Oestrogen and Venous Thromboembolism

| Home | | Pharmacovigilance |Chapter: Pharmacovigilance: The Cardiovascular Spectrum of Adverse Drug Reactions

Identification and confirmation of the adverse effects of postmenopausal hormone therapy illustrate yet a third approach to risk assessment. Oestrogen has been used to treat menopausal symptoms since 1933 when emmenin was introduced.

OESTROGEN AND VENOUS

THROMBOEMBOLISM

Identification

and confirmation of the adverse effects of postmenopausal hormone therapy

illustrate yet a third approach to risk assessment. Oestrogen has been used to

treat menopausal symptoms since 1933 when emmenin was introduced. Premarin, a

more easily manufactured oestrogen, was approved in 1942 (CDER, 1997; FDA,

2003). By the 1960s, 12% of women in the United States were using

post-menopausal oestrogen therapy, a proportion that increased steadily. The

National Prescription Audit and National Disease and Therapeutic Index

databases tracked annual hormone therapy prescriptions rising from 58 million

in 1995 to 90 million in 1999; prescriptions then remained stable through June

2002 (Hersh, Stefanick and Stafford, 2004). Analysis of data from a large

cohort study in the United States showed that 45% of postmenopausal women used

oestrogen for at least a month and more than 20% used it for 5 or more years,

either alone or in combination with progestin (Brett and Madans, 1997).

These

rates have been shown to differ based on a woman’s hysterectomy status; in a

study by Keating and colleagues in the early 1990s, current post-menopausal

hormone use was 58.7% among women with prior hysterectomy compared to 19.6%

among women with intact uteri (Keating, Manassiev and Stevenson, 1999). Most

women started to take ther-apy shortly after menopause; median duration of use

was 3 years (mean 6.6 years). Postmenopausal hormone use demonstrated a secular

trend; only 19% of women born before 1904 ever used postmenopausal hormones,

compared to 63% of women born between 1945 and 1954 (Brett and Madans, 1997).

In

1992, the American College of Physicians recom-mended hormone therapy for

postmenopausal women who either had hysterectomy or were at risk of coronary

heart disease (American College of Physi-cians, 1992). It quickly became

standard medical practice to prescribe exogenous oestrogens, either alone or in

combination with progestin, for most menopausal women, with the expectation that

most, if not all of these women, would benefit from treatment. Initially, most

women received unopposed oestro-gen regardless of their hysterectomy status.

After the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute-funded Post-menopausal

Oestrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) trial reported an increased risk of

endometrial hyper-plasia when women with intact uteri were treated with

unopposed oestrogen in 1995, most women with intact uteri were switched to

combination oestrogen– progestin therapy (The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial,

1996). Indeed, when the Women’s Health Initia-tive was being planned in the

early 1990s, there was debate about the ethics of withholding post-menopausal

hormone therapy from the women who would be randomized to placebo.

A

cloud was introduced to that climate of enthu-siasm for oestrogen in the 1960s

when an apparent increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), that is, deep

venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, was associated with oral

contraceptive use (Royal College of General Practitioners, 1967; Vessey and

Doll, 1968, 1969; Jick et al., 1995;

Spitzer, 1997).

The

relationship between VTE and exogenous oestro-gen was explored in several small

case-control and cohort studies in the 1970s (BCDSP, 1974; Nachtigall et al., 1979; Petitti et al., 1979). In these analyses, VTE was more common in women taking

oral contra-ceptives, but the relationship with postmenopausal hormone therapy

was less clear. These epidemiologic studies were followed by large randomized,

controlled trials.

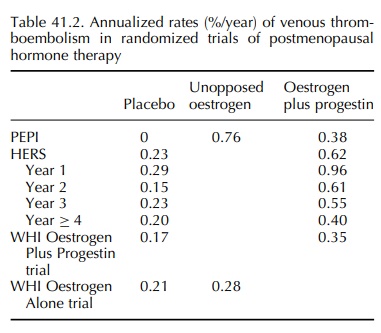

The

PEPI was a 3-year randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 875 postmenopausal

women comparing the effects of several postmenopausal hormone regimens on

cardiovascular disease risk factors. The cohort was healthy and relatively

young; consequently, only ten VTE cases were identified among women on active

hormone therapy and none on placebo during the 3-year follow-up (The Writing

Group for the PEPI Trial, 1995). The rate of VTE in women taking conjugated

oestrogens (0.625 mg daily) alone was twice that of women taking any of three

oestrogen plus progestin regimens (Table 41.2), but the overall number of cases

was small.

The

Heart & Oestrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) randomized 2763 women

with hormone therapy increased VTE risk (relative hazard 2.7, 95% confidence

interval 1.4–5.0); the rela-tive hazard for deep venous thrombosis was 2.8 (95%

confidence interval 1.3–6.0) and for pulmonary embolism was 2.8 (95% confidence

interval 0.9–8.7) with oestrogen plus progestin.

The

Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) includes two randomized, placebo-controlled

hormone trials, one with unopposed conjugated oestrogens (0.625 mg daily) in 10

739 women with prior hysterectomy, and the other with conjugated oestrogens

0.625 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5 mg daily in 16 608 women with

intact uteri. In the trial of unopposed oestrogen, the hazard ratio for VTE was

1.33 (95% confidence interval 0.99–1.79) (WHI Writing Group, 2004). In the

trial of combination oestrogen plus progestin, the hazard ratio for VTE was

2.06 (95% confidence interval 1.57–2.70) (Cushman et al., 2004). In these predominantly healthy women, the annualized

rates of VTE were lower than in HERS (Table 41.2), but the studies demonstrated

a similar pattern of risk by year of treatment. In the WHI Oestrogen Plus

Progestin trial, the yearly hazard ratios were 4.01 in year 1, 1.97 in year 2,

1.74 in year 3, 1.70 in year 4, 2.90 in year 5 and 1.04 in year 6 or later.

In

a Bayesian meta-analysis which included PEPI and HERS, but not the WHI, the

overall relative risk of VTE with postmenopausal hormone therapy was 2.14 (95%

credible interval 1.64–2.81) (Miller, Chan and Nelson, 2002). This

meta-analysis also supported the observation in HERS that the greatest risk for

thromboembolic events with oestrogen was during the first year (relative risk

3.49, 95% credible interval 2.33–5.59).

The

labels for oestrogen formulations have been repeatedly updated to reflect new

findings, including the risk of VTE. A major change was made in 1998, when a

warning was added stating,

In some epidemiological studies,

women on oestro-gen replacement therapy, given alone or in combi-nation with a

progestin, have been reported to have an increased risk of thrombophlebitis,

and/or throm-boembolic disease, although the evidence is conflict-ing In some

epidemiological studies, women on oestrogen replacement therapy, given alone or

in combination with a progestin, have been reported to have an increased risk

of thrombophlebitis, and/or thromboembolic disease, although the evidence is

conflicting (FDA, 1998).

Following

release of the WHI results in 2002, a black box statement pertaining to

cardiovascular risks was added to the label for oestrogen. This state-ment

read, ‘The women’s health initiative (WHI) reported increased risks of

myocardial infarction, stroke, invasive breast cancer, pulmonary emboli, and

deep vein thrombosis in postmenopausal women during 5 years of treatment with

conjugated equine oestrogens (0.625 mg) combined with medroxypro-gesterone

acetate (2.5 mg) relative to placebo.’ The warning goes on to state that the

FDA assumes these findings will hold for all HRT formulations contain-ing

oestrogen and suggests that HRT drugs should be used in the lowest doses

necessary for the shortest duration possible (FDA, 2003).

The

WHI experience altered the way the medical community, lay public and regulatory

agencies viewed the entire issue of drug safety. Awareness of the need for long

term randomized studies of commonly accepted therapies has been enhanced, along

with the importance of ‘real world’ follow-up studies of drugs – many of which

were approved long before current pharmacovigilance guidelines.

Related Topics