The Netherlands

| Home | | Pharmacovigilance |Chapter: Pharmacovigilance: Other Databases in Europe for the Analytic Evaluation of Drug Effects

The Dutch system of health care is based on GPs who practice in the community but not in the hospital, refer-ring ambulatory patients to specialists for outpatient or inpatient care.

THE NETHERLANDS

GENERAL PRACTICE SYSTEM

The

Dutch system of health care is based on GPs who practice in the community but

not in the hospital, refer-ring ambulatory patients to specialists for

outpatient or inpatient care. Specialists report their findings to the GP, who

acts as a gatekeeper. Approximately 90% of the patients’ presenting problems

are addressed by the GP (van der Lei et

al., 1993; Leufkens and Urquhart, 2005) time staff physicians who are

specialists of various kinds provide hospital care. Medical care, including

prescription drugs, is paid for by various insurers, which provide a basic

service to all citizens. Patients can only be registered with one GP but are

free to change, which happens infrequently and nearly always because the

patient moves out of the area. When a patient trans-fers, so does the record.

More than 75% of the patients will visit their GP at least once per year (van

derLei et al., 1993). The high degree

of computerization of GPs has given rise to the birth of several GP networks;

most of them are connected to one of the seven University Centres. One of the

largest research-oriented GP databases is the IPCI database, which has been

created with the specific purpose to conduct phar-macoepidemiological studies

(van der Lei et al., 1993; Vlug et al., 1999).

INTEGRATED PRIMARY CARE INFORMATION

In

1992, the IPCI Project was started by the Depart-ment of Medical Informatics of

the Erasmus Univer-sity Medical School, initially in collaboration with

Intercontinental Medical Statistics (IMS). In 1998, IMS stepped out, and since

then the database was run independently by the department of Medical

Informat-ics in collaboration with the Pharmacoepidemiology Unit. Integrated

Primary Care Information is a longi-tudinal observational database that

contains data from computer-based patient records of a selected group of GPs

throughout the Netherlands that voluntarily chose to supply data to the

database (Vlug et al., 1999). General

practitioners only receive a minimal reim-bursement for their data and control

usage of their data, through the Steering Committee and through the possibility

to withdraw data for specific studies. The collaborating GPs are comparable to

other Dutch GPs regarding age and gender.

As

of January 2005, there are 120 practices belong-ing to more than 150 GPs that

have provided data to the database. The first practice was recruited into the

IPCI project in 1994. Practices have therefore been supply-ing data for varying

periods. The database contains information on more than 700 000 patients. This

is the cumulative amount of patients who have ever been part of the dynamic

cohort of registered patients. Turnover occurs as patients move and transfer to

new practices. The records of ‘transferred out’ patients remain on the database

and are available for retrospective study with the appropriate time. As of

December 2005, there were 400 000 active patients registered with the

collaborat-ing GPs, 49% was male and 57% was insured through the Sickfund, and

the mean age was 38 years. In 2006, the IPCI database is expected to grow to

cover a popu-lation of 1 million active subjects. This is achieved by extending

data retrieval to GPs with other GP informa-tion systems than the original

ELIAS system alone. Data are downloaded on a monthly basis, and the information

is sent to the gatekeeper who anonimizes all information before further access

is provided.

The

database contains anonymous patient iden-tifiers, demographics and eligibility

dates (date of birth, sex, patient identification, insurance, date of

registration and transferring out and date of death), notes (subjective and

assessment text), symptoms, signs, prescriptions, and indications for therapy,

phys-ical findings, referrals, hospitalizations and labora-tory values. All

data are directly entered into a computer during the consultation hour where it

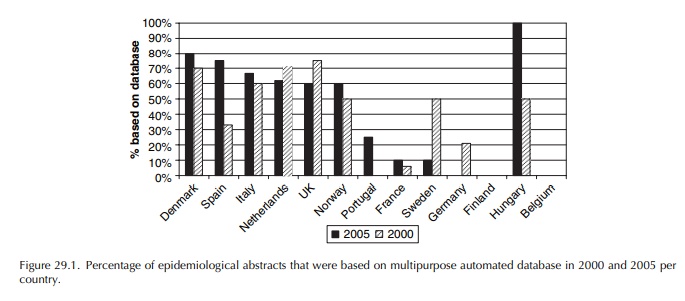

is stored (see Figure 29.1 for database structure). The International

Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) is the coding system for patient

complaints and diag-noses, but diagnoses and complaints can also be entered as

free text that is available as raw data (Lamberts and Wood, 1987). Prescription

data such as product name, quantity dispensed, dosage regi-mens, strength and

indication are entered into the computer to produce printed prescriptions (Vlug

et al., 1999). The National Database

of drugs, maintained by the Z-index, enables the coding of prescriptions,

according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification scheme

recommended by the WHO (de Smet, 1988).

Access to original medical records (discharge letters of hospitals) and administration of questionnaires to GPs is possible through the gatekeeper but only after approval of the IPCI Steering Committee. Data accu-mulated in the IPCI database have proven to be of high quality and suitable for epidemiological and pharma-coepidemiological research (Vlug et al., 1999). Data can be used for research purposes, but because of the privacy issues related to the presence of clinical notes access is possible only at the Erasmus Univer-sity Medical Centre and after approval of the Steering Committee.

The

database has been used for studies on disease occurrence (Eland et al., 2001, 2002; Verhamme et al., 2002; Straus et al., 2004a; van Soest et

al., 2005) and drug utilization

such as the change in prescriptions of terbinafine following a highly debated

press campaign (‘t Jong et al., 2004)

or appropri-ate prescribing in the elderly (van der Hooft et al., 2005); adherence and persistence with treatment ranging

from gastroprotection (Sturkenboom et al.,

2003a,b), antihypertensives, lipid lowering drugs, antidepressants and

respiratory drugs and the asso-ciation between adherence and treatment

outcomes; effectiveness of drugs and vaccinations (Voordouw et al., 2003, 2004; Dieleman et al., 2005); and last but not the least, a variety of adverse

drug reac-tions (Visser et al., 1996;

van der Linden et al., 1998, 1999; Straus

et al., 2004b, 2005). For a complete

updated list of publications, we refer to the website (www.ipci.nl).

Special

features of the database comprise the possi-bility to conduct randomized

database studies with naturalistic follow-up (Mosis, 2005a,b), pharmacoge-netic

studies and the possibility to return to patients and ask for additional

information, such as reasons for non-compliance, quality of life and blood

samples.

Related Topics