Status of Oral Hypoglycaemics in Diabetes Mellitus

| Home | | Pharmacology |Chapter: Essential pharmacology : Insulin, Oral Hypoglycaemic Drugs and Glucagon

After 8 years of prospective study involving large number of patients, the University Group Diabetes Programme (UGDP) of USA (1970) presented findings that cardiovascular mortality was higher in patients treated with oral hypoglycaemics than in those treated with diet and exercise alone or with insulin.

STATUS OF ORAL HYPOGLYCAEMICS IN DIABETES MELLITUS

After 8 years of

prospective study involving large number of patients, the University Group

Diabetes Programme (UGDP) of USA (1970) presented findings that cardiovascular

mortality was higher in patients treated with oral hypoglycaemics than in those

treated with diet and exercise alone or with insulin. A decline in their use followed.

Subsequent studies both refuted and supported these conclusions.

The controversy has

now been settled; UK PDS found that both sulfonylureas and metformin did not

increase cardiovascular mortality over > 10 years observation period.

Related to degree of glycaemia control, both insulin and sulfonylureas reduced

microvascular complications in type 2 DM, but did not have significant effect

on macrovascular complications. Metformin, however, could reduce macrovascular

complications as well; it decreased risk of death and other diabetes related

endpoints in overweight patients. This may be related to the fact that both

sulfonylureas and exogenous insulin improve glycaemic control by increasing

insulin supply rather than by reducing insulin resistance, while metformin can

lower insulin resistance. The thiazolidinediones are another class of drugs

which reverse insulin resistance, and have been found to reduce macrovascular

complications and mortality in type 2 DM. All oral hypoglycaemics do however

control symptoms that are due to hyperglycaemia and glycosuria, and are much

more convenient than insulin.

Oral hypoglycaemics

are indicated only in type 2 diabetes, when not controlled by diet and

exercise. They are best used in patients with—

i.

Age above 40 years at onset of disease.

ii.

Obesity at the time of presentation.

iii.

Duration of disease < 5 years when starting

treatment.

iv.

Fasting blood sugar < 200 mg/dl.

v.

Insulin requirement < 40 U/day.

vi.

No ketoacidosis or a history of it, or any

other complication.

Introduced in the

prediabetic ‘impaired glucose tolerance phase’, sulfonylurea + dietary regulation

has been shown to postpone manifest type 2 DM. This may be due to the fact that

hyperglycaemia is a self perpetuating condition. The Diabetes Prevention Programme

(2002) has established that in middle aged, obese prediabetics metformin

prevented progression to type 2 DM, but not in older nonobese prediabetics.

Glitazones appear to have similar potential. Longterm acarbose therapy can also

prevent type 2 DM.

Oral hypoglycaemics

should be used to supplement dietary management and not to replace it.

Metformin is preferred in obese type 2 patients: its anorectic action aids

weight reduction and it has the potential to lower risk of myocardial

infarction and stroke. The g.i. tolerance of metformin is poorer and its

patient acceptability is less than that of sulfonylureas. Moreover, the

sulfonylureas appear to produce greater blood sugar lowering. As such, many

patients are treated initially with a sulfonylurea alone. Metformin can be used

to supplement sulfonylureas in patients not adequately controlled by the

latter.

There is no difference

in the clinical efficacy of different sulfonylureas. This however does not

signify that choice of drug is irrelevant. Differences between them are mainly

in dose, onset and duration of action which governs flexibility of regimens. The

second generation drugs are dose to dose more potent, produce fewer side

effects and drug interactions, and are commonly used, but no spectacular features

have emerged.

Chlorpropamide is not recommended

because of long duration of action,

greater risk of hypoglycaemia, jaundice, alcohol flush, dilutional hyponatraemia

and other adverse effects. Tolbutamide

is less popular due to low potency, but may be employed in the elderly to avoid

hypoglycaemia. Glibenclamide and glyclazide are suitable for most patients, but have been found to cause

hypoglycaemia more frequently. Glipizide

is preferred when a faster and shorter acting drug is required. Glimepiride is a newer sulfonylurea,

claimed to have stronger

extrapancreatic action by enhancing GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane,

thus causing lesser hyperinsulinaemia.

A low incidence of

hypoglycaemic episodes has been reported with glimepiride. This may be due to

its ability to preserve hypoglycaemia induced glucagon release and suppression

of insulin release, responses that are attenuated by glibenclamide. Glimepiride

is suitable for once daily dosing due to gradual release from tissue binding.

Even in properly selected

patients, sulfonylureas may fail from the beginning (primary failure 5–28%) or

become ineffective after a few months or years of satisfactory control (secondary

failure 5–10% per year): may be due to progressive loss of β cells, reduced

physical activity, continuing insulin resistance, drug and dietary

noncompliance or desensitization of receptors. If one sulfonylurea proves

ineffective in a patient, another one (especially a second generation) may still

work. Combined use of a sulfonylurea and a biguanide may be tried if either is

not effective alone and the glitazones are now available as add on/alternative

drugs. Patients with marked/only posprandial hyperglycaemia may be treated with

repaglinide/ nateglinide. Upto 50% patients of type 2 DM initially treated with

oral hypoglycaemics ultimately need insulin. Despite their limitations, oral

hypoglycaemics are suitable therapy for majority of type 2 DM patients.

However, when a diabetic on oral hypoglycaemics presents with infection, severe

trauma or stress, pregnancy, ketoacidosis or any other complication or has to

be operated upon—switch over to insulin (see

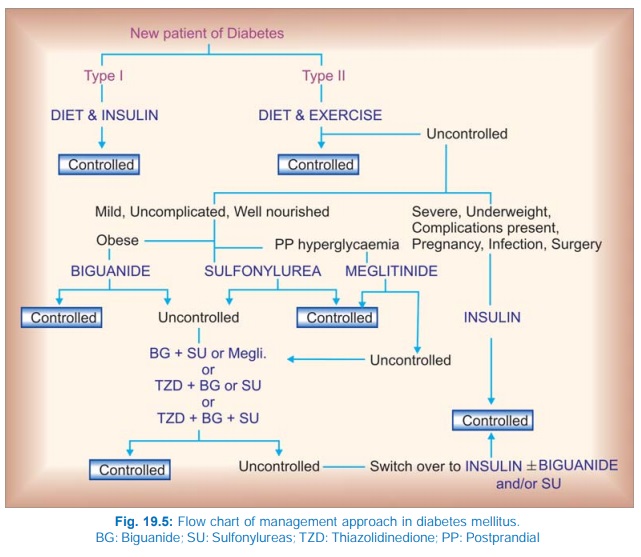

Fig. 19.5).

Sulfonylureas and

metformin can also be combined with insulin, particularly when a single daily

injection of longacting insulin is used to provide basal control, the oral

hypoglycaemics given before meals serve to check postprandial glycaemia.

Guargum

It

is a dietary fibre (polysaccharide) from Indian cluster beans

(Guar), which forms a viscous gel on contact with water. Administered just

before or mixed with food, it slows gastric emptying, intestinal transit and

carbohydrate absorption: postprandial glycaemia is suppressed but overall

lowering of blood glucose is marginal. It also reduces serum cholesterol by

about 10%.

Guargum can be used to supplement diet and to lower sulfonylurea

dose, and as a hypocholesterolemic. It is not absorbed but fermented in the

colon. Side effects are flatulence, feeling of fullness, loss of appetite,

nausea, gastric discomfort and diarrhoea. Start with a low dose (2.5 g/day) and

gradually increase to 5 g TDS.

DIATAID, CARBOTARD 5 g

sachet.

Glucomannan

This

powdered extract from tubers of Konjar is promoted as

a dietary adjunct for diabetes. It swells in the stomach by absorbing water and

is claimed to reduce appetite, blood sugar, serum lipids and relieve

constipation.

DIETMANN 0.5 g cap, 1

g sachet; 1 g to be taken before meals.