Statistical Methods of Evaluating Pharmacovigilance Data

| Home | | Pharmacovigilance |Chapter: Pharmacovigilance: Statistical Methods of Evaluating Pharmacovigilance Data

The three main challenges of pharmacovigilance, that is to detect, to assess and to prevent risks associated with medicines (Bégaud, 2000), may concern both the patient level and the populational level.

Statistical Methods

of Evaluating Pharmacovigilance Data

INTRODUCTION

The

three main challenges of pharmacovigilance, that is to detect, to assess and to

prevent risks associated with medicines (Bégaud, 2000), may concern both the

patient level and the populational level. Similarly, the latter may rely on

classical epidemiological studies, for example cohort or case-control, or on

cases-only anal-yses, which is the scope of spontaneous reporting (SR).

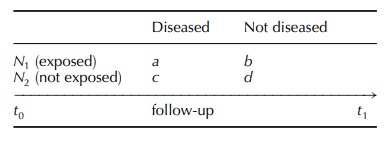

In cohort studies (Kramer, 1988),

subjects are followed in a forward direction from exposure to outcome (e.g. the

occurrence of a given disease), and inferential reasoning is from cause to

effect. For exam-ple, in the case of a cohort study with a reference group, the

subjects can be split, at the end of the follow-up, among the four cells of the

following clas-sical two-by-two table:

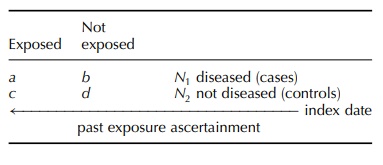

In case–control studies, subjects

are investigated in a backward direction, from outcome (disease) to expo-sure

and inference is from effect to cause:

In

both designs, the compared groups are generally drawn from a larger source

population, which raises the problem of possible selection biases; however, the

subjects are generally exhaustively classified according to a binary variable:

to present or not to present the considered disease in cohort studies, or to

have been or not to have been exposed to the studied factor in case–control

studies. SR, per se, is a passive

surveillance method involving the whole source-population, for example all

subjects of as given country treated with a given medicine; however, SR suffers

two major limitations (Bégaud, 2000):

·

it does not provide any direct and reliable infor-mation on

the size, characteristics and exposure patterns of the source population;

·

the term spontaneous

refers to the random charac-ter of the case collection from the exposed

popu-lation; indeed, reporting assumes that the observer

(i) identifies the adverse event,

(ii) imputes its occurrence to a drug exposure, (iii) is aware of the existence

of a pharmacovigilance system, and (iv) is convinced of the need to report the

case if relevant, for example new and/or serious adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

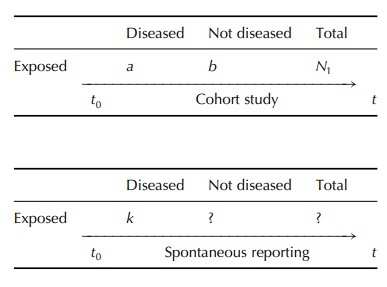

This

results in the major plague of this surveil-lance method: an inescapable under-reporting, the magnitude and

selectivity of which are unknown and extremely difficult to assess. Indeed, if

a number a of cases of a given event have occurred in a population during the

‘follow-up’ period, then it is likely that only a part k = a/U of these cases will be

reported, U being the under-reporting

coefficient varying from 1 to infinity, for example U = 4 if 25% of cases have been

reported.

Moreover,

it is hard to believe that each of the a cases that have occurred have an

identical probability 1/U to be reported. Many factors have been shown to

influence reporting (Pierfitte et al.,

1999) such as the age of the patient, the seriousness of the event and its

onset delay. Thus, because of a selection bias, k could be a non-representative

sample of the source population of cases.

From

a biostatistical point of view, the rather bizzare design of SR could be

compared to a cohort study without reference group in which:

·

the ‘followed’ population is extremely large, that is the

whole population of the surveyed territory treated with drugs;

·

the characteristics of this population, for example age and

gender distributions, concomitant diseases, are unknown as are its

characteristics of exposure (indications, dose, duration, co-medications,

etc.);

·

the number of ‘investigators’ is extremely large, that is

all health professionals in the territory;

·

the case collection does not rely on a precise protocol and

is thus non-systematic and may be subjective.

Moreover, because of the open character

of this method of surveillance (any type of drug, any type of event), there is

in fact a quasi-infinite number of sub-cohorts, one for each type of drug

exposure:

While

the cohort study can estimate the risk associated with a given drug exposure by

calculation of the inci-dence rate a/N1t (number of new occurrences

of the disease produced by the surveyed population during the period t), to

estimate risks from SRs requires rather complex assumptions and calculations.

Related Topics