Static Beds of Nonporous Solids

| Home | | Pharmaceutical Technology |Chapter: Pharmaceutical Engineering: Drying

Drying of wet granular beds, the particles of which are not porous and are insoluble in the wetting liquid, has been extensively studied.

STATIC BEDS OF NONPOROUS SOLIDS

Drying

of wet granular beds, the particles of which are not porous and are insoluble

in the wetting liquid, has been extensively studied. The operation is presented

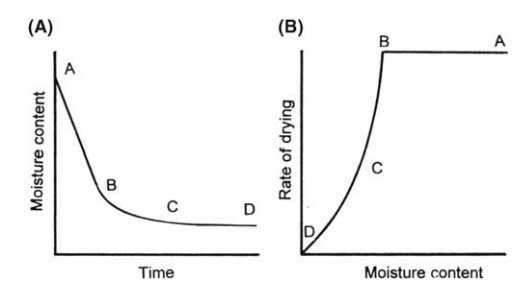

as the relation of moisture content and time of drying in Figure 7.3A. It

should be noted that the equilibrium moisture content is approached slowly. A

protracted period may be required for the removal of water just above the equilibrium

value. This is not justified if a small amount of water can be tol-erated in

further processing and indicates the importance of establishing

FIGURE 7.3 (A) Moisture content versus

time of drying and (B) rate of drying versus moisture content.

The stability of the solids, maintained, as shown later, at a

temperature close to that of the drying air, may allow unnecessary

deterioration.

The data has been

converted to a curve relating the rate of drying to moisture content in Figure

7.3B. The initial heating-up period during which equilibrium is established is

short and has been omitted from both figures.

Assuming that

sufficient moisture is initially present, the drying rate curve exhibits three

distinct sections limited by the points A, B, C, and D.

In section AB,

called the constant rate period, it

is considered that moisture is evaporating from a saturated surface at a rate

governed by diffusion from the surface through the stationary air film in

contact with it. An analogy with evaporation from a plain water surface can

therefore be drawn. The rate of drying during this period depends on the air

temperature, humidity, and speed, which in turn determine the temperature of

the saturated surface. Assuming that these are constant, all variables in the

drying equations given above are fixed and a constant rate of drying is

established, which is largely independent of the material being dried. The

drying rate is somewhat lower than that for a free water surface and depends to

some extent on the particle size of the solids. During the constant rate

period, liquid must be transported to the surface at a rate sufficient to

maintain saturation. The mechanism of transport is discussed later.

At the end of the

constant rate period, B, a break in the drying curve occurs. This point is

called the critical moisture content, and a linear fall in the drying rate

occurs with further drying. This section, BC, is called the first falling rate

period. At and below the critical moisture content, the movement of moisture

from the interior is no longer sufficient to saturate the surface. As drying

pro-ceeds, moisture reaches the surface at a decreasing rate and the mechanism

that controls its transfer will influence the rate of drying. Since the surface

is no longer saturated, it will tend to rise above the wet bulb temperature.

For

any material, the critical moisture content decreases as the particle size

decreases. Eventually, moisture does not reach the surface that becomes dry.

The plane of evaporation recedes into the solid, the vapor reaching the surface

by diffusion through the pores of the bed. This section is called the second

falling rate period and is controlled by vapor diffusion, a factor which will be

largely

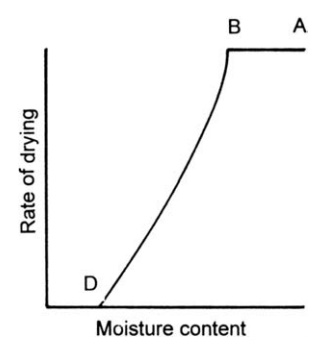

FIGURE 7.4 Drying curve for a skin-forming

material.

independent

of the conditions outside the bed but markedly affected by the particle size

because of the latter’s influence on the dimensions of pores and channels.

During this period, the surface temperature approaches the temper-ature of the

drying air.

Considerable

migration of liquid occurs during the constant rate and first falling rate

periods. Associated with the liquid will be any soluble constituents that will

form a concentrating solution in the surface layers as drying proceeds.

Deposition of these materials will take place when the surface dries.

Consider-able segregation of soluble elements in the cake can, therefore, occur

during drying.

If

the soluble matter forms a skin or gel on drying rather than a crystalline

deposit, a different drying curve, shown in Figure 7.4, is obtained. The

constant rate period is followed by a continuous fall in the drying rate in

which no differentiation of first and second falling rate periods can be made

(hence “C” is not identified in Fig. 7.4). During this period, drying is

controlled by diffusion through the skin that is continually increasing in

thickness. Soap and gelatin are solutes that behave in this way.

Related Topics