Divisions of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS)

| Home | | Anatomy and Physiology | | Anatomy and Physiology Health Education (APHE) |Chapter: Anatomy and Physiology for Health Professionals: Autonomic Nervous System (ANS)

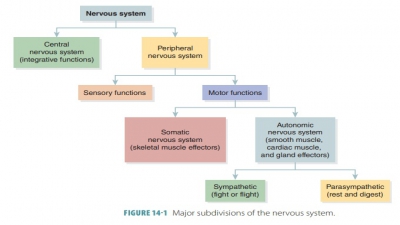

The ANS is divided into the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions.

Divisions of

the ANS

The ANS is divided into the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions. Certain visceral organs

have fibers from both divisions,

controlling the acti-vation or inhibition of their actions. The sympathetic

division prepares the body for stressful or emergency situations and is part

of the fight-or-flight respons. This division can change tissue and organ activities by releasing NE at

peripheral synapses and by distributing epinephrine and NE throughout the

body. Sympathetic activation, controlled by the

hypothalamus, occurs when the entire

sympathetic division responds to a crisis situation. When this happens, a

person feels extremely alert, energized, and euphoric. Blood pres-sure,

breathing, and heart rate increase; muscle tone is elevated; and energy

reserves are mobilized for action.

The parasympathetic division

functions in an opposite manner and is part of the rest-and-digest response.

When stress occurs, the sympathetic divi-sion increases heart and breathing

rates. As the stress subsides, the parasympathetic division decreases these

activities. Dual innervation is

applied so the two divi-sions counterbalance the effects of each other. This

utilizes cardiac, pulmonary, esophageal,

celiac, inferior mesenteric, and hypogastric plexuses. Sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers that reach the

heart and lungs pass through the cardiac plexus. Parasympathetic activation is

signified by constricted pupils for better

focusing, increased glandular secretions, raised nutri-ent absorption, and

changes in blood flow that are associated with sexual arousal. In the digestive

tract, smooth muscle activity increases, defecation is stim-ulated, the urinary

bladder contracts, and respiration and heart rate are reduced.

A little-known third division of

the ANS is known as the enteric

nervous system (ENS). It is a network of neurons and

nerve networks in the digestive tract and is influenced by both the sympathetic

and para-sympathetic divisions. The ENS is primarily related to the visceral

reflexes, and has about 100 million neurons and uses all of the

neurotransmitters found in the brain.

Most of the time, the sympathetic

and parasympa-thetic divisions of the ANS have opposite effects such as

excitation versus inhibition. However, these divi-sions may also be

independent, with only one of them innervating certain body structures. They

also may work together and each may control just one stage of a complicated

series of actions. Basically, the sympa-thetic division activates during

emergencies, stress, or exertion, while the parasympathetic division activates

when the body is at rest.

Sympathetic Division

The sympathetic division’s

functions include increased heart rate and respiration, reduced salivation,

clammy skin, and dilation of eye pupils. Mental alertness is dramatically

increased as is the metabolic rate. During physical activity, it constricts

visceral blood vessels and sometimes constricts cutaneous blood vessels. Blood

is moved to active skeletal muscles and the heart, and blood pressure

increases. The sweat glands are activated. Lung bronchioles are dilated,

resulting in increases in ventilation, moving more oxygen to body cells. The

liver releases more glucose into the blood to supply energy to the body.

Simultaneously, it slows down nonessential activities such as motility in the

gastrointestinal tract and the urinary system. The sympathetic division may be

referred to as the “E division” (signifying exercise, emergency, and

excitement).

Parasympathetic Division

The parasympathetic division

keeps energy use by the body to its lowest possible amounts. It controls

digestion of food and elimination of feces and urine. This division stimulates

visceral activity, decreases the metabolic rate, increases salivary and

digestive secre-tions, and increases digestive motility and blood flow. During

digestion, blood pressure and heart rate are lowered while the gastrointestinal

system is active. Also, the pupils of the eyes become constricted and the

lenses are accommodated for close vision. The parasympathetic division may be

referred to as the “D division” (signifying digestion, defecation, and

diuresis). Both divisions antagonize each other’s effects greatly to maintain

homeostasis.

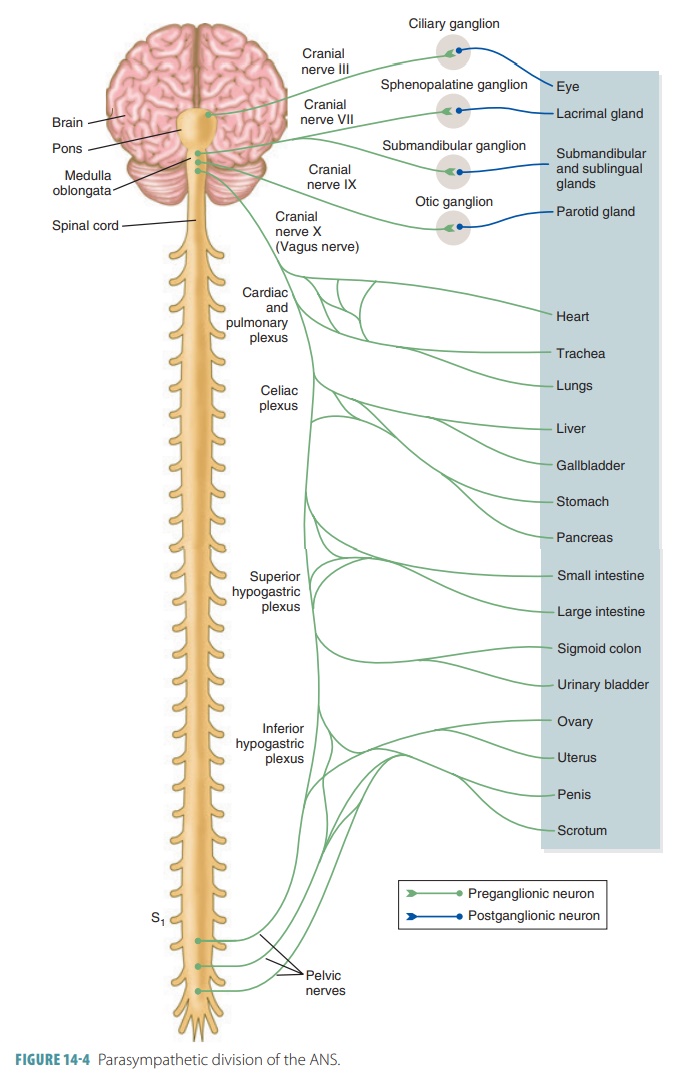

Parasympathetic fibers are

craniosacral, originat-ing in the brain and sacral spinal cord (FIGURE 14-4). They

have long preganglionic and short postganglionic fibers. Parasympathetic

ganglia are mostly located in the visceral effector organs. Overall, the

parasympa-thetic division is simpler than the sympathetic division. It is also

known as the craniosacral division

because its preganglionic fibers emerge from opposite ends of the CNS (the

brain stem and sacral spinal cord). The preganglionic axons run from the CNS,

nearly all the way to the innervated target structures. At these points, axons

synapse with postganglionic neurons of the terminal

ganglia, lying close to or

inside the target organs. Extremely short postganglionic axons emerge from the

terminal ganglia, synapsing with nearby effec-tor cells. In the cranial portion

of the parasympathetic nervous system, preganglionic fibers exist in the facial,

oculomotor, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves. Cell bodies of these fibers lie

in related motor cranial nerve nuclei of the brain stem.

Oculomotor Nerves

The parasympathetic fibers of the

oculomotor (III) nerves innervate smooth muscles that cause the pupils of the eyes to constrict and the lenses to bulge, which are

both used when focusing. Cell bodies of the postganglionic neurons lie in the ciliary ganglia inside

the eye orbits.

Facial Nerves

The parasympathetic fibers of the

facial (VII) nerves stimulate large

glands located in the head. Pregangli-onic fibers synapse with postganglionic

neurons in the pterygopalatine

ganglia, which are just

posterior to the maxillae. Preganglionic neurons stimulating sali-vary

glands (submandibular and sublingual) synapse with postganglionic neurons in

the submandibular ganglia.

Glossopharyngeal Nerves

The parasympathetic fibers of the

glossopharyngeal (IX) nerves begin in the inferior salivary nuclei of the medulla. They synapse in the otic ganglia just

infe-rior to the foramen ovale of the skull. The glossopha-ryngeal nerves

innervate the parotid salivary glands.

Vagus Nerves

The two vagus (X) nerves make up between 80% and 90% of the parasympathetic

outflow fibers in the body. Their preganglionic axons begin primarily in the

dor-sal motor nuclei of the medulla. They synapse in termi-nal ganglia that are

mostly located in the target organ walls. Branches of the vagus nerves pass to

the cardiac plexuses, which supply fibers to the heart that slow the heart rate. Other

branches supply the pulmonary plexuses serving the lungs and the

esophageal plexuses serving the

esophagus. Near the esophagus, the main trunks of the vagus nerves join fibers to form anterior and posterior vagal trunks, each with fibers from both vagus nerves. The trunk continues down to the abdominal

cavity, sending fibers through the large abdominal

aortic plexus, which is made up of the celiac, superior mesenteric, and

hypogastric plexuses running along the aorta. The large abdominal aortic plexus

then branches off to the abdominal viscera. The celiac ganglion innervates the

smooth muscles of the stomach, small intestine, liver, pancreas, and the

ascending half of the transverse colon.

The sacral portion of the

parasympathetic division serves the pelvic organs and the distal half of the

large intestine. It arises from the lateral gray matter neurons of the spinal

cord segments S2 to S4. Axons of these neurons continue

through the ventral roots of the spinal nerves to the ventral rami. They branch

to form the pelvic splanchnic nerves that pass through the

inferior hypogastric (pelvic) plexus in the floor of the pelvis.

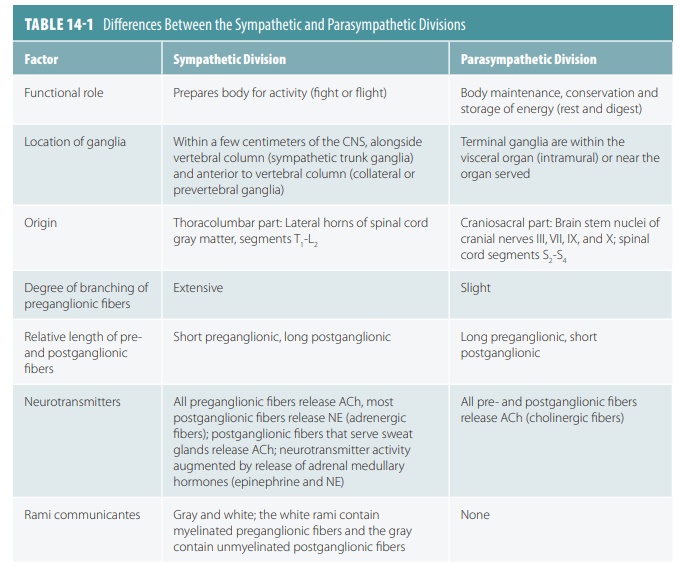

Splanchnic nerves carry fibers that

synapse in collateral ganglia. TABLE 14-1 compares

differences between the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions.

1. Identify the roles of the

sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

2. Define the terms “terminal

ganglia” and “lateral horns.”

3. Explain what may occur

with preganglionic and postganglionic neurons when a preganglionic axon reaches

a trunk ganglion.

Related Topics