Respiratory Tract Infections

| Home | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology |Chapter: Pharmaceutical Microbiology : Clinical Uses Of Antimicrobial Drugs

Infections of the respiratory tract are among the commonest of infections, and account for much consultation in general practice and a high percentage of acute hospital admissions. They are divided into infections of the upper respiratory tract, involving the ears, throat, nasal sinuses and the trachea, and the lower respiratory tract (LRT), where they affect the airways, lungs and pleura.

RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS

Infections of the respiratory tract are among the commonest of infections,

and account for much consultation in general practice and a high percentage of

acute hospital admissions. They are divided into infections of the upper

respiratory tract, involving the ears, throat, nasal sinuses and the trachea,

and the lower respiratory tract (LRT), where they affect the airways, lungs and

pleura.

a)

Upper Respiratory

Tract Infections

Acute pharyngitis presents a diagnostic

and therapeutic dilemma. The majority of sore throats are caused by a variety

of viruses; fewer than 20% are bacterial and hence potentially responsive to

antibiotic therapy. However, antibiotics are widely prescribed and this

reflects the difficulty in discriminating streptococcal from non-streptococcal

infections clinically in the absence of microbiological documentation.

Nonetheless, Strep. pyogenes is the most

important bacterial pathogen and this responds to oral penicillin. However, up

to 10 days’ treatment is required for its eradication from the throat. This

requirement causes problems with compliance as symptomatic improvement generally

occurs within 2–3 days.

Although viral infections are important causes of both otitis media and

sinusitis, they are generally self limiting. Bacterial infections may

complicate viral illnesses, and are also primary causes of ear and sinus

infections. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae are the

commonest bacterial pathogens. Amoxicillin is widely prescribed for these

infections as it is microbiologically active, penetrates the middle ear and

sinuses, is well tolerated and has proved effective.

b)

Lower Respiratory

Tract Infections

Infections of the LRT include pneumonia, lung abscess, bronchitis,

bronchiectasis and infective complications of cystic fibrosis. Each presents a

specific diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, which reflects the variety of

pathogens involved and the frequent difficulties in establishing an accurate

microbial diagnosis. The laboratory diagnosis of LRT infections is largely

dependent upon culturing sputum. Unfortunately this may be contaminated with

the normal bacterial flora of the upper respiratory tract during expectoration.

In hospitalized patients, the empirical use of antibiotics before admission

substantially diminishes the value of sputum culture and may result in

overgrowth by non-pathogenic microbes, thus causing difficulty with the

interpretation of sputum culture results. Alternative diagnostic samples

include needle aspiration of sputum directly from the trachea or of fluid

within the pleural cavity. Blood may also be cultured and serum examined for

antibody responses or microbial antigens. In the community, few patients will

have their LRT infection diagnosed microbiologically and the choice of

antibiotic is based on clinical diagnosis.

i)

Pneumonia

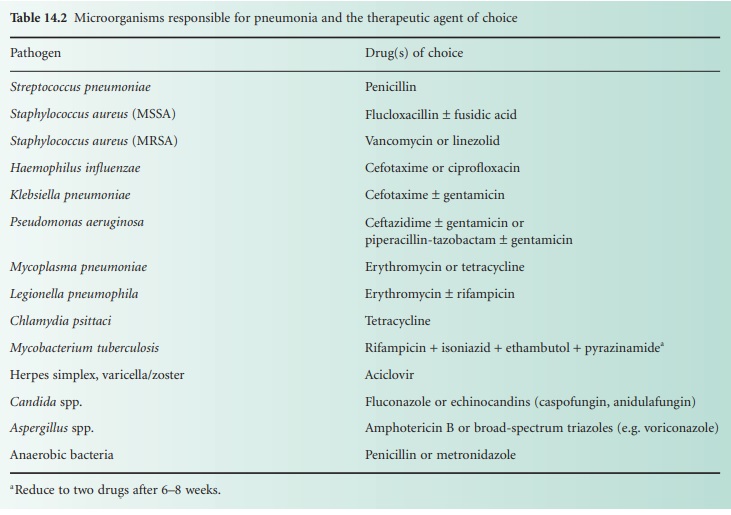

The range of pathogens causing acute

pneumonia includes viruses, bacteria and, in the immuno-compromised host,

parasites and fungi. Table 14.2 summarizes

these pathogens and indicates drugs appropriate for their treatment. Clinical

assessment includes details of the evolution of the infection, any evidence of

a recent viral infection, the age of the patient and risk factors such as

corticosteroid therapy or pre-existing lung disease. The extent of the pneumonia,

as assessed clinically or by X ray, is also important.

Streptococcus pneumoniae remains the commonest cause of pneumonia and still responds well

to penicillin despite a global increase in isolates showing reduced susceptibility

to this agent. So called ‘respiratory quinolones’ such as levofloxacin and

moxifloxacin, which exhibit increased activity against Gram positive organisms

compared to ciprofloxacin, are an alternative. A number of atypical infections

may cause pneumonia and include Mycoplasma pneumoniae,

Legionella pneumophila, psittacosis and occasionally Q fever.

With psittacosis there may be a history of contact with parrots or budgerigars;

while legionnaires’ disease has often been acquired during hotel holidays in

the Mediterranean area. The atypical pneumonias, unlike pneumococcal pneumonia,

do not respond to penicillin. Legionnaires’ disease is treated with

erythromycin and, in the presence of severe pneumonia, rifampicin is added to

the regimen. Mycoplasma infections are best treated with either erythromycin or

tetracycline, while the latter drug is indicated for both psittacosis and Q

fever.

ii)

Lung abscess

Destruction of lung tissue may lead to

abscess formation and is a feature of aerobic Gram-negative bacillary and Staph. aureus infections. In addition, aspiration

of oropharyngeal secretion can lead to chronic low grade sepsis with abscess

formation and the expectoration of foul smelling sputum that characterizes

anaerobic sepsis. The latter condition responds to high dose penicillin, which

is active against most of the normal oropharyngeal flora, while metronidazole

may be appropriate for strictly anaerobic infections. In the case of aerobic

Gram-negative bacillary sepsis, aminoglycosides, with or without a

broad-spectrum cephalosporin, are the agents of choice. Acute staphylococcal

pneumonia is an extremely serious infection and requires treatment with high

dose flucloxacillin alone or in combination with fusidic acid.

iii)

Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis is a multisystem

congenital abnormality that often affects the lungs and results in recurrent

infections, initially with Staph. aureus, subsequently with H. influenzae and

eventually leads on to recurrent Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection.

The last organism is associated with copious quantities of purulent sputum that

are extremely difficult to expectorate. Ps. aeruginosa is a co factor in the

progressive lung damage that is eventually fatal in these patients. Repeated

courses of antibiotics are prescribed and although they have improved the

quality and longevity of life, infections caused by Ps. aeruginosa are

difficult to treat and require repeated hospitalization and administration of

parenteral antibiotics such as an aminoglycoside, either alone or in

combination with an antipseudomonal penicillin or cephalosporin. The dose of

aminoglycosides tolerated by these patients is often higher than in normal

individuals and is associated with larger volumes of distribution for these and

other agents. Some benefit may also be obtained from inhaled aerosolized antibiotics.

Unfortunately drug resistance may emerge and makes drug selection more

dependent upon laboratory guidance.

Related Topics