Medically Important Fungal Pathogens of Humans

| Home | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology |Chapter: Pharmaceutical Microbiology : Fungi

The yeast C. albicans is an opportunistic fungal pathogen which can be present as a normal part of the body’s microflora. C. albicans is also responsible for a range of systemic infections and many of these can start as superficial infections.

MEDICALLY IMPORTANT FUNGAL PATHOGENS OF HUMANS

Candida albicans

The yeast C. albicans is an opportunistic fungal

pathogen which can be present as a normal part of the body’s microflora. C. albicans is also responsible for a

range of systemic infections and many of these can start as superficial

infections. Infection of the gastrointestinal tract is seen in diabetics,

cancer patients and people with AIDS; the oesophagus is a common site of

infection, rendering swallowing difficult. The urinary tract can also be the

site of candidosis which may be due to renal infection, other underlying disease(s)

or cystitis. The presence of an indwelling urinary catheter may also predispose

to Candida infection.

A range of factors are

capable of predisposing the individual to superficial or systemic candidal

infections. Factors which impair the host’s immune system such as the presence

of underlying disease (AIDS, cancer, diabetes), the use of immunosuppressive

therapy during organ transplantation and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy can

leave the individual susceptible to candidosis. Other factors that may

predispose to Candida infection

include the presence of indwelling catheters and skin damage as a result of

burns or other trauma.

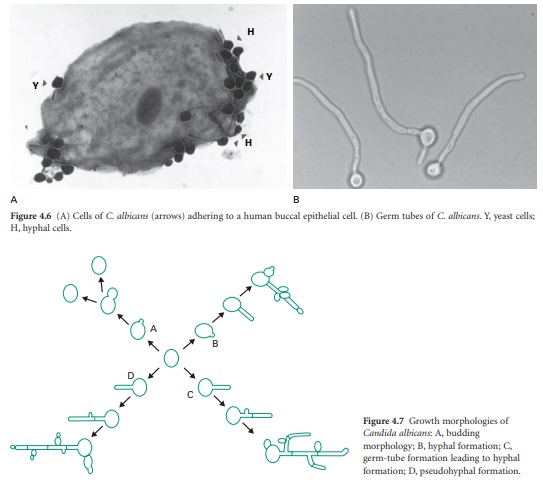

C. albicans displays a variety of virulence factors which aid colonization and persistence in the body. One of the most important

of these factors is the ability to adhere to host tissue using a variety of

mechanisms (Figure 4.6A). The importance of adherence may be illustrated by the

ability of C. albicans to adhere to

various mucosal surfaces and to withstand forces that may lead to its removal

from the body, such as the bathing/washing action of body fluids. A hierarchy

exists among Candida species

indicating that the more common etiological agents of candidosis (C. albicans and Candida tropicalis) are more adherent to host tissue in vitro than relatively non-pathogenic

species such as C. krusei and Candida guilliermondii.

C. albicans can exist in two morphologically distinct forms: budding blastospores or hyphae (Figure 4.6B).

The yeast can switch

between each form and is usually encountered in tissue samples in both

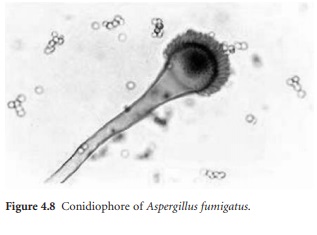

morphological forms (Figure 4.7). The hyphae are capable of thigmo-tropism

(contact sensing) which may aid in finding the line of least resistance between

and through layers of cells in tissue. C.

albicans produces a range of extracellular enzymes which facilitate

adherence and/or tissue penetration. Phospholipases A, B, C and lyso-phospholipase

may function to damage host cell membranes and facilitate invasion. C. albicans produces a range of acid

proteinases which have been shown to aid adherence and invasion but which also

play an important role in the degradation of the immunoglobulins IgG and IgA.

There are now known to be 10 members of the secreted aspartic proteinase (SAP)

family and these have a low pH optimum which may assist in the colonization of

the vagina. Haemolysin production by C.

albicans has also been documented and seems to be important in allowing the

yeast access iron released from ruptured red blood cells. An important immune

evasion tactic of C. albicans is the

ability to bind to platelets via fibrinogen binding ligands which results in

the fungal cell being surrounded by a cluster of platelets.

C. albicans is capable of giving rise to a variety of interconvertible phenotypes which can be considered as providing

an extra dimension to the existing virulence factors associated with this

yeast. A number of switching systems have been identified and phenotypic

switching may have evolved to compensate for the lack of variation achieved in

other organisms that utilize sexual reproduction. Phenotypic switching allows

the yeast to exploit microniches in the body and alters a variety of factors

(e.g. antifungal drug resistance, adherence, extracellular enzyme production)

in addition to the actual phenotype and so may be considered as the ‘dominant’

or ‘controlling’ virulence factor.

In terms of tissue

colonization and invasion, adherence is the initial step in the process. Once

the yeast has adhered, enzymes (phospholipase and proteinase) can facilitate

adherence by damaging or degrading cell membranes and extracellular proteins.

Hyphae may be produced and penetrate layers of cells using thigmotropism to

find the line of least resistance. The passage through cells is undoubtedly

aided by the production of extracellular enzymes. Once endothelial cells are

reached enzymes may assist in the degradation of tissue and allow the yeast

enter the host’s blood stream where phenotypic switching or coating with platelets

may be used to evade the immune system. While in the bloodstream the haemolysin

may function to burst blood cells and release iron which is essential for

growth. Escape from the bloodstream involves adherence to the walls of

capillaries and passage across the wall.

Aspergillus fumigatus

Aspergillus fumigatus is a saprophytic fungus which is widely distributed in nature where it

is frequently encountered growing on decaying vegetation and damp surfaces

(Figure 4.8 ). A. fumigatus can

present as an opportunistic pathogen of humans and is the commonest etiological

agent of pulmonary aspergillosis, being responsible for 80–90% of cases.

Although the incidence of disease due to Aspergillus

species is less than that due to Candida,

aspergillosis results in greater mortality rates.

A. fumigatus produces a number of extracellular enzymes which facilitate growth in the lung and dissemination

through the body. Phospholipase production has been shown in clinical isolates

of this fungus with optimal production occurring at 37 °C. This enzyme plays a

critical role in tissue degradation and may facilitate exit of the fungus from

the lung into the bloodstream. Fungal proteases are responsible for tissue

degradation and neutralization of the immune system and probably evolved to

allow the fungus to degrade animal and plant material. Elastin constitutes

almost 30% of lung tissue and many A.

fumigatus isolates display elastinolytic activity while isolates incapable

of elastinase production display reduced virulence in mice. A. fumigatus produces two elastinases: a

serine protease and a metalloproteinase. Apart from their direct role in tissue

degradation, A. fumigatus proteases

(in particular the serine protease) may also function as allergens which may be

important in the induction and persistence of allergic aspergillosis. Local

inflammation due to the presence of proteases results in airway damage and in vitro studies have shown that

proteases are capable of inducing epithelial cell detachment from basement

membranes. Such desquamation may partly explain the extent of damage seen in

the lungs of asthmatic and cystic fibrosis patients affected with allergic

aspergillosis. In addition proteases induce the release of the proinflammatory

IL6 and IL8 cytokines in cell lines derived from airway epithelial cells, which

may induce mucosal inflammatory response and subsequent damage to the surrounding

tissue.

The production and

secretion of toxins into surrounding tissues by the proliferating fungus is

regarded as an important virulence attribute and may facilitate fungal growth

in the lung. Gliotoxin is the main toxin produced by A. fumigatus , others include helvolic acid, fumigatin and

fumagillin. It is believed that toxins play a significant role in facilitating

the colonization of the lung by A.

fumigatus since they can act to retard elements of the local immunity.

Significantly, Aspergillus species

that do not produce toxins to the same extent

as A. fumigatus isolates are rarely seen

in clinical cases.

Histoplasma capsulatum

Histoplasma capsulatum is a dimorphic fungus which is the cause of histoplasmosis, the most prevalent fungal pulmonary

infection in the USA. Histoplasmosis is common amongst AIDS patients but is

also found among infants and elderly people living in endemic areas who may be

susceptible to infection due to impaired immune function. The mortality rate

among infants exposed to a large dose of H.

capsulatum may be 40–50%. H.

capsulatum grows in the mycelial form in soil while in tissue it is encountered as round, budding cells. Its natural

habitat is soil that has been enriched with the droppings of bats or birds, and

disturbance of such soil by natural (e.g. wind) or human (e.g. agriculture)

activities releases large numbers of airborne spores that upon inhalation can

establish pulmonary infection in individuals or in populations distant from the

original source of spores.

Upon inhalation of H. capsulatum pulmonary macrophages

engulf the yeast cells and provide a protected environment for the yeast to

multiply and disseminate from the lungs to other tissues. The ability to

survive within the hostile environment provided by the macrophage is the key to

the success of H. capsulatum as a pathogen.

Normal individuals who inhale a large number of H. capsulatum spores can develop a nonspecific flulike illness

associated with fever, chills, headache and chest pains after a 3 week

incubation period that resolves without treatment. Chronic pulmonary

histoplasmosis is seen in men in the 45–55 year age group who may have been

exposed to low levels of spores over a long period of time. The condition is

progressive, leading to a loss of lung function and death if untreated.

Cryptococcus neoformans

Crypotococcus neoformans is an encapsulated yeast that is most frequently associated with

infection in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with AIDS, where

meningitis is the most common clinical manifestation. C. neoformans is a facultative intracellular pathogen that is

capable of surviving and replicating within macrophages and withstanding the

lytic activity within these cells. In order to survive within macrophages C. neoformans appears to accumulate

polysaccharides within cytoplasmic vesicle. As part of its survival strategy C. neoformans

also produces melanin, which has the ability to bind and protect against microbicidal peptides. In addition,

melaninization may allow the cell withstand the effects of harmful hydroxyl

radicals and so survive in hostile environments . The capsule of C. neoformans is a virulence factor in

that it protects the cell from the immune response, and capsular material

(glucuronoxylomannans) induces the shedding of host cell adherence molecules

required for the migration of host inflammatory cells to the site of infection,

thus explaining the reduced inflammatory response to this yeast.

In immunocompromised

patients pulmonary infection can lead to disseminated forms of the disease

where the eyes, skin and bones become infected. Cryptococcal meningitis is

particularly associated with AIDS patients where it is a major cause of death.

While cryptococcosis may be controlled by antifungal therapy, in AIDS patients

there is a danger of relapse unless antifungal therapy is constantly

maintained.

Dermatophytes

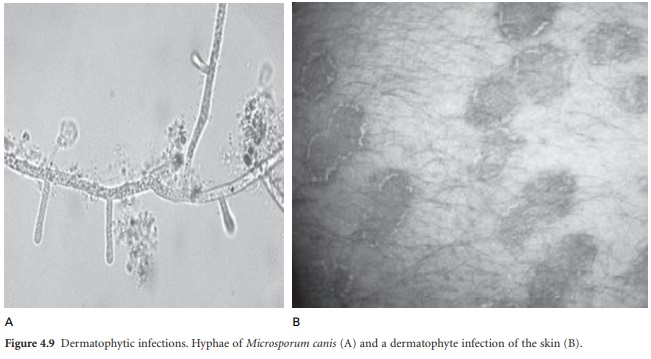

The dermatophytes are a

group of keratinophilic fungi which can metabolize keratin— the principal

protein in skin, nails and hair (Figure 4.9). Tinea capitis is defined as the

infection of the hair and scalp with a dermatophyte, usually Microsporum canis or Trichophyton violaceum. In Europe and

North Africa T. violaceum may be responsible for approximately 60% of

cases of tinea capitis. This condition is characterized by a mild scaling and

loss of hair and in some cases it may be contagious. Tinea corporis is

characterized by infection of the skin of the trunk, leg and arms with a

dermatophyte and is usually caused by Trichophyton

spp., Microsporum sp. or Epidermophyton floccosum. Lesions are

itchy, dry and show scaling.

Typically lesions retain a circular morphology and the condition is often

referred to as ‘ringworm’. Tinea cruris is seen where the skin of the groin is

infected with a dermatophytic fungus, usually Epidermophyton floccosum or Trichophyton rubrum. This condition is highly contagious via fomites (towels,

sheets, etc.) and up to 25% of patients show recurrence following antifungal

therapy. Tinea pedis presents as infection of the feet with a dermatophyte; it

is very common and easily contracted. The principal fungi responsible for this

condition are T. rubrum and E. floccosum and

the sites of infection may include

the webs of the toes, the sides of the feet or the soles of the feet. Tinea

manuum is a fungal infection of the hands and can be caused by a range of fungi

most notably Trichophyton mentagrophytes.

Infection is often seen in association with eczema and can result from

transmission of fungi from another infected body site. Tinea unguium is defined

as infection of the fingernails or toenails and is often described as onychomycosis,

which includes infections due to a range of other fungi, bacteria and nail

damage associated with certain disease states (e.g. psoriasis).

Related Topics