Heat Sterilization - Sterilization Methods

| Home | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology |Chapter: Pharmaceutical Microbiology : Sterilization Procedures And Sterility Assurance

Heat is the most reliable and widely used means of sterilization, affording its antimicrobial activity through destruction of enzymes and other essential cell constituents.

HEAT STERILIZATION

Heat is the most reliable and widely used means of sterilization,

affording its antimicrobial activity through destruction of enzymes and other

essential cell constituents. These lethal events proceed most rapidly in a

fully hydrated state, thus requiring a lower heat input (temperature and time)

under conditions of high humidity where denaturation and hydrolysis reactions

predominate, rather than in the dry state where oxidative changes take place.

This method of sterilization is limited to thermostable products, but can be

applied to both moisture-sensitive and moisture-resistant items for which dry

(160–180 °C) and moist (121–134 °C) heat sterilization procedures are

respectively used. Where thermal degradation of a product might possibly occur,

it can usually be minimized by selecting the higher temperature range, as the

shorter exposure times employed generally result in a lower fractional

degradation.

Sterilization Processes

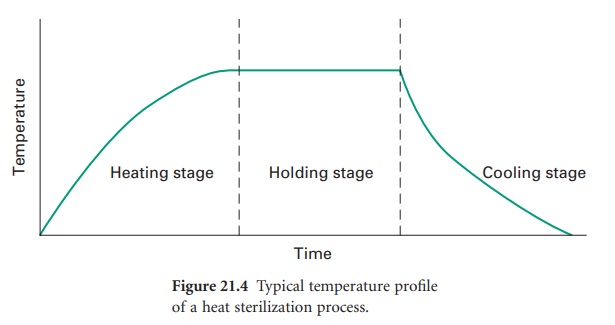

In any heat sterilization process, the

articles to be treated must first be raised to sterilization temperature and

this involves a heating-up stage. In the traditional approach, timing for the

process (the holding time) then begins. It has been recognized, however, that

during both the heating-up and cooling-down stages of a sterilization cycle (Figure 21.4),

the product is held at an elevated temperature and these stages may thus

contribute to the overall biocidal potential of the process.

A method has been devised to convert all

the temperature–time combinations occurring during the heating, sterilizing and

cooling stages of a moist heat (steam) sterilization cycle to the equivalent

time at 121 °C. This involves following the temperature profile of a load,

integrating the heat input (as a measure of lethality), and converting it to

the equivalent time at the standard temperature of 121 °C. Using this approach,

the overall lethality of any process can be deduced and is defined as the F-value; this expresses heat treatment at any temperature

as equal to that of a certain number of minutes at 121 °C. In other words, if a

moist heat sterilization process has an F-value of x, then it has the same lethal effect on a given

organism as heating at 121 °C for x minutes,

irrespective of the actual temperature employed or of any fluctuations in the

heating process due to heating and cooling stages. The F-value of a process will vary according to the moist

heat resistance of the reference organism; when the reference spore is that

of B. stearothermophilus with a Z-value of 10 °C, then the F-value is known as the F 0-value.

A relationship between F-and D-values, leading to

an assessment of the probable number of survivors in a load following heat

treatment, can be established from the following equation: where D is the D-value at 121 °C,

and N 0 and N represent,

respectively, the initial and final number of viable cells per unit volume.

![]()

The F-concept has

evolved from the food industry and principally relates to the sterilization of

articles by moist heat. Because it permits calculation of the extent to which

the heating and cooling phases contribute to the overall killing effect of the

autoclaving cycle, the F-concept enables a

sterilization process to be individually developed for a particular product.

This means that adequate sterility assurance can be achieved in autoclaving

cycles in which the traditional pharmacopoeial recommendation of 15 minutes at

121 °C is not achieved. The holding time may be reduced below 15 minutes if

there is a substantial killing effect during the heating and cooling phases,

and an adequate cycle can be achieved even if the ‘target ’ temperature of 121

°C is not reached. Thus, F-values offer both

a means by which alternative sterilizing cycles can be compared in terms of

their microbial killing efficiency, and a mechanism by which over-processing of

marginally thermolabile products can be reduced without compromising sterility

assurance. The European Pharmacopoeia emphasizes

that when a steam sterilization cycle is designed on the basis of F 0 data, it

may be necessary to perform continuous and rigorous microbiological monitoring

of the bioburden during routine manufacturing in order consistently to achieve

an acceptable sterility assurance level.

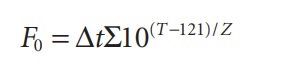

F 0 values may be calculated either from the area under the curve of a plot of autoclave temperature against time constructed using special chart paper on which the temperature scale is modified to take into account the progressively greater lethality of higher temperatures, or by use of the equation:

where Δ t is the time

interval between temperature measurements, T is the

product temperature at time t, and Z is (assumed to be) 10 °C.

Thus, if temperatures were being

recorded from a thermocouple at 1.00 minute intervals then Δ t 1.00, and a temperature of, for example, 115 °C

maintained for 1 minute would give an F 0 value of 1 minute × 10 (115–121)/10, which is

equal to 0.25 minutes. In practice, such calculations could easily be performed

on the data from several thermocouples within an autoclave using suitable

software, and, in a manufacturing situation, these would be part of the batch

records. Application of the F-value concept has

been largely restricted to steam sterilization processes, although there is a

less frequently employed, but direct parallel in dry heat sterilization

Moist heat has been recognized as an efficient biocidal agent from the

early days of bacteriology, when it was principally developed for the

sterilization of culture media. It now finds widespread application in the

processing of many thermostable products and devices. In the pharmaceutical and

medical sphere it is used in the sterilization of dressings, sheets, surgical

and diagnostic equipment, containers and closures, and aqueous injections,

ophthalmic preparations and irrigation fluids, in addition to the processing of

soiled and contaminated items.

Sterilization by moist heat usually involves the use of steam at temperatures in the range 121–134 °C, and while alternative strategies are available for the processing of products unstable at these high temperatures, they rarely offer the same degree of sterility assurance and should be avoided if at all possible. The elevated temperatures generally associated with moist heat sterilization methods can only be achieved by the generation of steam under pressure.

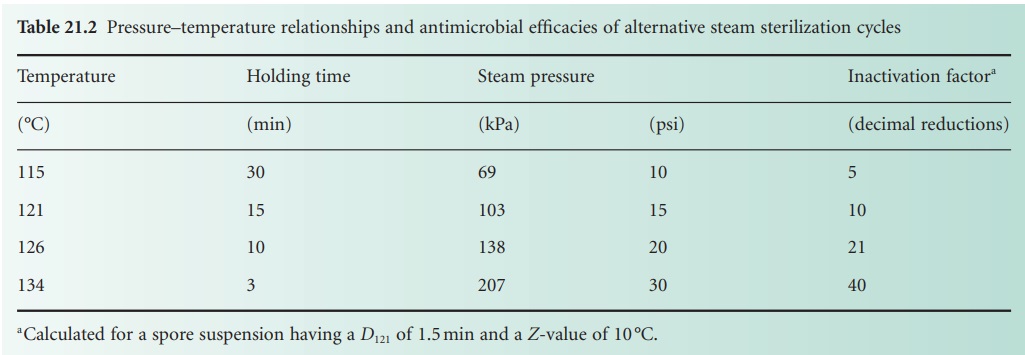

By far the most commonly employed standard temperature/time cycles for bottled fluids and porous loads (e.g. surgical dressings) are 121 °C for 15 minutes and 134 °C for 3 minutes, respectively. Not only do high-temperature–short time cycles often result in lower fractional degradation, they also afford the advantage of achieving higher levels of sterility assurance due to greater inactivation factors (Table 21.2). Before the publication of the 1988 British Pharmacopoeia the 115 °C for 30 minute cycle was considered an acceptable alternative to 121 °C for 15 minutes, but it is no longer considered sufficient to give the desired sterility assurance levels for products which may contain significant concentrations of thermophilic spores.

i) Steam as a sterilizing agent

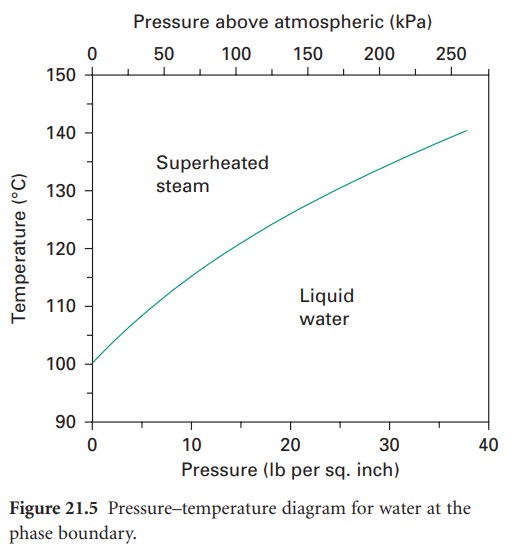

To act as an efficient sterilizing

agent, steam should be able to provide moisture and heat efficiently to the

article to be sterilized. This is most effectively done using saturated steam,

which is steam in thermal equilibrium with the water from which it is derived,

i.e. steam on the phase boundary (Figure 21.5).

Under these circumstances, contact with a cooler surface causes condensation

and contraction, drawing in fresh steam and leading to the immediate release of

the latent heat, which represents approximately 80% of the total heat energy.

In this way, heat and moisture are imparted rapidly to articles being

sterilized and dry porous loads are quickly penetrated by the steam.

Steam for sterilization can either be generated within the sterilizer,

as with portable bench or ‘instrument and utensil ’ sterilizers, in which case

it is constantly in contact with water and is known as ‘wet ’ steam, or can be

supplied under pressure (350–400 kPa) from a separate boiler as ‘dry ’

saturated steam with no entrained water droplets. The killing potential of ‘wet’

steam is the same as that of ‘dry’ saturated steam at the same temperature, but

it is more likely to soak a porous load, creating physical difficulties for

further steam penetration. Thus, major industrial and hospital sterilizers are

usually supplied with ‘dry’ saturated steam and attention is paid to the removal

of entrained water droplets within the supply line to prevent introduction of a

water ‘fog’ into the sterilizer.

If the temperature of ‘dry ’ saturated

steam is increased, then, in the absence of entrained moisture, the relative

humidity or degree of saturation is reduced and the steam becomes superheated (Figure 21.5).

During sterilization this can arise in a number of ways, for example by overheating

the steam-jacket, by using too dry a steam supply, by excessive pressure

reduction during passage of steam from the boiler to the sterilizer chamber,

and by evolution of heat of hydration when steaming overdried cotton fabrics.

Superheated steam behaves in the same manner as hot air as condensation and

release of latent heat will not occur unless the steam is cooled to the phase

boundary temperature. Thus, it proves to be an inefficient sterilizing agent

and, although a small degree of transient superheating can be tolerated, a

maximum acceptable level of 5 °C superheat is set, i.e. the temperature of the

steam is never greater than 5 °C above the phase boundary temperature at that

pressure.

The relationship between temperature and pressure holds true only in the

presence of pure steam; adulteration with air contributes to a partial pressure

but not to the temperature of the steam. Thus, in the presence of air the

temperature achieved will reflect the contribution made by the steam and will

be lower than that normally attributed to the total pressure recorded. Addition

of further steam will raise the temperature but residual air surrounding

articles may delay heat penetration or, if a large amount of air is present, it

may collect at the bottom of the sterilizer, completely altering the

temperature profile of the sterilizer chamber. It is for these reasons that

efficient air removal is a major aim in the design and operation of a

boiler-fed steam sterilizer.

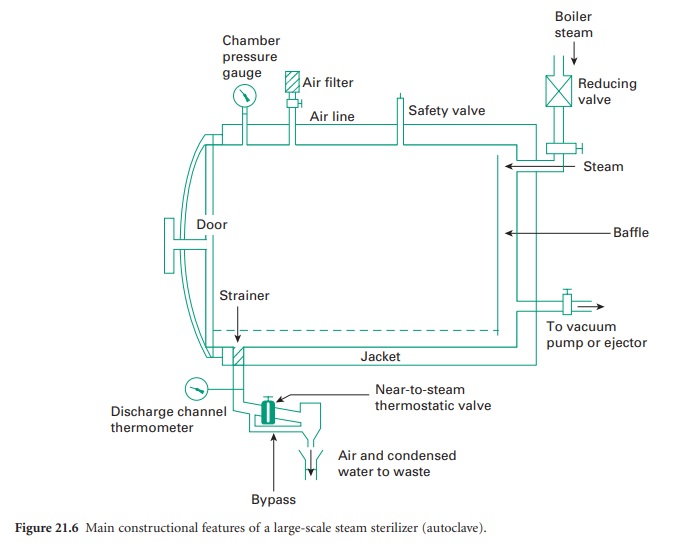

ii) Sterilizer design and

operation

Steam sterilizers, or autoclaves as they are also known, are stainless

steel vessels designed to withstand the steam pressures employed in

sterilization. They can be: ‘portable ’ sterilizers, which generally have

internal electric heaters to produce steam and are used for small pilot or

laboratory-scale sterilization and for the treatment of instruments and

utensils; or large-scale sterilizers for routine hospital or industrial use, operating

on ‘dry ’ saturated steam from a separate boiler (Figure 21.6).

Because of their widespread use within pharmacy this latter type will be

considered in greatest detail.

There are two main types of large sterilizers, those designed for use

with porous loads (i.e. dressings) and generally operated at a minimum

temperature of 134 °C, and those designed as bottled fluid sterilizers employing

a minimum temperature of 121 °C. The stages of operation are common to both and

can be summarized as air removal and steam admission, heating-up and exposure,

and drying or cooling. Many modifications of design exist and in this section

only general features will be considered. Fuller treatments of sterilizer

design and operation can be found in the relevant Department of Health

technical memorandums (DH 1995, DH 1997).

General Design Features

Steam sterilizers are constructed with either cylindrical or rectangular

chambers, with preferred capacities ranging from 400 to 800 L. They can be

sealed by either a single door or by doors at both ends (to allow

through-passage of processed materials). During sterilization the doors are

held closed by a locking mechanism which prevents opening when the chamber is

under pressure and until the chamber has cooled to a preset temperature,

typically 80 °C.

In the larger sterilizers the chamber may be surround ed by a steam

jacket which can be used to heat the autoclave chamber and promote a more

uniform temperature throughout the load. The same jacket can also be filled

with water at the end of the cycle to facilitate cooling and thus reduce the

overall cycle time. The chamber floor slopes towards a discharge channel

through which air and condensate can be removed. Temperature is monitored

within the opening of the discharge channel and by thermocouples in dummy

packages; jacket and chamber pressures are followed using pressure gauges. In

hospitals and industry, it is common practice to operate sterilizers on an

automatic cycle, each stage of operation being controlled by a timer responding

to temperature-or pressure-sensing devices.

The stages of operation are as follows.

1. Air removal and steam admission.

Air can be removed from steam

sterilizers either by downward displacement with steam, evacuation or a

combination of the two. In the downward displacement sterilizer, the heavier

cool air is forced out of the discharge channel by incoming hot steam. This has

the benefit of warming the load during air removal, which aids the heating-up process.

It finds widest application in the sterilization of bottled fluids where bottle

breakage may occur under the combined stresses of evacuation and high temperature.

For more air-retentive loads (i.e. dressings), however, this technique of air

removal is unsatisfactory and mechanical evacuation of the air is essential

before admission of the steam. This can either be to an extremely high level

(e.g.2.5 kPa) or can involve a period of pulsed evacuation and steam admission,

the latter approach improving air extraction from dressings packs. After

evacuation, steam penetration into the load is very rapid and heating-up is

almost instantaneous. It is axiomatic that packaging and loading of articles

within a sterilizer be so organized as to facilitate air removal.

During the sterilization process, small pockets of entrained air may

still be released, especially from packages, and this air must be removed. This

is achieved in a porous load autoclave with a near-to-steam thermostatic valve

incorporated in the discharge channel. The valve operates on the principle of

an expandable bellows containing a volatile liquid which vaporizes at the

temperature of saturated steam thereby closing the valve, and condenses on the

passage of a cooler air-steam mixture, thus reopening the valve and discharging

the air. Condensate generated during the sterilization process can also be

removed by this device. Small quantities of air will not, however, lower the

temperature sufficiently to operate the valve and so a continual slight flow of

steam is maintained through a bypass around the device in order to flush away

residual air.

It is common practice to package sterile fluids, especially intravenous

fluids, in flexible plastic containers. During sterilization these can develop

a considerable internal pressure in the airspace above the fluid and it is

therefore necessary to maintain a proportion of air within the sterilizing

chamber to produce sufficient overpressure to prevent these containers from

bursting (air ballasting). In sterilizers modified or designed to process this

type of product, air removal is therefore unnecessary but special attention

must be paid to the prevention of air ‘layering’ within the chamber. This is

overcome by the inclusion of a fan or through a continuous spray of hot water

within the chamber to mix the air and steam. Air ballasting can also be

employed to prevent bottle breakage.

2. Heating-up

and exposure.

When the sterilizer reaches its

operating temperature and pressure the sterilization stage begins. The duration

of exposure may include a heating-up time in addition to the holding time and

this will normally be established using thermocouples in dummy articles.

3.

Drying or cooling.

Dressings packs and other porous loads

may become dampened during the sterilization process and must be dried before

removal from the chamber. This is achieved by steam exhaust and application of

a vacuum, often assisted by heat from the steam-filled jacket if fitted. After

drying, atmospheric pressure within the chamber is restored by admission of

sterile filtered air.

For bottled fluids the final stage of the sterilization process is

cooling, and this needs to be achieved as rapidly as possible to minimize

thermal degradation of the product and to reduce processing time. In modem

sterilizers, this is achieved by circulating water in the jacket that surrounds

the chamber or by spray-cooling with retained condensate delivered to the surface

of the load by nozzles fitted into the roof of the sterilizer chamber. This is

often accompanied by the introduction of filtered, compressed air to minimize

container breakage due to high internal pressures (air ballasting). Containers

must not be removed from the sterilizer until the internal pressure has dropped

to a safe level, usually indicated by a temperature of less than 80 °C.

Occasionally, spray-cooling water may be a source of bacterial contamination

and its microbiological quality must be carefully monitored.

B) Dry Heat Sterilization

The lethal effects of dry heat on microorganisms are due largely to

oxidative processes, which are less effective than the hydrolytic damage which

results from exposure to steam. Thus, dry heat sterilization usually employs

higher temperatures in the range 160–180 °C and requires exposure times of up

to 2 hours depending on the temperature employed.

Again, bacterial spores are much more resistant than vegetative cells

and their recorded resistance varies markedly depending on their degree of

dryness. In many early studies on dry heat resistance of spores their water

content was not adequately controlled, so conflicting data arose regarding the

exposure conditions necessary to achieve effective sterilization. This was

partly responsible for variations in recommended exposure temperatures and

times in different pharmacopoeias.

Dry heat application is generally restricted to glassware and metal

surgical instruments (where its good penetrability and non-corrosive nature are

of benefit), non-aqueous thermostable liquids and thermostable powders. In practice,

the range of materials that are actually subjected to dry heat sterilization is

quite limited, and consists largely of items used in hospitals. The major

industrial application is in the sterilization of glass bottles which are to be

filled aseptically, and here the attraction of the process is that it not only

achieves an adequate sterility assurance level, but that it may also destroy

bacterial endotoxins (products of Gram-negative bacteria, also known as

pyrogens, that cause fever when injected into the body). These are difficult to

eliminate by other means. For the purposes of de-pyrogenation of glass,

temperatures of approximately 250 °C are used.

The F-value concept that

was developed for steam sterilization processes has an equivalent in dry heat

sterilization although its application has been limited. The FH designation describes the lethality of a dry heat

process in terms of the equivalent number of minutes exposure at 170 °C, and in

this case a Z-value of 20 °C has been found

empirically to be appropriate for calculation purposes; this contrasts with the

value of 10 °C which is typically employed to describe moist heat resistance.

i) Sterilizer design

Dry heat sterilization is usually carried out in a hot-air oven which

comprises an insulated polished stainless steel chamber, with a usual capacity

of up to 250 L, surrounded by an outer case containing electric heaters located

in positions to prevent cool spots developing inside the chamber. A fan is

fitted to the rear of the oven to provide circulating air, thus ensuring more

rapid equilibration of temperature. Shelves within the chamber are perforated

to allow good airflow. Thermocouples can be used to monitor the temperature of

both the oven air and articles contained within. A fixed temperature sensor

connected to a chart or digital recorder provides a permanent record of the

sterilization cycle. Appropriate door-locking controls should be incorporated

to prevent interruption of a sterilization cycle once begun.

Recent sterilizer developments have led to the use of dry heat

sterilizing tunnels where heat transfer is achieved by infrared irradiation or

by forced convection in filtered laminar airflow tunnels. Items to be

sterilized are placed on a conveyer belt and pass through a high-temperature

zone (250–300 + °C) over a period of several minutes.

ii) Sterilizer operation

Articles to be sterilized must be wrapped or enclosed in containers of

sufficient strength and integrity to provide good post-sterilization protection

against contamination. Suitable materials are paper, cardboard tubes or

aluminium containers. Container shape and design must be such that heat

penetration is encouraged in order to shorten the heating-up stage; this can be

achieved by using narrow containers with dull, non-reflecting surfaces. In a

hot-air oven, heat is delivered to articles principally by radiation and

convection; thus, they must be carefully arranged within the chamber to avoid

obscuring centrally placed articles from wall radiation or impending air flow.

The temperature variation within the chamber should not exceed ± 5 °C of the

recorded temperature. Heating-up times, which may be as long as 4 hours for

articles with poor heat-conducting properties, can be reduced by preheating the

oven before loading. Following sterilization, the chamber temperature is

usually allowed to fall to around 40 °C before removal of sterilized articles;

this can be accelerated by the use of forced cooling with filtered air.

Related Topics