Types of Joint Movements

| Home | | Anatomy and Physiology | | Anatomy and Physiology Health Education (APHE) |Chapter: Anatomy and Physiology for Health Professionals: Support and Movement: Articulations

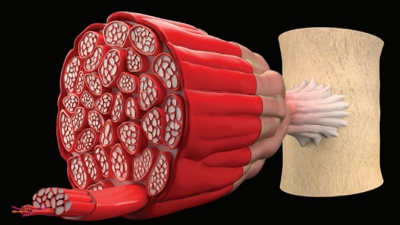

Movements at synovial joints are produced by skeletal muscle action.

Types of

Joint Movements

Movements at synovial joints are

produced by skeletal muscle action. In most joints, one end of a muscle is

attached to a primarily immovable or fixed part and the other end is attached

to a movable part. During mus-cle contraction, the movable end (insertion) is

pulled toward the fixed end (origin), with movement occur-ring at the joint.

Movements are described in directional terms. These relate to the axes (lines)

around which a body part moves, and the body planes through which movement

occurs. Nonaxial movement involves only slipping movements, because there is no axis around which

the movement can take place. Uniaxial movement is movement within one plane, whereas biaxial movement is movement in two planes.

Multiaxial

movement is movement in or

around all three planes of space and axes. Range of motion varies widely

between individuals. There are general forms of movement, which include

angular, gliding, and rota-tional movements. There are general forms of

move-ment, which include angular, gliding, and rotation.

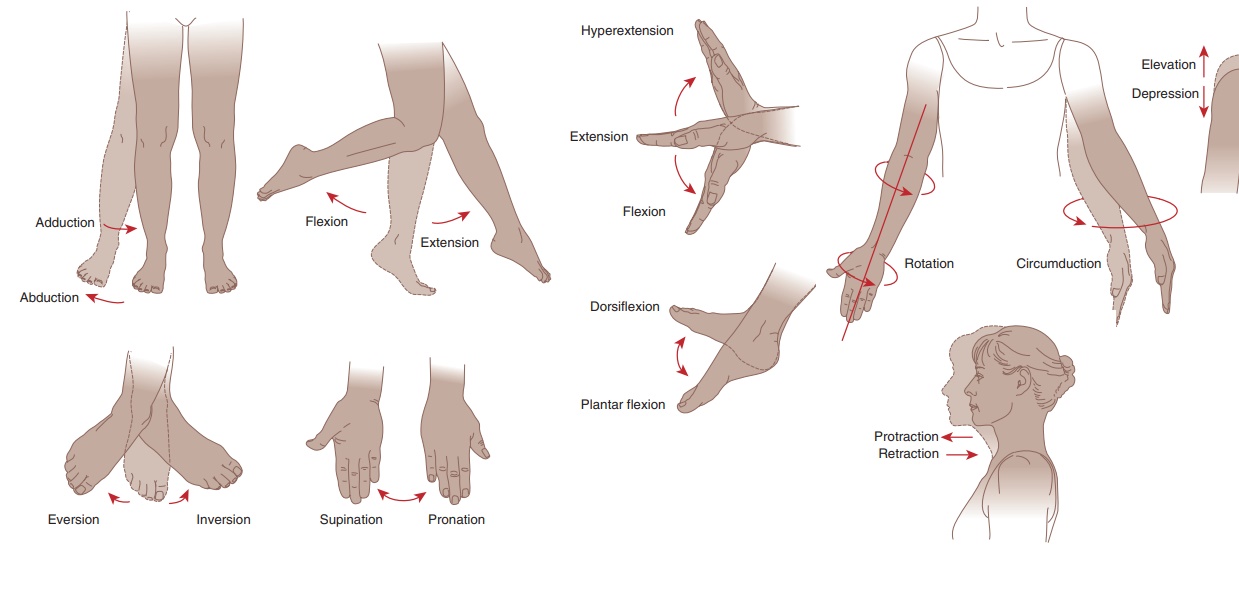

Angular Movements

Angular

movements decrease or increase

the angle between two bones. This can occur in any body plane and

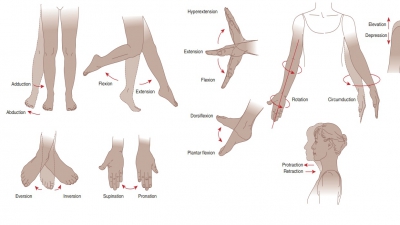

includes extension, flexion, hyperextension, abduction, adduction, and circumduction.

The following terms describe

types of angu-lar joint movements, with simple examples of each (FIGURE 8-7):

■■ Flexion: Bending parts at a

joint so they come closer together. It usually occurs along the sagittal plane,

decreasing the angle of the joint. For example, bending the trunk or the knee

from a straight to an angled position or bending the head forward toward the

chest.

■■ Extension: Moving a limb from

the midline of the body. The reverse of flexion, it occurs at the same joints

and also along the sagittal plane. The angle between the articulating bones is

increased. This usually straightens a flexed body part such as a limb. For

example, the straightening of a flexed elbow, neck, or knee.

■■ Hyperextension: Extending the

parts at a joint beyond the normal range of motion, often resulting in injury

because the anatomic position is exceeded.

■■ Dorsiflexion: Moving the ankle so the top of the foot comes closer to the shin or moving the wrist so the back of the hand comes closer to the arm (wrist extension).

■■ Plantar flexion: Moving the ankle

so the foot moves farther from the

shin, pointing the toes. This corresponds to wrist flexion.

■■ Abduction: Moving a part away

from the midline (longitudinal axis)

or median plane of the body. For example, when the arm or thigh is raised

lat-erally. For the toes or fingers, it means “spreading apart.” However, the

lateral bending of the trunk away from the body midline (in the frontal plane)

is not called abduction but lateral flexion.

■■ Adduction: Moving a part

toward the midline of the body. For the

toes or fingers, it is moving them toward the midline of the foot or hand. The

following joint movements are shown in FIGURE

8-8:

■■ Rotation: Moving a part around its axis, either directed toward the midline or away from it. It is common at the hip, shoulder, and the first two cervical vertebrae.

■■ Circumduction: Moving a part

so its end follows a circular path, as if describing a cone in space. The

distal end of a circumducting limb moves in a circle, whereas the “point” of

the cone (the hip or shoulder joint) remains nearly stationary. Circumduction

actually consists of the movements of flexion, then abduction, then extension,

and then adduction.

■■ Pronation: Turning the hand

so the palm is downward, facing posteriorly. The forearm is rotated medially,

moving the distal end of the radius across the ulna, forming an “X” between the

two bones. The forearm remains in this position when a person is standing but

relaxed. Pronation is not as strong a movement as supination.

■■ Supination: Turning the hand

so that the palm is upward, facing anteriorly. The forearm is rotated

laterally. In the anatomical position, the hand is supinated while the radius

and ulnae are parallel.

■■ Eversion: Turning the foot so

the plantar surface (sole) faces laterally.

■■ Inversion: Turning the foot

so the plantar surface faces medially.

■■ Protraction: Moving a part

forward, which is a nonangular anterior movement in the transverse plane. For

example, the mandible is protracted when you stick your jaw out.

■■ Retraction: Moving a part

backward, which is a nonangular posterior movement in the transverse plane. For

example, the mandible is retracted when you pull your jaw back after sticking

it out.

■■ Elevation: Raising a part

(lifting it superiorly). When you shrug your shoulders, the scapulae are

elevated.

■■ Depression: Lowering a part

(moving it inferiorly). When you chew, your mandible is elevated and depressed

repeatedly.

Another joint movement (not shown in Figure 8-8) is known as opposition. This involves the saddle joint between the trapezium and meta-carpal I. The thumb performs opposition when it is touched to the tips of the other fingers on the same hand. Opposition allows the hand to grab or hold an object. Reposition is the joint movement that returns the thumb and fingers from opposition. Basically, there are three general types of movements: angular, gliding, and rotation.

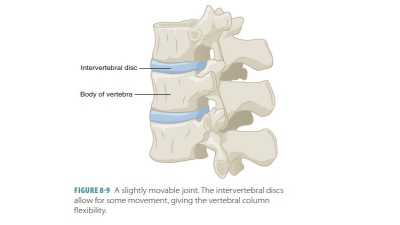

Gliding Movements

Gliding

movements occur when a flat (or

nearly flat) bone surface slips over or glides over another in a side to

side or back-and-forth motion. There is no major rotation or angulation. For

example, the movement of the intertarsal and intercarpal joints and between the

flat articular vertebral processes.

Rotation Movements

Rotation

movements involve the turning

of a bone around its long axis. This is common at the hip and shoulder

joints and is the singular movement allowed between the first two cervical

vertebrae. Rotation may be directed away from the midline or toward it. For

example, the thigh’s medial rotation and when the anterior surface of the femur

moves toward the body’s median plane. The opposite movement of medial rota-tion

is called lateral rotation.

1. Compare

axial with nonaxial movements.

2. Describe

angular and gliding movements.

3. Define

the terms flexion, extension, and dorsiflexion.