Introduction to Metabolism

| Home | | Biochemistry |Chapter: Biochemistry : Introduction to Metabolism and Glycolysis

Individual enzymic reactions were analyzed in an effort to explain the mechanisms of catalysis.

INTRODUCTION TO METABOLISM

In Chapter 5,

individual enzymic reactions were analyzed in an effort to explain the

mechanisms of catalysis. However, in cells, these reactions rarely occur in

isolation but, rather, are organized into multistep sequences called pathways,

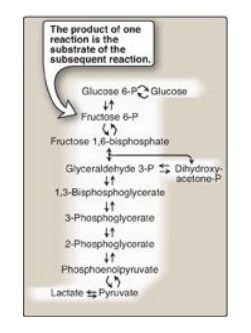

such as that of glycolysis (Figure 8.1). In a pathway, the product of one

reaction serves as the substrate of the subsequent reaction. Different pathways

can also intersect, forming an integrated and purposeful network of chemical

reactions. These are collectively called metabolism, which is the sum of all

the chemical changes occurring in a cell, a tissue, or the body. Most pathways

can be classified as either catabolic (degradative) or anabolic (synthetic).

Catabolic reactions break down complex molecules, such as proteins,

polysaccharides, and lipids, to a few simple molecules (for example, CO2,

NH3 [ammonia], and H2O). Anabolic pathways form complex

end products from simple precursors, for example, the synthesis of the

polysaccharide, glycogen, from glucose. [Note: Pathways that regenerate a

component are called cycles.] In the following chapters, this text focuses on

the central metabolic pathways that are involved in synthesizing and degrading

carbohydrates, lipids, and amino acids.

Figure 8.1 Glycolysis, an

example of ametabolic pathway. [Note: Pyruvate to phosphoenolpyruvate requires

two reactions.] Curved reaction arrows  indicate forward and

reverse reactions that are catalyzed by different enzymes. P = phosphate.

indicate forward and

reverse reactions that are catalyzed by different enzymes. P = phosphate.

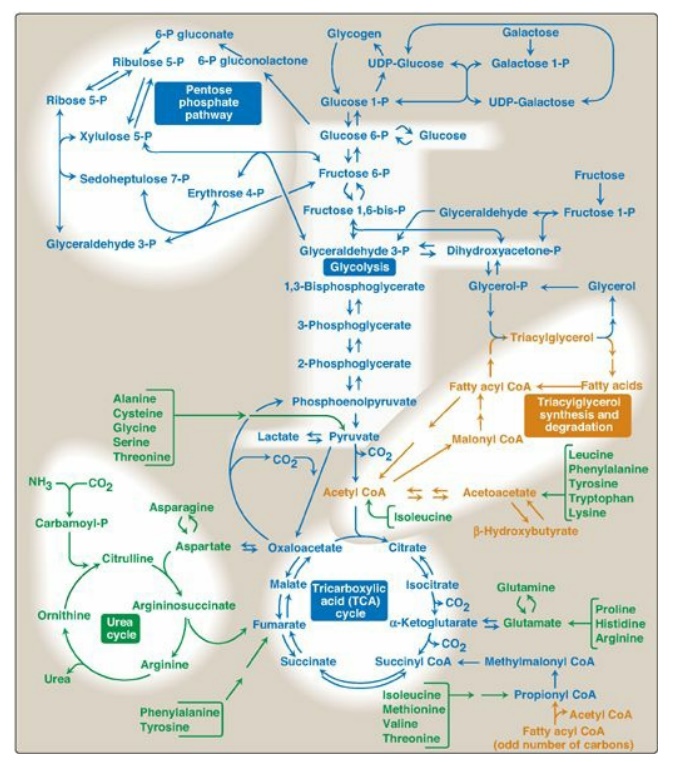

A. Metabolic map

It is convenient to investigate metabolism by examining its component pathways. Each pathway is composed of multienzyme sequences, and each enzyme, in turn, may exhibit important catalytic or regulatory features. To provide the reader with the “big picture,” a metabolic map containing the important central pathways of energy metabolism is presented in Figure 8.2. This map is useful in tracing connections between pathways, visualizing the purposeful “movement” of metabolic intermediates, and depicting the effect on the flow of intermediates if a pathway is blocked (for example, by a drug or an inherited deficiency of an enzyme). Throughout the next three units of this book, each pathway under discussion will be repeatedly featured as part of the major metabolic map shown in Figure 8.2.

Figure 8.2 Important reactions of intermediary metabolism. Several important pathways to be discussed in later chapters are highlighted. Curved reaction arrows  indicate forward and reverse reactions that are catalyzed by different enzymes. The straight arrows

indicate forward and reverse reactions that are catalyzed by different enzymes. The straight arrows  indicate forward and reverse reactions that are catalyzed by the same enzyme. Blue text = intermediates of carbohydrate metabolism; brown text = intermediates of lipid metabolism; green text = intermediates of protein metabolism. UDP = uridine diphosphate; P = phosphate; CoA = coenzyme A.

indicate forward and reverse reactions that are catalyzed by the same enzyme. Blue text = intermediates of carbohydrate metabolism; brown text = intermediates of lipid metabolism; green text = intermediates of protein metabolism. UDP = uridine diphosphate; P = phosphate; CoA = coenzyme A.

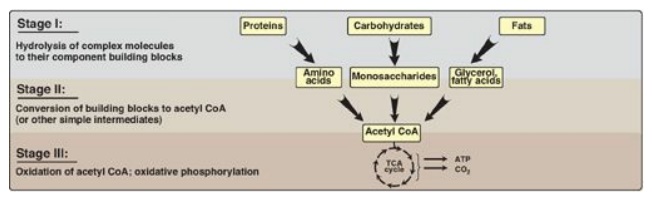

B. Catabolic pathways

Catabolic reactions

serve to capture chemical energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

from the degradation of energy-rich fuel molecules. Catabolism also allows

molecules in the diet (or nutrient molecules stored in cells) to be converted

into building blocks needed for the synthesis of complex molecules. Energy

generation by degradation of complex molecules occurs in three stages as shown

in Figure 8.3. [Note: Catabolic pathways are typically oxidative, and require

oxidized coenzymes such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+).]

Figure 8.3 Three stages of

catabolism. CoA = coenzyme A; TCA = tricarboxylic acid.

1. Hydrolysis of complex molecules: In the first stage, complex

molecules are broken down into their component building blocks. For example,

proteins are degraded to amino acids, polysaccharides to monosaccharides, and

fats (triacylglycerols) to free fatty acids and glycerol.

2. Conversion of building blocks to simple

intermediates: In

the second stage, these diverse building blocks are further degraded to acetyl

coenzyme A (CoA) and a few other simple molecules. Some energy is captured as

ATP, but the amount is small compared with the energy produced during the third

stage of catabolism.

3. Oxidation of acetyl coenzyme A: The tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle

is the final common pathway in the oxidation of fuel molecules that produce

acetyl CoA. Oxidation of acetyl CoA generates large amounts of ATP via

oxidative phosphorylation as electrons flow from NADH and flavin adenine

dinucleotide (FADH2) to oxygen.

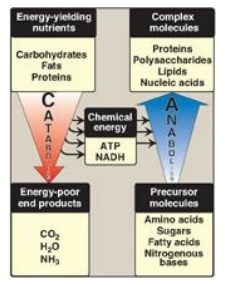

C. Anabolic pathways

Anabolic reactions

combine small molecules, such as amino acids, to form complex molecules such as

proteins (Figure 8.4). Anabolic reactions require energy (are endergonic),

which is generally provided by the hydrolysis of ATP to adenosine diphosphate

(ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). Anabolic reactions often involve chemical

reductions in which the reducing power is most frequently provided by the

electron donor NADPH. Note that catabolism is a convergent process (that is, a

wide variety of molecules are transformed into a few common end products). By

contrast, anabolism is a divergent process in which a few biosynthetic

precursors form a wide variety of polymeric, or complex, products.

Figure 8.4 Comparison of

catabolic and anabolic pathways. ATP = adenosine triphosphate; NADH =

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide.

Related Topics