The Basis of Pharmacovigilance

| Home | | Pharmacovigilance |Chapter: Pharmacovigilance: The Basis of Pharmacovigilance

Pharmacovigilance – the study of the safety of marketed drugs under the practical conditions of clinical use in large communities – involves the para-dox that what is probably the most highly regulated industry in the world is, from time to time, forced to remove approved and licensed products from the market because of clinical toxicity.

THE BASIS OF PHARMACOVIGILANCE

Introduction

‘Not all hazards can be known before a drug is

marketed’.

Committee

on Safety of Drugs, Annual Report 1969, 1970.

Pharmacovigilance

– the study of the safety of marketed drugs under the practical conditions of

clinical use in large communities – involves the para-dox that what is

probably the most highly regulated industry in the world is, from time to time,

forced to remove approved and licensed products from the market because of

clinical toxicity. Why is such close regulation not effective in preventing the

withdrawal of licensed products? The question has been with us from the very

early days of the 1960s and remains with us today, and its consideration tells us

a great deal about pharmacovigilance.

The

greatest of all drug disasters was the thalido-mide tragedy of 1961–62.

Thalidomide had been introduced, and welcomed, as a safe and effective hypnotic

and anti-emetic. It rapidly became popular for the treatment of nausea and

vomiting in early pregnancy. Tragically, the drug proved to be a potent human

teratogen that caused major birth defects in an estimated 10 000 children in

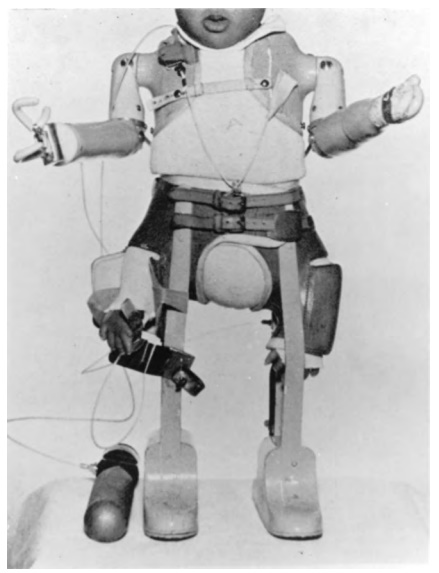

the countries in which it was widely used in pregnant women. Figure 1.1 shows a

child with thalidomide-induced amelia of the upper limbs and phocomelia of the

lower limbs fitted with the kind of prostheses available at that time. The

story of this disaster has been reviewed elsewhere (Mann, 1984).

Figure 1.1. Child with thalidomide-induced deformities of the upper and lower limbs fitted with pneumatic prostheses.

The

thalidomide disaster led, in Europe and else-where, to the establishment of the

drug regulatory mechanisms of today. These mechanisms require that new drugs

shall be licensed by well-established regu-latory authorities before being

introduced into clini-cal use. This, it might be thought, would have made

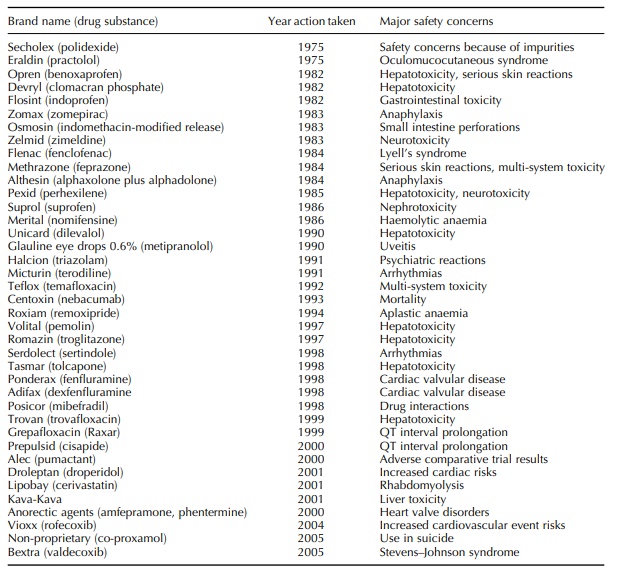

medicines safe – or, at least, acceptably safe. But Table 1.1 summarizes a list

of 39 licensed medicines withdrawn, after marketing, for drug safety reasons

since the mid-1970s in the United Kingdom.

Table 1.1. Drugs withdrawn in the United Kingdom by the marketing authorization holder or suspended or revoked by the Licensing Authority.

Why

should the highly regulated pharmaceutical industry need, or be compelled, to

withdraw licensed medicines for drug safety reasons? Why do these problems of

licensed products being found toxic continue despite the accumulated experience

of more than 45 years since the thalidomide tragedy?

Partly, the problem is one of numbers. For example, the median number of patients contributing data to the clinical safety section of new drug licensing applications in the United Kingdom is only just over 1500 (Rawlins and Jefferys, 1991). Increasing regulatory demands for additional information before approval have presumably increased the average numbers of patients in applications, especially for new chemical entities; nevertheless, the numbers remain far too small to detect uncommon or rare adverse drug reactions (ADRs), even if these are serious.

The

size of the licensing applications for impor-tant new drugs cannot be

materially increased without delaying the marketing of new drugs to an extent

damaging to diseased patients. Thus, because of this problem with numbers, drug

safety depends very largely on the surveillance of medicines once they have

been marketed.

A

second reason for difficulty is that the kinds of patients who receive licensed

medicines are very different from the kinds of volunteers and patients in whom

pre-marketing clinical trials are undertaken. The patients in formal clinical

trials almost always have only one disease being treated with one drug. The

drug, once licensed, is likely to be used in an older group of patients, many

of whom will have more than one disease and be treated by polypharmacy. The

drug may also be used in paediatric patients, who are generally excluded from

initial clinical trials. The formal clinical trials may be a better test of

efficacy than they are of safety under the practical conditions of everyday

clinical usage.

A

third problem is that doctors may be slow or inef-fective in detecting and

reporting adverse drug effects. Many of the drugs summarized in Table 1.1 were

in widespread, long-term use before adverse reactions were detected, and even

now, hospital admissions due to ADRs have shown an incidence of between 2.4%

and 3.6% of all admissions in Australia with simi-lar or greater figures in

France and the United States (Pouyanne et

al., 2000). Even physicians astute in detecting adverse drug effects are

unlikely to identify effects of delayed onset.

A

fourth reason for difficulty is that drugs are often withdrawn from the market

for what may be very rare adverse effects – too infrequent by far to have shown

up in the pre-licensing studies – and we do not yet have effective means in

place for monitoring total post-marketing safety experience. This situation may

well change as large comprehensive databases such as the General Practice

Research Database (GPRD) become more widely used for signal detection and

evaluation. These databases record, in quite large and representative

populations, all usage of many specific medicines and clinical outcomes and can

be used to systematically screen for and evaluate serious adverse events.

Because they contain comprehensive infor-mation on some important information,

such as age, sex, dose and clinical events on all patients in the represented

population, they are systematic compared with spontaneous reporting systems.

They may offer a better chance of detecting long-latency adverse reac-tions,

effects on growth and development and other such forms of adverse experience.

Some

of the difficulties due to numbers, patient populations and so on were

recognized quite early. The Committee on Safety of Drugs in the United Kingdom

(established after the thalidomide disas-ter, originally under the chairmanship

of Sir Derrick Dunlop, to consider drug safety whilst the Medicines Act of 1968

was being written) said – quite remarkably – in its last report (for 1969 and

1970) that ‘no drug which is pharmacologically effective is without hazard.

Furthermore, not all hazards can be known before a drug is marketed’. This then

has been known for over 35 years. Even so, many prescribers still seem to think

that licensed drugs are ‘safe’, and they are surprised when a very small

proportion of licensed drugs have to be withdrawn because of unex-pected drug

toxicity. Patients themselves may have expectations that licensed drugs are

‘completely safe’ rather than having a safety profile that is acceptably safe

in the context of the expected benefit and nature of the underlying health condition.

The

methodological problems have been long recognized. The Committee on Safety of

Medicines, the successor in the United Kingdom to the Dunlop Committee,

investigating this and related problems, established a Working Party on Adverse

Reactions. This group, under the chairmanship of Professor David Grahame-Smith,

published its second report in July 1985. The report supported the continuation

of methods of spontaneous reporting by professionals but recommended that

post-marketing surveillance (PMS) studies should be undertaken on

‘newly-marketed drugs intended for widespread long-term use’; the report also

mentioned record-linkage meth-ods and prescription-based methods of drug safety

surveillance as representing areas of possible progress (Mann, 1987).

Similar

reviews and conclusions have emerged from the United States since the

mid-1970s. A series of events in the United States recently created a

resurgence of interest in drug safety evaluation and management. The

Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) of 1992 provided additional resources at

the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for drug reviews through user fees and

established target time-lines for FDA reviews. The shorter approval times lead

to some medications being approved sooner in the United States than that in

Europe in contrast to the pre-PDUFA experience. A few highly visible drug

withdrawals led to a perception that perhaps drugs were being approved too

quickly. Lazarou, Pomeranz and Corey (1998) published the results of a

meta-analysis that estimated that 106 000 fatal adverse reac-tions occurred in

the United States in 1994. This and other articles (Wood, Stein and Woosley,

1998) stimulated considerable public, congressional and regulatory attention on

reducing the societal burden of drug reactions and medication errors (Institute

of Medicine, 1999; U.S. Food and Drug Administra-tion, 1999; United States

General Accounting Office, 2000). As a result, greater attention and resources

are currently being devoted to signal generation and eval-uation by the FDA,

industry and academic centres. Moreover, efforts are underway to develop better

tools to manage recognized risks through a variety of inter-ventions, such as

communications with healthcare providers and patients, restricted product

distribution systems and other mechanisms. Additional effort is being focused

on measuring the success of these risk-management interventions. This new

initiative repre-sents a fundamental shift in the safety paradigm in the

successor in the United Kingdom to the Dunlop Committee, investigating this and

related problems, established a Working Party on Adverse Reactions. This group,

under the chairmanship of Professor David Grahame-Smith, published its second

report in July 1985. The report supported the continuation of methods of

spontaneous reporting by professionals but recommended that post-marketing

surveillance (PMS) studies should be undertaken on ‘newly-marketed drugs

intended for widespread long-term use’; the report also mentioned

record-linkage meth-ods and prescription-based methods of drug safety

surveillance as representing areas of possible progress (Mann, 1987).

Similar

reviews and conclusions have emerged from the United States since the

mid-1970s. A series of events in the United States recently created a

resurgence of interest in drug safety evaluation and management. The

Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) of 1992 provided additional resources at

the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for drug reviews through user fees and

established target time-lines for FDA reviews. The shorter approval times lead

to some medications being approved sooner in the United States than that in

Europe in contrast to the pre-PDUFA experience. A few highly visible drug

withdrawals led to a perception that perhaps drugs were being approved too

quickly. Lazarou, Pomeranz and Corey (1998) published the results of a

meta-analysis that estimated that 106 000 fatal adverse reac-tions occurred in

the United States in 1994. This and other articles (Wood, Stein and Woosley, 1998)

stimulated considerable public, congressional and regulatory attention on

reducing the societal burden of drug reactions and medication errors (Institute

of Medicine, 1999; U.S. Food and Drug Administra-tion, 1999; United States

General Accounting Office, 2000). As a result, greater attention and resources

are currently being devoted to signal generation and eval-uation by the FDA,

industry and academic centres. Moreover, efforts are underway to develop better

tools to manage recognized risks through a variety of inter-ventions, such as

communications with healthcare providers and patients, restricted product

distribution systems and other mechanisms. Additional effort is being focused

on measuring the success of these risk-management interventions. This new

initiative repre-sents a fundamental shift in the safety paradigm in the United

States and offers new challenges to phar-macovigilance professionals. In fact,

the shift is not restricted to the United States as both the FDA and the EMEA

in 2005 issued guidance documents for industry on signal detection, evaluation,

good pharma-covigilance practice and recommendations for manag-ing risks after

the approval (EMEA, 2005; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2005a–c).

We

have long recognized then that the safety of patients depends not only on drug

licensing by regu-latory bodies but also on post-marketing drug safety

surveillance, pharmacovigilance. It is also important to note that the same

post-marketing information needed to confirm new safety signals is also needed

to refute signals and protect the ability of patients to benefit from needed

medicines that may be under suspicion due to spurious signals.