CIOMS III - Core Clinical Safety Information

| Home | | Pharmacovigilance |Chapter: Pharmacovigilance: CIOMS Working Groups and their Contribution to Pharmacovigilance

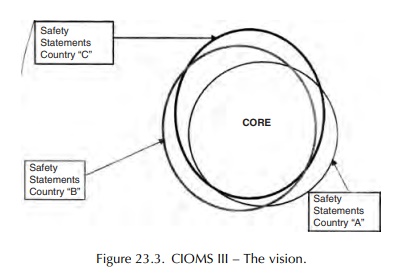

MS II introduced the concept of the core data sheet. It is a document prepared by the pharmaceutical manufacturer, containing the minimum essential safety information.

CIOMS III - CORE CLINICAL SAFETY

INFORMATION

RATIONALE

CIOMS

II introduced the concept of the core data sheet. It is a document prepared by

the pharmaceutical manufacturer, containing the minimum essential safety

information, such as ADRs, which the manufacturer stipulates should be listed

in all coun-tries where the drug is marketed (see Figure 23.3). It is also the

reference document by which ‘labelled’ and ‘unlabelled’ (or listedness and

unlistedness for ICH E2C) are determined. Thus, it should focus on the

important information required for rational clinical decision-making and

harmonise safety state-ments worldwide for public health and regulatory

purposes.

The

CIOMS III working group set out to propose principles and guidelines for

consistent decision-rules on the content of the Core Safety Information (CSI),

standard terms and definitions, and a standard format. One of the major

concerns was to minimise confusion among prescribers and other healthcare

professionals due to inconsistencies between the safety informa-tion presented

in different countries and by different manufacturers.

It

was therefore hoped that regulatory authori-ties would harmonise their basic

requirements for safety information in their local data sheets. However, the

working group acknowledged the possible need for cultural differences due to

medical and legal differences.

The

first edition of the CIOMS III report published in 1995 (CIOMS, 1995) focused

on CSI for marketed products, including the initial CSI that is prepared in

conjunction with the first market autho-risation submission, review and

approval. During CIOMS V discussions it was proposed that the same basic

philosophy and practices be applied to the safety information provided to

clinical investiga-tors during a development programme. The concept of

development core safety information (DCSI) as a discrete, focused section of

the Investigator’s Brochures, which would have the same format as, and would

evolve into, the CSI at initial marketing of the product, was therefore agreed.

A second edition of the CIOMS III report was issued in 1999 (CIOMS, 1999)

including the new proposals for Investigator’s Brochures.

PROCESS

The task of the working group was to develop propos-als for standard principles and guidelines addressing the what, when, how and where of CSI. The summary of product characteristics (SPC), the official document of the European Union, was used as a model to try to answer the following general questions:

• What evidence is needed, and how should it be used, to influence a decision on whether an adverse experience should be included, excluded or removed from the CSI?

• At what point in the accumulation and interpre-tation of information is the threshold crossed for inclusion or change in the CSI?

• What ‘good safety-labelling practices’ can be spec-ified concerning the clinical relevance of informa-tion, how it is expressed and the appropriateness of ‘class-labelling’?

• What should the sections of the CSI be called, how should they be defined and where should specific information be located?

At

the beginning of the process the group hoped to develop specific threshold

criteria, or an algorithm, for determining when information should be included

in the CSI. However, this was not possible and it became necessary to rely on

collective judgement to reach consensus. A series of case scenarios were

created from real-life examples for which the decision to amend a data sheet

was equivocal. Each member of the group was asked individually to make

decisions on the available data. In addition, each person was asked to list the

factors taken into consideration when reaching their conclusions. A total of 39

factors were identified and each member of the working group was asked to rank

the factors in order of importance. As expected, there was a considerable

divergence of opinion but overall the mostly highly ranked criterion for a

positive decision was the presence of positive rechallenge information. The

reader is referred to the original report for the remaining factors and their

respective rankings.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The

working group formulated a total of 65 propos-als relating to general

principles of good safety information and the what, when, how, where and who (responsibilities)

for CSIs. A selection of the most useful principles is given below.

What?

• The CSI should be determined by the needs of healthcare professionals in the context of a regula-tory and legal environment.

• Include what is practical and important to enable the prescriber to balance risks against benefit and to act accordingly.

• Avoid including events, especially minor events, that have no well-established relationship to therapy.

• There is a legal duty to warn but this must be balanced against the need to include only substan-tiated conclusions in the CSI.

• The CSI should include important information which physicians are not generally expected to know. (The converse is also true.)

When?

• As soon as relevant safety information becomes sufficiently well established it should be included in the CSI.

It

was not possible to define this more precisely but the working group introduced

the concept of ‘thresh-old’. This is dependent on the quality of information

available and the body and strength of the evidence according to the 39

criteria (plus two additional ones subsequently identified) in the ranking

exercise described above. Situations in which the threshold should be lowered

were identified. In general, infor-mation should be added sooner whenever it is

likely to help the physician make a differential diagnosis related to an

adverse event, spare extra tests, lead to the use of a specific targeted test

or facilitate early recognition of an event. Similarly, the thresh-old should

also be lowered if the ADR is medically serious or irreversible, if good

alternative drugs are available, a relatively trivial condition is being

treated, or the drug is being used for prophylaxis.

How?

• Keep ADRs identified in the initial CSI (pre-marketing experience) separate from those identi-fied subsequently.

• ADRs should be listed by frequency in body system order.

• Whenever possible, an estimate of frequency should be provided, expressed in a standard cate-gory of frequency.

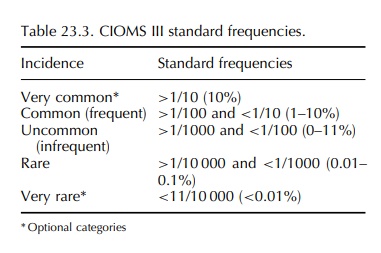

While

the working group recognised that precise frequency rates can only be obtained

from studies and are limited to the more common reactions, it was agreed that

estimates of frequency in a standard format should be provided whenever

possible. Although it is difficult to estimate incidence on the basis of spon-taneous

reports due to the uncertainties in estimating denominator and the degree of

under-reporting, the group recommended the standard frequencies shown in Table

23.3.

Finally,

the working group defined the safety sections of the CSI, providing guidance on

the infor-mation which should be included in each section and outlined the

responsibilities of the company for remaining diligent and proactive, including

undertak-ing the scientific investigation of signals. The shared responsibility

of healthcare providers, patients, editors of medical journals and regulators

is also addressed.

INCORPORATION IN REGULATION

Since

the standards proposed by the CIOMS III working group would require continuous

evaluation, updating and refinement, it was suggested that they be retained as

guidelines and not adopted as regu-lations. They have been used as the basis of

the European Labelling Guidelines and many regulatory authorities have adopted

the standard categories of frequency. However, during the most recent

redraft-ing of the European Labelling Guidelines there was discussion regarding

their appropriateness when spon-taneous reports are the only source of data for

esti-mating frequency.

Related Topics