The history of clinical pharmacy in the UK

| Home | | Hospital pharmacy |Chapter: Hospital pharmacy : Clinical pharmacy

Clinical pharmacy is now practised in all healthcare settings, but its main origins lie in the hospital sector. Until the mid-1960s, hospital pharmacists were mostly engaged in traditional pharmaceutical activities such as dispensing and manufacturing.

The history of clinical pharmacy in the UK

Clinical pharmacy is

now practised in all healthcare settings, but its main origins lie in the

hospital sector. Until the mid-1960s, hospital pharmacists were mostly engaged

in traditional pharmaceutical activities such as dispensing and manufacturing.

Then, the increasing range and sophistication of medicines available, awareness

of medication errors and the widespread use of ward-based prescription charts

brought pharmacists out of the dispensary and on to the wards in increasing

numbers.

This was initially

described as ‘ward pharmacy’ and was mostly a post hoc process with the

emphasis on the safe and timely supply of medicines in response to medical and

nursing demands. However, the service quickly evolved into something

significantly more proactive, seeing pharmacists inter-acting with patients and

other healthcare professionals and directly interven-ing in the patient care

process. The growth in these services over the 1970s and 1980s was said to

represent a change in hospital pharmacy from product orientation to patient

orientation and was formally acknowledged as ‘clinical pharmacy’ in the 1986

Nuffield report. The report welcomed these changes and recommended an increased

role for hospital pharmacists through the development of clinical pharmacy

services.

The recommendations

made in the Nuffield report were officially recog-nised in a 1988 Health

Services circular that outlined the main aims of the Department of Health with

respect to hospital pharmacy:

the achievement of better patient care and financial savings

through the more cost-effective use of medicines and improved use of

pharmaceutical services obtained by implementing a clinical pharmacy service.

A number of key

areas where pharmacist input could assist other clinicians and benefit patients

were highlighted, including contributing to prescribing decisions, monitoring

and modifying drug therapy, counselling patients and involvement in clinical

trials. The document acknowledged that, by helping to ensure patient safety and

appropriate use of medicines, clinical pharmacy services could prove to be

cost-effective.

As clinical pharmacy

services expanded, there was increasing specialisa-tion, with the expertise of

individual pharmacists in certain therapeutic areas contributing to more

significant developments in service provision. The speed of progress was

demonstrated in a review undertaken in the early 1990s, which showed that the

majority of NHS hospitals in the UK provided clinical pharmacy services and

most hospital pharmacists participated in ward-based clinical pharmacy activities.

However, the range of clinical pharmacy ser-vices varied enormously, from

almost 100% of hospitals having pharmacists who monitored drug therapy to less

than 10% for services such as infection control, clinical audit or medical

staff education. Since then, the widespread development of clinical pharmacy

services has continued, with significant expansion in the number and range of

services provided at most hospitals.

Wide variations in

the extent and nature of hospital clinical pharmacy services were also noted in

the Nuffield report and large differences still exist across much of the UK.

This lack of uniformity applies not just to clinical pharmacy, but also covers

almost every aspect of hospital pharmacy services. The absence of specific

directions from government and from the pharmacy profession, coupled with the

varying degrees of success with which individual pharmacy managers in each

hospital have been able to develop services, has allowed diversity to flourish

with wide variations in the proportion of time spent on clinical pharmacy

activities, ranging from less than 30% of pharma-cist time at some hospitals to

over 70% of pharmacist time at others. The Audit Commission recommended that

hospitals undertake reviews of their staffing levels and consider whether there

were adequate resources to provide all aspects of clinical pharmacy services,

so it is likely that the national figures on implementation of clinical

pharmacy services will be changing for some time.

One of the

differences between hospital and community pharmacy is the location of the

patient and how this affects the dynamics of providing clinical pharmacy

services. Most hospitals provide their pharmaceutical services to patients on

(but not exclusively) wards of various kinds. Thus, in order to deliver care

the pharmacist needs to visit the ward and interact with the patient, doctor,

nurse and others, as well as have access to consult and contribute to the

patient’s medical records.

Clinical pharmacist

presence on wards allows dialogue with patients and professionals in addition

to ensuring supplies of medicines are adequate for patients’ needs, and that

medicines are stored appropriately and safely. Pharmacy technicians, assistants

and others work with ward staff to provide effective supply of commonly used

items and, with the pharmacists, are increasingly leading the introduction of

the reuse of patients’ own drugs (PODs) schemes to reduce waste and, where

appropriate, patient self-medication to support concordance.

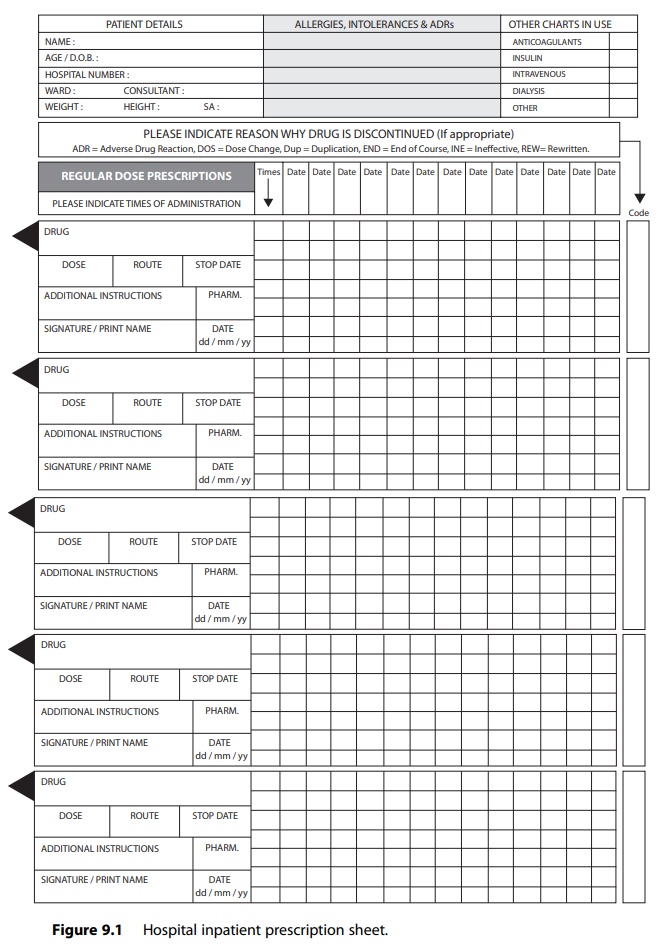

The importance of communicating

requests for medicines and the need to record administration of medicines have

led to the universal usage of the ward prescription chart. Various reports on

the value of recording the prescription and administration of medicines

emanated from situations where there was no record of them having been given.

Requiring nurses and doctors to record the administration of medicines offered

the rudiments of an audit trail for medicines.

The design and use

of these charts have consumed much time and energy from a variety of clinicians

in order to produce a hybrid document that serves the multiple purposes of

conveying: (1) patient details such as iden-tification, age, weight, gender and

allergies; (2) prescribing details such as medicine, form, dose, route and

frequency of administration and previous medicines; and (3) medicine

administration details including who adminis-tered (nurse, doctor, patient),

when and by which route. It also serves to indicate when a medicine has not

been given. An alert from the National Patient Safety Agency on reducing harm

from omitted and delayed medi-cines in hospital requires all healthcare

organisations to identify a list of critical medicines where timeliness of

administration is crucial.16 It also requires them to ensure that

medicine management procedures include guidance on the importance of

prescribing, supplying and administering critical medicines, timeliness issues

and what to do when a medicine has been omitted or delayed. Incident reports

should be regularly reviewed and an annual audit of omitted and delayed

critical medicines should be under-taken to ensure that system improvements to

reduce harms from omitted and delayed medicines are made. Figure 9.1 is an

extract from a typical hospital inpatient medicines chart.

The Welsh NHS took

this one step further in 2004 with the introduction of a new all-Wales

prescription chart, accompanied by prescription-writing standards and an

e-learning tool installed on the intranet systems of hospital trusts and

included in medical degree teaching.

The important sets

of prescription form data are essential for the efficient and effective

delivery of pharmaceutical care to the patient and also form the basis for the

development of electronic prescribing systems within the NHS. This is discussed

further in Chapter 15.

Related Topics