General Structure of Viruses

| Home | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology |Chapter: Pharmaceutical Microbiology : Viruses

Viruses are extremely diverse in size and in structure. The smallest virus is approximately 28 nm in size (poliovirus), while the largest is 750 nm (mimivirus). In simplistic terms, a virus consists of viral nucleic acid within a protein core, the capsid (also referred to as the coat)

GENERAL STRUCTURE OF VIRUSES

Viruses are extremely

diverse in size and in structure. The smallest virus is approximately 28 nm in

size (poliovirus), while the largest is 750 nm (mimivirus). In simplistic

terms, a virus consists of viral nucleic acid within a protein core, the capsid (also referred to as the coat),

possibly surrounded by a lipidic envelope

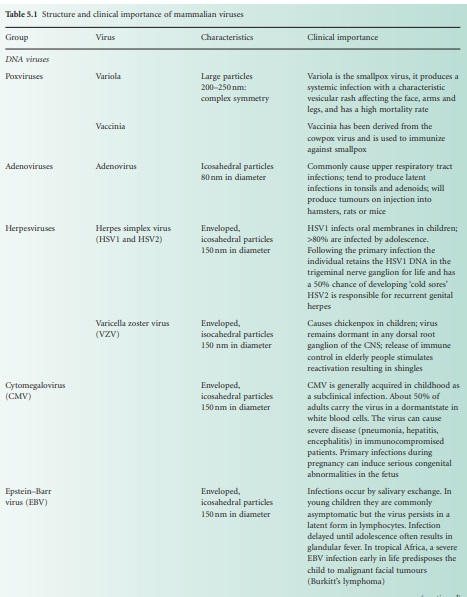

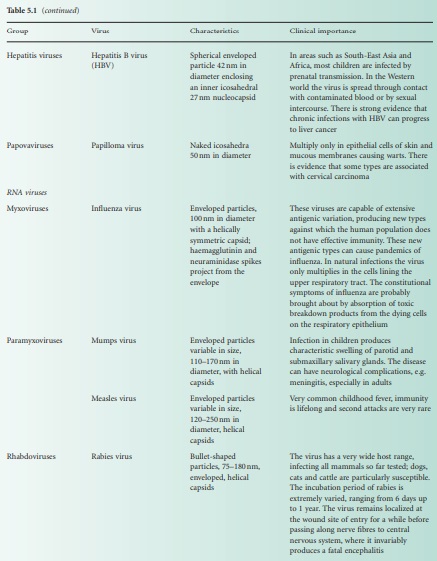

(Table 5.1). In reality, there are many differences between viruses in terms of

nucleic acid, capsid structure, number of coats and envelope composition. Such

differences account for the high diversity of viruses and the differences in

their properties, notably their resistance to antiviral drugs and viricidal agents.

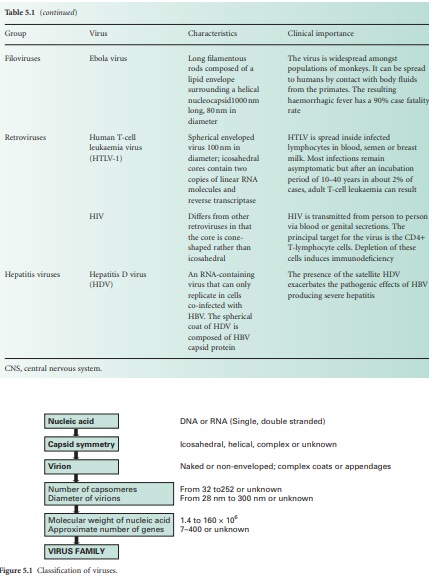

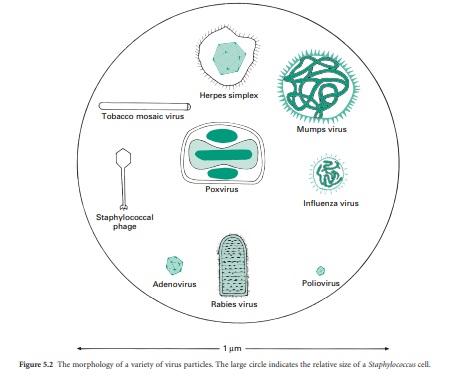

Viral classification (Figure 5.1) is based on the physical and chemical

properties of viruses, their structure and morphology (Figure 5.2).

Viral nucleic acid

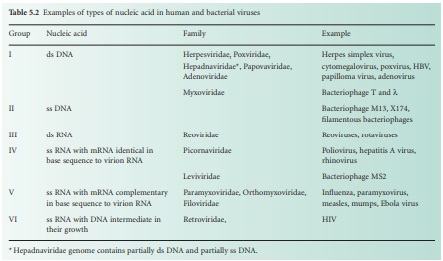

The viral genome is

composed of either DNA or RNA. It can be double stranded (ds) or single-stranded

(ss), linear (e.g. poliovirus) or circular (e.g. hepatitis B virus), containing

several segments (e.g. influenza—eight segments of minus sense ss RNA) or one

molecule (e.g. poliovirus). Six groups can be distinguished depending on their

nucleic acid content (Table 5.2). Viruses that contain plus sense ss RNA (e.g.

poliovirus) can have their genome translated directly by the host ribosome. The

nature of the viral nucleic acid is important for the effectiveness of

antiviral treatments (see below). For example, retroviridae such as HIV require

a specific virus-encoded enzyme, a reverse transcriptase, to convert their ss

RNA into ss DNA, to be able to replicate within the host cell. This enzyme is a

primary target site of many antiviral drugs.

On some occasions, the

viral genome has been shown to be infectious, i.e. to cause an infection. Such

an observation is important when one considers viricidal agents that damage the

viral capsid or envelope but not the viral nucleic acid. Furthermore, in laboratory

conditions, the phenomenon of multiplicity

reactivation has been observed with poliovirus whereby random damage to

viral capsid and nucleic acid following treatment with hypochlorite, a biocide

intensively used for surface disinfection, resulted in complementary

reconstruction of an infectious particle by hybridization of the gene pool of

the inactivated virus. This again underlines the necessity of rendering the

viral nucleic acid non-infectious following a viricidal treatment.

Viral capsid

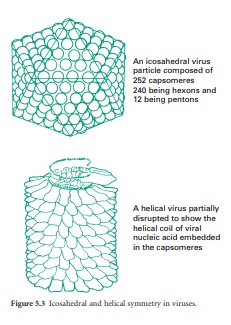

The function of the capsid is to protect the viral nucleic acid from detrimental chemical and physical conditions (e.g. disinfection). The capsid is composed of a number of subunits named capsomeres genetically encoded by the viral genome. The nature and association of the capsomeres are fundamental for the virus, as they give the shape of the capsid, but also provide the virus with resistance to chemical and physical agents. The assembly of the capsomeres results in two different architectural styles— icosahedral and helical symmetries (Figure 5.3); in mammalian viruses, a more complex structure can be found, where several proteinaceous structures envelope the viral genome core (e.g. poxviruses, rhabdoviruses). Bacterial viruses (bacteriophages) also show a complex structure consisting of a capsid head, a tail and tail fibres. The nature of the capsomeres in certain viruses allows for the self-assembly of the capsid within the host cell. The capsomeres are held together by noncovalent intermolecular forces. Such assembly also allows the release of the viral genome following dissociation of the noncovalently bonded subunits. These subunits offer considerable economy of genetic information within the viral genome since only a small number of different subunits contribute to the formation of the capsid. Viruses with an icosahedral capsid usually have capsomeres in the form of pentons and hexons. The number of these subunits varies considerably between viruses: for example, adenovirus is constructed from 240 hexons and 12 pentons, whereas the poliovirus is composed of 20 hexons and 12 pentons, forming a much smaller structure. Viruses with a helical capsid (e.g. influenza and mumps viruses) have their subunits symmetrically packed in a helical array, appearing like coils of wound rope under electron microscopy. Although the core of such a virus is hollow, the viral nucleic acid is embedded into ridges on the inside of each subunit and does not fill the hollow core. Such a close association between viral nucleic acid and capsid proteins can explain the damage caused to the nucleic acid following disaggregation of the capsid after chemical or physical treatments.

Viral envelope

The viral capsid can be

surrounded by a lipidic envelope, which originates from the host cell. The

envelope is added during the replication process or following excision of the

viral progeny from the host cells. The envelope can come from the host cell

nuclear membrane (e.g. herpes simplex virus) or the cytoplasmic membrane (e.g.

influenza virus). One characteristic of the viral envelope is that host

proteins are excluded, but proteins encoded by the viral genome are present.

These viral proteins play an important serological role. Enveloped viruses are

generally considered to be the most susceptible to chemical and physical

conditions and do not survive well on their own outside the host cell (e.g. on

surfaces), although they can persist longer in organic soil (e.g. blood,

exudates, faeces). Lipids in viruses are generally phospholipids from the host

envelope, although glycolipids, neutral fats, fatty acids, fatty aldehydes and

cholesterol can be found.

Viral receptors

In addition to these

structures, glycoproteins can be found usually protruding from the viral capsid

or embedded in the envelope. These virus-encoded structures are important for

viral infectivity as they recognize the host cell receptor site conveying viral

specificity. In bacteriophages, these structures can take the shape of tail

fibres.

Related Topics