Strategic medicines management in practice

| Home | | Hospital pharmacy |Chapter: Hospital pharmacy : Strategic medicines management

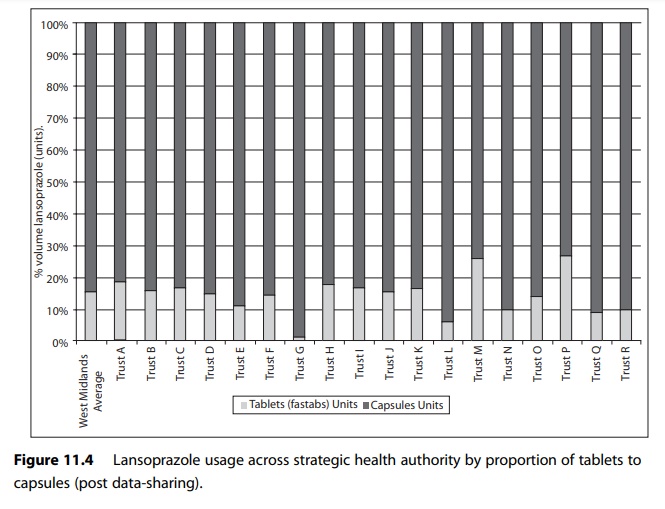

In describing various approaches to implementing strategic medicines management in practice, it is appropriate to discuss the issue in the context of the medicines management pyramid.

Strategic medicines management in practice

In describing

various approaches to implementing strategic medicines management in practice,

it is appropriate to discuss the issue in the context of the medicines management

pyramid shown in Figure 11.1. As can be seen from the diagram, there are three

key elements to strategic medicines management:

·

managed entry of new medicines

·

prescribing policies and guidelines

·

monitoring and feedback on medicines use.

Managed entry of new medicines

At a national level

the entry of new medicines is controlled in the licensing process by the

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA); only medicines with

an appropriate product licence may be mar-keted in the UK. However, the MHRA

licence is primarily concerned with whether a new medicinal product works and

is no less safe than existing medicines. The MHRA licensing process makes no

judgement on the cost-effectiveness of a new medicine. The establishment of the

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in England in 1999

was an attempt to introduce a system to assess the cost-effectiveness of new

and established medicines. NICE is discussed further in the section on

prescribing policies and guidelines, below.

The cornerstone of

any system to manage the introduction of new medi-cines at health economy or

trust level is the medicines formulary.

Formularies

In the 2007 review

of acute trusts medicines management systems, 88% of trusts reported they had a

formulary – a published list of preferred med-icines to be used within the

organisation. A view many hospitals take is that prescribing information is

contained in the British National Formulary, and the purpose of a local

formulary is to inform the prescrib-ing doctor what medicines are available for

prescription within the organ-isation or health economy. Historically,

formularies have been applied to junior doctors, whereas consultants have been

allowed to prescribe out-side this restricted list. However, with increased

management control, rising drug expenditure and the advent of clinical

governance, some hos-pital formularies have been applied rigorously to all

grades of staff, including consultants. Clearly, when implementing such a

policy it is necessary to make arrangements for the exceptional clinical

situation, since a limited range of medicines may not be sufficient to cover

every clinical situation.

Deciding the content

of the formulary is usually the responsibility of the hospital drug and therapeutics

or medicines management committee. It is important that such decisions are

evidence-based and transparent if the for-mulary is to improve prescribing and

be owned by prescribers. When consid-ering the evidence for new medicines, a

number of questions need to be addressed:

·

What is the safety profile of the medicine?

·

Is it better or worse than existing medicines?

Clearly, an

application would fail if the new medicine had significantly more side-effects

than the current standard treatment unless there were exception-ally large

benefits. Therefore, newer ‘black triangle’ medicines may require a more

cautious approach.

In addition:

·

What is the efficacy of the new medicine?

·

Are there any advantages over what is already available?

Often benefits are marginal and need to be balanced against cost.

Finally:

·

What are the financial implications of the new medicine to

the organisation or health economy?

Hospitals must

consider the cost to primary care if treatment is to be con-tinued. In

particular ‘loss-leading’ should be avoided, where a pharmaceutical company

sets the price in hospital artificially low in order to get a drug used,

whereas the drug is very expensive in primary care.

One way of ensuring

both primary and secondary care issues are consid-ered when making formulary

decisions is to have a joint hospital–primary care formulary covering a whole

health economy.

In order to inform

formulary decisions, the published evidence about the new medicine should be

reviewed by someone with critical appraisal skills. This is often a medicines

information pharmacist or, in larger hospitals, a dedicated formulary

pharmacist.

Formularies are an

effective way of controlling the introduction of new medicines in hospital,

because the hospital pharmacy controls the medicines supply chain. However, in

primary care, formularies can only be advisory, since the suppliers (the

community pharmacy) are independent contractors. PCTs use a variety of methods

to encourage compliance with formularies. These can include PCT medicines

management teams amending practice computer systems, and prescribing targets in

the GP quality outcomes frame-work scheme.

The Healthcare

Commission recommended that formularies be linked to evidence-based guidelines.

Medicines management committees

Drug and therapeutic (D&T) committees have been established in most hospitals in the UK for many years. Their role in facilitating the develop-ment of formularies was endorsed in the Department of Health circular, HC (88)54, issued in the late 1980s.In a survey of hospitals in 1994, 97% indicated they had a D&T committee. More recently, in the Healthcare Commission’s review of acute hospitals medicines management, all trusts reported they had such a committee. D&T committees or, as a number are now called, medicines management committees are a multidisciplinary group reporting to the chief executive, medical director or management board and their remit is to look at prescribing issues in the trust. Table 11.1 shows the range of activities reported by D&T committees.

Table 11.1 Activities at drug and therapeutic (D&T) committees

Activity : % D&Ts undertaking

Evaluating medicines : over 90%

Developing medicines policy : circa 90%

Reviewing treatment guidelines : 85–90%

Considering financial effectiveness of medicines : 80–85%

Overseeing errors and incidents : 75–80%

Medicines risk management analysis : circa : 75%

Medication alerts : circa 70%

Medicines spend versus budget : 65–70%

Training for medicines for staff groups : 50–55%

Implementation and training on new medicines : 50–55%

D&T committees

have played an important role in controlling the introduction of new medicines

and managing medicines policies in hospitals for over 30 years. However, with

the establishment of PCTs in 2002, and more recently their changing role as

commissioners of services, it has become clear that there needs to be a

joined-up approach to effective medicines management across health economies.

This can be effectively achieved through area prescribing committees, either

undertaking the role of individual organisations committees or as an umbrella

committee into which the various organisations committees feed, and which takes

the final decision on health economy formulary. The latter is more likely,

since within a health economy there may be a mixture of acute, mental health

and social care trusts. Furthermore, the establishment of clinical networks,

particularly cancer networks, which have their own therapeutics commit-tees,

adds to the potential plethora of decision-making committees around medicines,

and requires overall coordination, particularly in relation to formulary

decisions.

Funding new medicines

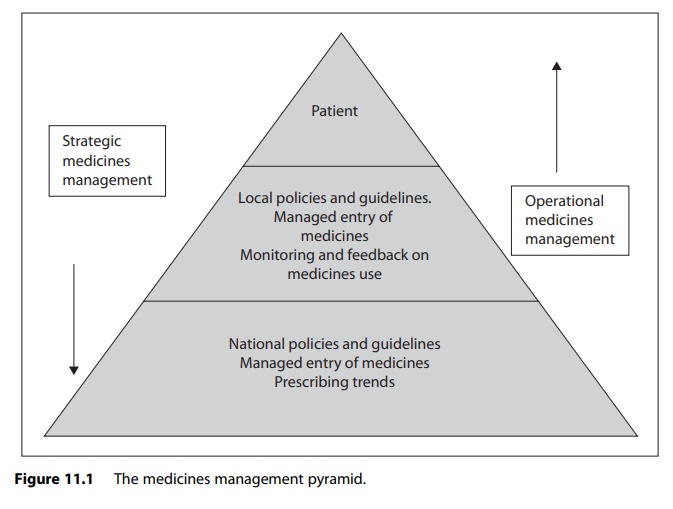

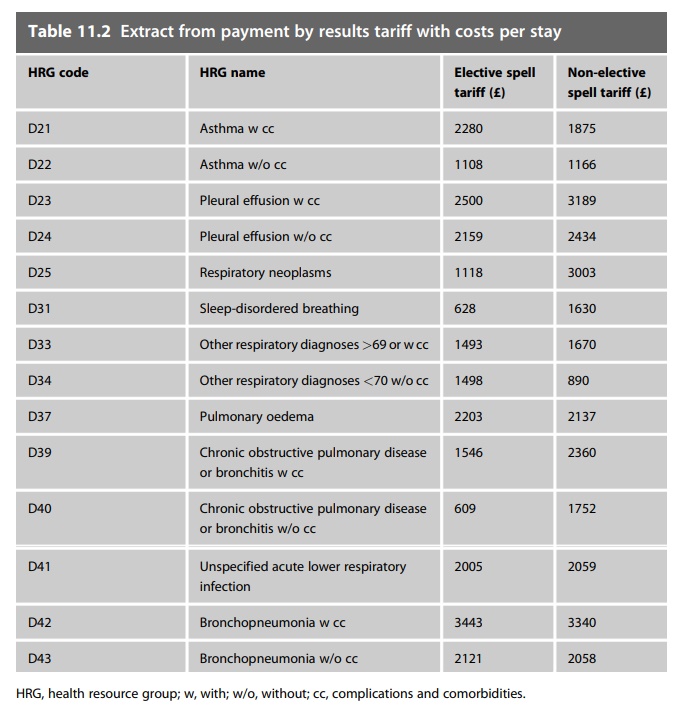

A further

complication in managing the introduction of new medicines into a hospital, and

ultimately a health economy, is the development of PCTs as commissioners of

health services and the NHS tariff system (Chapter 1 dis-cusses the payment by

results system). The tariff has various prices within it for particular

treatments depending on whether there are complications and varying lengths of

stay. Table 11.2 is an example of the 2008–2009 tariff payments for

respiratory-related treatments. Usually the tariff payment includes the cost of

medicines used; the hospital is expected to fund the medicines treatment from

the tariff payments it receives.

Medicines budgets in

most hospitals have been devolved to clinical direct-orates so applications for

the introduction of new medicines from consultants usually require financial

sign-off by the directorate management team supporting the application. The

process is further complicated by medi-cines excluded from tariff. Medicines

excluded from tariff are expensive medicines whose cost is not covered by the

tariff income. In these cases PCTs pay for these excluded medicines separately.

The mechanism varies between different health economies, but often involves

recharging the cost to the patient’s PCT. Therefore, an application for funding

to the PCT, usually through the hospital contracting and commissioning system,

has to be made for formulary applications involving these medicines. For

hospi-tals that are tertiary referral centres, such as cancer centres, the

patient’s PCT may not be the local host PCT, adding a further complication to

the process. Figure 11.2 illustrates the medicines management process in the

author’s health economy showing how complex the process can be if all

stakeholders are to be involved.

Prescribing policies and guidelines

National guidance

At a national level

the most authoritative guidance is that issued by NICE. Prior to 1999,

hospitals had discretion as to which new medicines were prescribed there. If

funding a new medicine was problematic, decisions were taken in conjunction

with the district health authority. This resulted in vari-ations in

availability of new medicines across the whole NHS – so-called postcode

prescribing. NICE was established in 1999 with the explicit remit of

eliminating postcode prescribing.

The terms of

reference for NICE were:

·

to reduce inequalities in treatment

·

to produce evidence-based guidance on treatments

·

to identify new developments which will most improve patient

care

·

to help protect patients from outdated and inefficient

treatments. With respect to medicines, there are two key types of NICE

guidance: clinical guidelines and technology appraisals.

Clinical guidelines

are recommendations by NICE on the appropriate treat-ment and care of people

with specific disease conditions. The guidelines are based on the best

available evidence but it is recognised that these are guide-lines and cannot

replace the health professional’s knowledge and skill being applied to specific

patients.

Technology

appraisals are recommendations on the use of new and exist-ing medicines and

treatments within the NHS; for medicines they usually focus on one or a small

group of medicines. The recommendations are based on NICE’s review of clinical

and economic evidence. Unlike clinical guidelines there is a statutory

obligation (in England) for medicines supported by a technology appraisal to be

funded via the NHS.

Whilst NICE

guidelines and technology appraisals are based on critical review of clinical

and economic evidence, they also take into account the views of stakeholders,

including patient groups and the pharmaceutical industry.

NICE outputs are

aimed at the NHS in England and Wales, though they are accessed much more

widely. In Scotland, the Scottish Medicines Consortium provides guidance on

medicines that may be used. Its remit is to provide advice to NHS boards and

their D&T committees about the status of all newly licensed medicines, all

new formulations of existing medicines and new indications for established

products. The All Wales Strategy Group undertakes a similar role.

There are other

types of national guidelines produced by Royal Colleges and organisations such

as the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. The NHS Health Information

Resources (formerly the National Library for Health) provides a single portal

for accessing these guidelines through its website (www.library.nhs.uk).

Searching by disease on the guidance section of the website, various guidelines

can be accessed through hyperlinks to the appropriate guideline producer.

At a more local

level, guidelines can take a variety of forms such as complete care pathways

designed around a particular disease state and include instructions on the use

of medicines. The advantage is that the pre-scribing message is an integral

part of the care pathway the doctor will be using rather than a separate

guideline.

A good example of

this is the West Mercia guidelines that have been developed by a consortium of

hospitals in the West Midlands and North West of England. The guidelines are

then individualised by each hospital (for example, to complement local

formularies). These guidelines take the practitioner through the whole

treatment of a particular event, including diagnostic tests and medicines to be

used. Other guidelines focus mainly on the use of medicines.

The most widely used

example of local guidelines focusing on the medi-cines is antibiotic

guidelines. The emergence of resistance to antibiotics first gained national

attention in the UK with the publication of the House of Lords inquiry. This

was followed by the Standing Medical Advisory Committee report and the

Department of Health document Getting Ahead of the Curve. The latter resulted

in the Department of Health allocating £12 million to establish antibiotic

pharmacists within hospitals in England, as discussed in Chapter 9. The need

for such posts has been further strengthened by the association of certain

antibiotics with Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea (CDAD). Antibiotic

guidelines are a tool that is central to this area of work, which can take a

variety of forms, but need to be readily accessible, and in a form that can be

easily understood. Leeds teaching hospi-tals have developed a web-based set of

antimicrobial guidelines that can be searched by body system.

Monitoring and feedback on medicines use

Clearly, if senior

management is to be aware of prescribing issues, there needs to be a robust

system for collating and reporting information on medicines usage. All hospital

pharmacies have computerised stock control systems for medicines. These systems

have been designed around purchasing and stock control, and not producing

prescribing reports. However, the main suppliers of these systems have built in

reporting modules in newer versions, although the ease of reporting varies from

system to system. Prescribing reports can be used for a variety of purposes.

The most common is providing feedback to clinical directorates on medicines use

and expenditure for budget manage-ment purposes. Most hospitals are managed on

a directorate structure, whereby wards or clinical specialties are grouped

together as a clinical directorate, with their own budget and management team. The

directorate usually has a clinician as clinical director who is supported by a

manager, financial accountant and human resources manager. In large hospitals,

these clinical directorates may be grouped into clinical divisions (that is,

medicine, surgery, and so on) that are directly accountable to and represented

on trust management boards. A survey published in 1997 indicated that 77% of

drug budgets were devolved to clinical directorates. The Audit Commission in

its review of acute hospitals medicines management systems showed that 21% of

trusts managed the drug budget at directorate level, 27% at specialty level and

45% at ward/consultant level, with only 6% managing the budget at trust level.

In the same review 96% of budget-holders received medicines budget reports. In

many hospitals these reports are supported by directorate pharmacists, a

concept which was established over a decade ago. These pharmacists are employed

by the pharmacy to provide prescribing advice at clinical directorate level.

In the author’s own

trust directorate pharmacists present prescribing reports to their clinical

directorates, usually at directorate governance meet-ings. These reports

address not only financial issues but also clinical issues and prescribing

initiatives either specific for the directorate or across the trust. More

recently we have introduced a system where common prescribing errors picked up

by clinical pharmacists on the wards are fed back to clinical teams as a

learning exercise. This non-blame approach has resulted in a reduction in

prescribing errors.

Since much of the

work at directorate level involves reviewing medicines usage data and producing

graphical representation of prescribing trends, pharmacy technicians are now

being employed to support directorate pharmacists.

Medicines management

reports are also produced for trust level commit-tees. In view of the increased

interest in antibiotic use, particularly as a relationship has been established

that antibiotics predispose patients to develop CDAD, antibiotic-prescribing

reports are presented regularly to the trust’s infection prevention group.

Although monitoring

of medicines use has a long history in hospitals, there is no national

comparison of hospital prescribing similar to the system which exists in

primary care using practice detailed prescribing information data, previously

called PACT data. This is detailed information on an individual primary care

practice prescribing patterns, and allows PCTs to compare practice prescribing

patterns to PCT and national patterns.

A project was

initiated over a decade ago by the National Prescribing Centre (NPC) to

undertake comparison of hospital prescribing patterns. This aimed to collect

detailed prescribing information routinely from a cohort of hospitals. The

results of this pilot project showed some interesting trends, but it proved

impossible to roll out across the whole of the NHS because there are a variety

of commercial pharmacy systems being used with no common identifier for

medicines. Computerised prescribing linked with electronic patient records will

alleviate this problem and provide better information on hospital prescribing

patterns, since usage data can be linked to individual patients and diagnosis.

More importantly, where computerised prescribing has been implemented, it has

delivered significant improvements in the quality of patient care. However, the

national information technology project to develop electronic prescribing for

hospitals that was aimed to be in place by 2004 has now largely been abandoned,

and individual trusts are developing their own solutions. This suggests that

the problems identified in the NPC project over a decade ago will still remain.

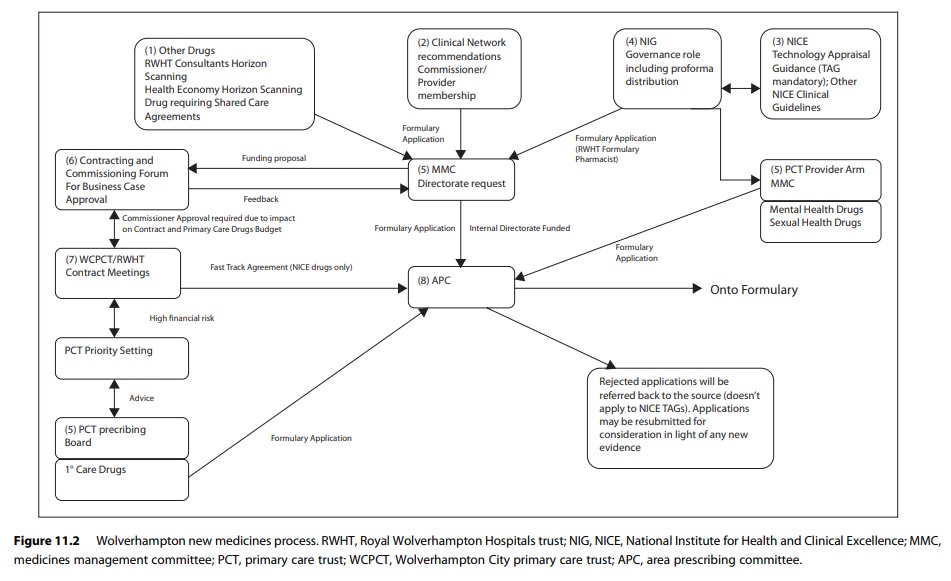

More recently the

concept of comparing medicines use across hospitals has been resurrected.

However, the methodology is much different from that adopted by the NPC. In

this new initiative the author and colleagues have used existing data sets,

such as IMS and PharmEx data, which are already collected routinely from

hospital pharmacy computer systems. However, even when data are available,

comparing hospitals of different size, activity and case mix is problematic. We

are developing tools to compensate for these variables, such as defined daily

dose/finished consultant episode and propor-tionality. We have shown that it is

possible to support change in hospital medicines use using such comparative

data.

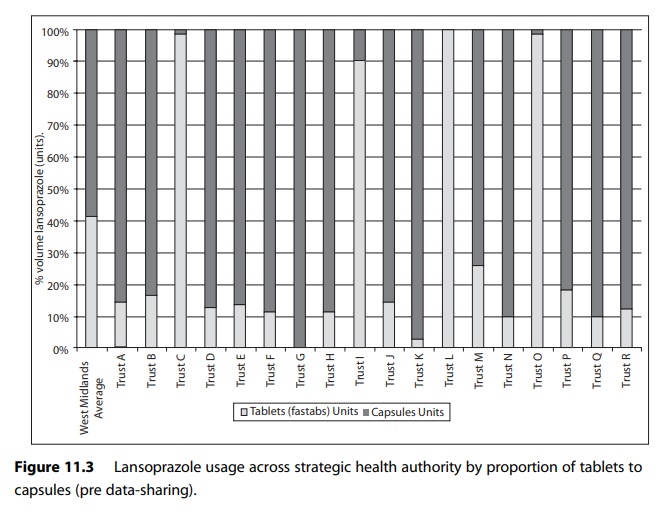

For example, Figure

11.3 shows use of different formulations of lansoprazole expressed in terms of

proportionality to compensate for activity variable in a group of hospitals in

one English strategic health authority.

Figure 11.4 shows the use in the same cohort of hospitals after an action plan to reduce the use of tablet formulation of lansoprazole was put in place.