OverView of Intensive Medicines Monitoring Programme Methodology

| Home | | Pharmacovigilance |Chapter: Pharmacovigilance: PEM in New Zealand

The core methodology of the IMMP – prospective observational cohort studies on selected medicines – remains very similar, and reviews of the IMMP meth-ods have been published (Coulter, 1998, 2000; Clark and Harrison-Woolrych, 2006).

OVER-VIEW OF INTENSIVE MEDICINES

MONITORING PROGRAMME METHODOLOGY

The

core methodology of the IMMP – prospective observational cohort studies on

selected medicines – remains very similar, and reviews of the IMMP meth-ods

have been published (Coulter, 1998, 2000; Clark and Harrison-Woolrych, 2006).

Essentially, exposure data are obtained by establishing cohorts of patients

prescribed the monitored medicine, and outcome data are obtained by identifying

clinical events at various time points after the medicine was prescribed.

Since

its inception as the first PEM programme in the world, the IMMP methodology has

developed considerably and has become much more comprehen-sive. This chapter

describes and illustrates the method-ology, with reference to new developments

and with emphasis on those features that are unique to the NZ IMMP.

ESTABLISHING THE COHORTS

The

IMMP cohorts are established using identifi-able patients from prescription

records supplied by community and hospital pharmacies throughout NZ. All

pharmacies in NZ maintain electronic prescrip-tion records and computer

software programs flag IMMP medicines. Thus printouts of all prescriptions

dispensed for IMMP medicines can be produced, and these are sent (Freepost) to

the IMMP every 4 months on request.

In

NZ to date, it has been necessary to use dispens-ing pharmacies as the source

of medicine usage. In the UK, the Drug Safety Research Unit obtains the

prescription data from a central source, the Prescrip-tion Pricing Division

(Chapter 24). There is no equivalent database in NZ – there are centralized

records of subsidized medicines, but new medicines are not usually subsidized

in the first year after licens-ing, and some medicines never become subsidized,

even though they may be widely used.

Pharmacists’

provision of data to the IMMP is voluntary and unpaid, although the NZ

Pharmaceuti-cal Council’s Code of Ethics requires pharmacists to participate in

the programme. Compliance with return-ing the prescription reports has always

been extremely high (currently greater than 90%), and the direct rela-tionships

established with pharmacists are valuable in providing additional prescribing

information and further reports of adverse events. Many pharmacists also

provide professional input by commenting on usage trends, which alert to

problems of tolerance, inefficacy, medication error, misuse or abuse.

DURATION OF PRESCRIPTION DATA COLLECTION

All

prescriptions for the monitored medicine during the period of monitoring

(historical mean 58 months) are recorded, providing a prescribing history for

each patient for as long as treatment continues. This is another difference to

the UK system of PEM, where medicines are usually monitored for an average time

of 6 months after first prescription (Chapter 24). The longer duration of

monitoring in NZ provides greater opportunity for identifying (a) delayed

effects, use in pregnancy or lactation, (c) death rates and causes of death,

(d) reasons for the cessation of ther-apy, (e) changed indications (these

frequently broaden over time), (f) evidence of tolerance or dependence, changes

in prescribing practice which for new medicines takes time to be established

and (h) changes in patient characteristics which in the early post-marketing

phase of a drug frequently differ from later use.

COHORT SIZE

The

desirable size for a cohort is around 10 000 patients (Inman, 1981a). For 22

medicines where monitor-ing was completed, mean cohort size was 10 964

patients, and the mean duration of monitoring was 58 months. However, for some

medicines – e.g. enta-capone – it has been difficult to establish cohorts of

sufficient size in a reasonable time frame. This is sometimes due to the small

population of NZ (about 4 million) but may also be due to other factors,

includ-ing which medicines are subsidized for use. This said lack of government

subsidization has not always limited use – none of the cyclo-oxygenase (COX) II

inhibitor medicines were ever subsidized, and yet the cohorts for rofecoxib

plus celecoxib grew to around 60 000 patients in 1 year (Harrison-Woolrych et al., 2005).

It is sometimes necessary to establish cohorts larger than 10 000 patients. Prescription data for the obesity medicine sibutramine showed that the duration of treatment for the majority of patients was less than 3 months, and thus greater numbers were needed to increase the patient-years of exposure to the medicine.

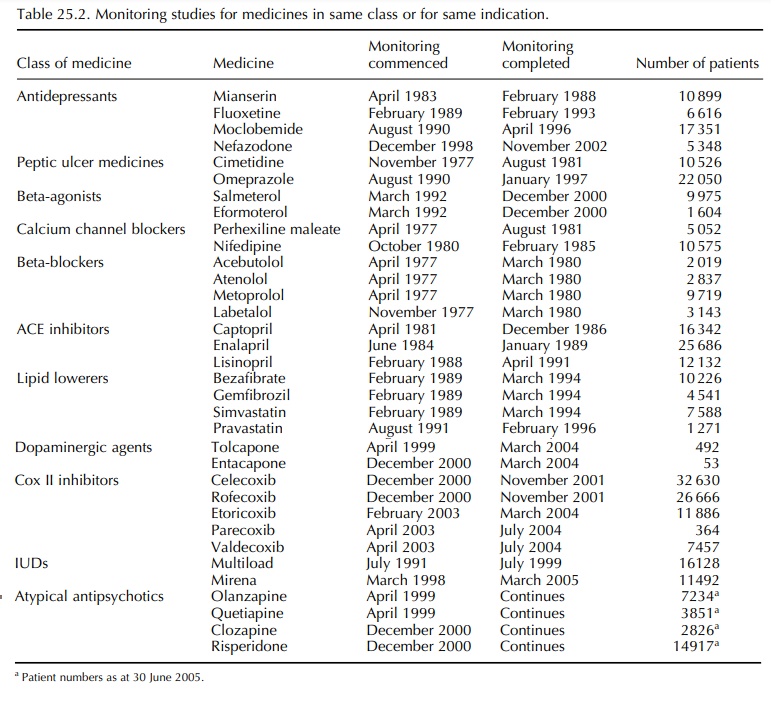

COMPARATORS

For

several medicines, it has been possible to moni-tor more than one of the same

class, or those with a similar indication, although not always concur-rently

(Table 25.2). Having comparators has obvi-ous advantages, but unlike a clinical

trial, there are often confounders that can make interpretation of differences

difficult (Beggs et al., 1999).

Concurrent monitoring is valuable as it reduces the likelihood of potential

confounding factors affecting the analyses and interpretation of results.

Monitoring rofecoxib and celecoxib during the same time allowed a comparison of the inci-dence of thrombotic cardiovascular events with each medicine (Harrison-Woolrych et al., 2005). The IMMP is currently monitoring four atypical antipsy-chotic medicines, which will allow useful compar-isons to be made across this class of drugs. However, for some medicines, it is not always possible to provide a suitable comparator and it may not always be desirable from the point of view of cost and the demands made of practitioners.

Related Topics