Treatment of Epilepsies

| Home | | Pharmacology |Chapter: Essential pharmacology : Antiepileptic Drugs

Antiepileptic drugs suppress seizures, but do not cure the disorder; the disease may fadeout though after years of successful control. The aim of drugs is to control and totally prevent all seizure activity at an acceptable level of side effects.

TREATMENT OF EPILEPSIES

Antiepileptic drugs suppress seizures, but do not cure the

disorder; the disease may fadeout though after years of successful control. The

aim of drugs is to control and totally prevent all seizure activity at an

acceptable level of side effects. With the currently available drugs, this can

be achieved in about half of the patients. Another 20–30% attain partial

control, while the rest remain resistant. The cause of epilepsy should be

searched in the patient; if found and treatable, an attempt to remove it should

be made. Some general principles of symptomatic treatment with antiepileptic drugs

are:

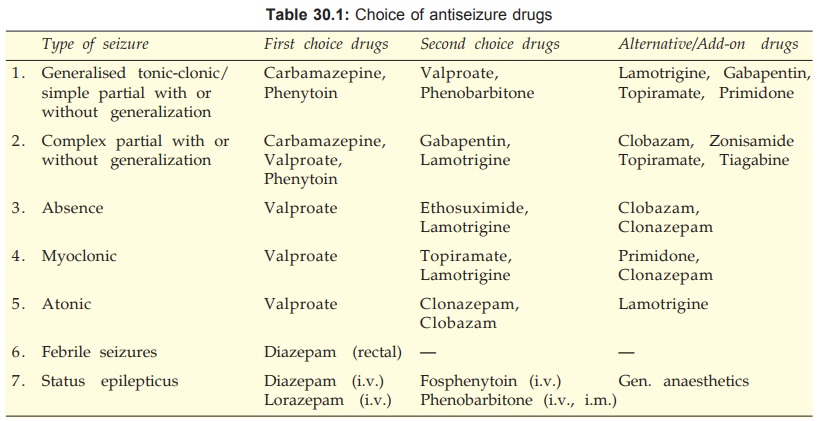

1.

Choice of drug (Table 30.1) and dose is

according to the seizure type(s) and need of the individual patient.

2. Initiate treatment early, because each seizure

episode increases the propensity to further attacks, probably by a process akin

to kindling. Start with a single drug, preferably at low dose— gradually

increase dose till full control of seizures or side effects appear. If full

control is not obtained at maximum tolerated dose of one drug, substitute

another drug. Use combinations when all reasonable monotherapy fails. Combining

drugs with different mechanisms of action, such as those which prolong Na+

channel inactivation with those facilitating GABA appears more appropriate.

Pharmacokinetic interactions among anticonvulsants are common; dose adjustments

guided by therapeutic drug monitoring are warranted.

3. Therapy should be as simple as possible. A seizure diary

should be maintained.

4. All drug withdrawals should be gradual (except

in case of toxicity), abrupt stoppage of therapy without introducing another

effective drug can precipitate status epilepticus. Prolonged therapy (may be

lifelong, or at least 3 years after the last seizure) is needed. Withdrawal may

be attempted in selected cases. Factors favourable to withdrawal are—childhood

epilepsy, absence of family history, primary generalized tonic-clonic epilepsy,

recent onset at start of treatment, absence of cerebral disorder and normal EEG.

Even then recurrence rates of 12–40% have been reported.

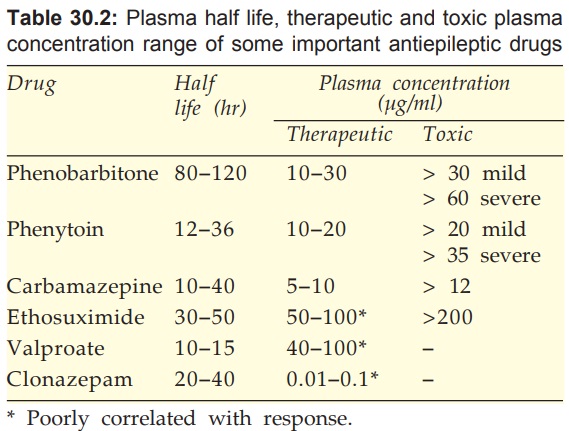

5. Dose regulation may be facilitated by monitoring of steady state

plasma drug levels. Monitoring is useful because:

•

Therapeutic range of concentrations has been

defined for many drugs.

•

There is marked individual variation in the plasma

concentration attained with the same daily dose.

•

Compliance among epileptic patients is often

poor.

Plasma levels given in Table 30.2 are to serve as rough guides:

6. When women on antiepileptic therapy conceive, antiepileptic

drugs should not be stopped. Though, most antiseizure drugs have been shown to

increase the incidence of birth defects, discontinuation of therapy carries a high

risk of status epilepticus. Fits occurring during pregnancy themselves increase

birth defects and may cause mental retardation in the offspring (anoxia occurs

during seizures). An attempt to reduce the dose of drugs should be cautiously

made. It may be advisable to substitute valproate.

Prophylactic folic acid supplementation in 2nd and 3rd trimester

along with vit. K in the last month of pregnancy is recommended, particularly

in women receiving antiepileptic drugs to minimise neural tube defects and bleeding

disorder respectively in the neonate.

7. Individual seizure episodes do not require

any treatment. During an attack of tonic-clonic seizures, the first priority is

to prevent injury due to fall or biting. The patient should be put in prone or

lateral position and a gag should be placed between the teeth. The head should

be turned and patency of airway ensured. The attack usually passes off in 2–3

min, but the patient may not be roadworthy for a couple of hours.

A. Generalised Tonic-Clonic And Simple Partial Seizures

In large comparative

trials, considering both

efficacy and toxicity, carbamazepine and phenytoin have scored highest,

phenobarbitone was intermediate, while primidone was lowest. Carbamazepine was

the best in partial seizures, while valproate was equally effective in

secondarily GTCS. Valproate is a good second line drug but should be used

cautiously in young children for fear of hepatic toxicity. Carbamazepine is

preferred in young girls because of cosmetic side effects of phenytoin.

Lamotrigine, gabapentin and topiramate have emerged as good

alternatives. Newer drugs are to be used as addon therapy in cases with

incomplete/poor response or even as monotherapy in selected patients to avoid

drug interactions and side effects. The newer drugs are less sedating and

produce fewer side effects.

Complete control can be obtained in upto 90% patients with

generalized seizures, but in only 50% or less patients with partial seizures.

Phenobarbitone, phenytoin, valproate and carbamazepine have been

used to treat early post head injury seizures. Phenobarbitone and phenytoin are

often prescribed empirically for prophylaxis of lateonset (8 days to 2 yrs

later) posttraumatic epilepsy, but risk/benefit ratio of such use is not clear.

Decision has to be taken on individual basis.

B. Complex Partial Seizures

This type of epilepsy is difficult to control completely;

relapses are more common on withdrawal. Carbamazepine is the preferred drug,

but phenytoin or valproate may have to be added to it. Phenobarbitone or primidone

could be used with one of the above drugs. The newer drugs clobazam,

lamotrigine, gabapentin and topiramate may be added in refractory cases.

C. Absence Seizures

Ethosuximide and valproate

are equally efficacious, but the latter is more commonly used because it would

also prevent kindling and emergence of GTCS. Valproate is clearly superior in

mixed absence and GTCS, which is more common than pure absence seizures.

Lamotrigine has emerged as a good alternative. Clonazepam is a second line drug

limited by its sedative property and development of tolerance. Clobazam is an

alternative with promise of more sustained response.

D. Myoclonic And Atonic Seizures

Valproate

is the preferred drug and lamotrigine is an effective alternative. Topiramate

may be added in case of poor response. Primidone and clonazepam are occasionally

used.

E. Febrile Convulsions

Some children, especially

under 5 years age, develop convulsions during fever. These may recur every time

with fever and few may become chronic epileptics. Every attempt should be made

to see that they do not develop fever,

but when they do, the temperature should not be allowed to rise by using

paracetamol and external cooling.

The best treatment of febrile convulsions is rectal diazepam 0.5

mg/kg given at the onset of convulsions. The i.v. preparation can be used; a

rectal solution (5 mg in 2.5 ml) in tubes is available in the UK. Seizures

generally stop in 5 min; if not another dose may be given. The drug is repeated

12 hourly for 4 doses. If fever is prolonged a gap of 24–48 hr is given before

starting next series of doses.

In recurrent cases or those at particular risk of developing

epilepsy—intermittent prophylaxis with diazepam (oral or rectal) started at the

onset of fever is recommended. Chronic prophylaxis with phenobarbitone

advocated earlier has been abandoned, because of poor efficacy and behavioral

side effects.

F. Infantile Spasms (Hypsarrhythmia)

Therapy is unsatisfactory,

antiepileptic drugs are generally useless. Corticosteroids afford symptomatic

relief. Valproate and clonazepam have adjuvant value. Vigabatrin has some

efficacy.

G. Status Epilepticus

In status epilepticus seizure activity occurs for >30 min, or two

or more seizures occur without recovery of consciousness. Recurrent tonic-clonic

convulsions without recovery of consciousness in between is an emergency; fits

have to be controlled as quickly as possible to prevent death and permanent

brain damage.

•

Diazepam 10 mg i.v. bolus injection (2 mg/

min) followed by fractional doses every 10 min or slow infusion titrated to

control the fits has been the standard treatment. However, it redistributes

rapidly so that anticonvulsant effect starts fading after 20 min. Lorazepam is

less lipid soluble with slow redistribution: anticonvulsant effect of i.v. dose

lasts for 6–12 hours. It is therefore preferred; 0.1 mg/kg (injected at 2 mg/

min) is effective in 75–90% cases.

•

Phenobarbitone (100–200 mg i.m./i.v.) or

phenytoin (25–50 mg/min in a running saline i.v. line; not to be mixed with

glucose solution because it precipitates. Fosphenytoin is used in its place

now; maximum 1000 mg phenytoin equivalent). These drugs act more slowly; may be

used alternatively to diazepam/lorazepam or substituted for them after the

convulsions have been controlled.

•

Refractory cases may be treated with i.v.

midazolam/propofol/thiopentone anaesthesia, with or without curarization.

• General measures, including maintenance of

airway (intubation if required), oxygenation, fluid and electrolyte balance,

BP, normal cardiac rhythm, euglycaemia and care of the unconscious must be taken.