability must be assessed, with this being

variously undertaken by pharmacists, technicians, doctors or nurses at

different hospitals. Most hospitals will have a policy or set of procedures

covering this. Reuse of patients’ own medicines has a number of benefits,

including the reduced risk of medication errors, since PODs can be used a

reference to patients’ medicines consumption prior to admission.

When the directions

are inappropriate, relabelling by pharmacy staff may be permissible. As with

one-stop dispensing, further checks on directions and quantities are required

on discharge. The importance of these, including the check that the locker has

been emptied, has been shown by reported errors, which also highlight the need

for thorough training of those involved. Guidance on implementation includes

the need for publicity to encourage patients to bring in their medicines.

Unit dose systems

Unit dose systems

have been adopted quite widely in North America and many European countries but

have only been tried to a limited extent in the UK. The concept is that

pharmacy provides medicines to wards in single-unit packages, either just prior

to the time of administration or on a daily or (for long-stay) weekly basis,

placing them in the patient’s individually labelled drawer in a medicine

cabinet, trolley or cassette. Because of the labour-intensive nature of this

work, and the advent of original pack dispensing, it has not been widely adopted

in the UK.

Related Topics