Treatment of Tuberculosis

| Home | | Pharmacology |Chapter: Essential pharmacology : Antitubercular Drugs

The conventional 12–18 month treatment has been replaced by more effective and less toxic 6 month treatment which also yields higher completion rates.

TREATMENT OF TUBERCULOSIS

The therapy of tuberculosis has undergone remarkable change.

The conventional 12–18 month treatment has been replaced by more

effective and less toxic 6 month treatment which also yields higher completion

rates. This has been possible due to better understanding of the biology of

tubercular infection and the differential properties of the antitubercular

drugs.

Biology Of Tubercular Infection

M. tuberculosis is an aerobic organism. In

unfavourable conditions it grows only intermittently or remains dormant for

prolonged periods. Several subpopulations of bacilli, each with a distinctive

metabolic state, could exist in an infected patient, e.g.:

a) Rapidly growing with high

bacillary load as in the wall of a cavitary lesion where oxygen tension is

high and pH is neutral. These bacilli are highly susceptible to H and to a lesser

extent to R, E and S.

b)

Slow growing located

intracellularly (in macrophages) and at inflamed sites

where pH is low. They are particularly vulnerable to Z, while H, R and E are

less active, and S is inactive.

c)

Spurters within caseous

material where oxygen tension is low but pH

is neutral: the bacilli grow intermittently with occasional spurts of active

metabolism. R is most active on this subpopulation.

d)

Dormant some bacilli remain

totally inactive for prolonged periods. No

antitubercular drug is significantly active against them.

However, there is

continuous shifting of bacilli between these subpopulations.

The goals of

antitubercular chemotherapy are:

Kill Dividing

Bacilli: Drugs with early

bactericidal action rapidly reduce bacillary load in the patient and achieve quick

sputum negativity so that the patient is noncontagious to the community:

transmission of TB is interrupted. This also affords quick symptom relief.

Kill Persisting

Bacilli: To effect cure and prevent

relapse. This depends on sterilizing capacity of the drug.

Prevent Emergence Of Resistance: So that the bacilli remain

susceptible to the drugs.

The relative activity

of the first line drugs in achieving these goals differs, e.g. H and R are the most

potent bactericidal drugs active against all populations of TB bacilli, while Z

acts best on intracellular bacilli and those at inflamed sites— has very good

sterilizing activity. On the other hand S is active only against rapidly

multiplying extracellular bacilli. E is bacteriostatic—mainly serves to prevent

resistance and may hasten sputum conversion.

Drug combinations are

selected to maximise the above actions together with considerations of cost,

convenience and feasibility. The general principles of antitubercular

chemotherapy are:

· Use of any single drug in tuberculosis results

in the emergence of resistant organisms and relapse in almost 3/4th patients. A

combination of two or more drugs must be used. The rationale is: the incidence

of resistant bacilli to most drugs ranges from 10–8 to 10–6. Because an average

patient of pulmonary tuberculosis harbours 108 to 1010 bacilli, the number of

organisms that will not respond to a single drug is high and cannot be dealt by

the host defence. During protracted treatment, these bacilli multiply and

become dominant in 3–4 months. Because insensitivity to one drug is independent

of that to another, i.e. incidence of H resistance among bacilli resistant to R

will be 10–6 and vice versa; only few

bacilli will be resistant to both; these can be handled by host defence. By the

same rationality, massive infection (>1010 organisms) has to be treated by

at least 3 drugs; and a single drug is sufficient for prophylaxis, because the number

of bacilli is small.

· Isoniazid and R are

the most efficacious drugs; their combination is definitely synergistic—

duration of therapy is shortened from > 12 months to 9 months. Addition of Z

for the initial 2 months further reduces duration of treatment to 6 months.

· A single daily dose of

all first line antitubercular drugs is preferred. The ‘directly observed

treatment short course’ (DOTS) was recommended by the WHO in 1995.

· Response is fast in

the first few weeks as the fast dividing bacilli are eliminated rapidly.

Symptomatic relief is evident within 2–4 weeks. The rate of bacteriological,

radiological and clinical improvement declines subsequently as the slow

multiplying organisms respond gradually. Bacteriological cure takes much

longer. The adequacy of any regimen is decided by observing sputum conversion

rates and 2–5 year relapse rates after completion of treatment.

Conventional Regimens

These consist of H + Tzn or E with or without S (for

initial 2 months) and require 12–18 months therapy. Failure rates are high,

compliance is poor—therefore not recommended now.

SHORT COURSE CHEMOTHERAPY (SCC)

These are regimens of

6–9 month duration which have been found highly efficacious. After several

years of experience a WHO expert group has framed clearcut treatment guidelines*

(1997) for different categories of TB patients. The dose of first line antiTB

drugs has been standardized on body weight basis and is applicable to both

adults and children (Table 55.1).

All regimens have an initial intensive phase, lasting for 2–3

months aimed to rapidly kill the TB bacilli, bring about sputum conversion and

afford symptomatic relief. This is followed by a continuation phase lasting for 4–6 months during which the remaining bacilli are

eliminated so that relapse does not occur. Treatment of TB is categorized by:

· Site of disease (pulmonary or extrapulmonary)

and its severity: the bacillary load and acute threat to life or permanent

handicap are taken into consideration.

· Sputum smear positivity/negativity: positive

cases are infectious and have higher mortality.

· History of previous treatment: risk of drug

resistance is more in irregularly treated patients.

Rationale Patients of smear-positive

pulmonary TB harbour and

disseminate large number of![]() bacilli. Initial treatment with 4 drugs

reduces risk of selecting resistant bacilli as well as covers patients with

primary resistance. When few bacilli are left only 2 drugs in the continuation

phase are enough to effect cure. Smear-negative pulmonary TB and extrapulmonary

TB patients harbour fewer bacilli in their lesions—risk of selecting resistant

bacilli is less; regimens containing only 3 drugs in the initial phase and 2 in

the continuation phase are of proven efficacy. Accordingly, previously

treated/failure/default/ relapse cases are treated with a longer intensive

phase—5 drugs for 2 months and 4 drugs for 1 month followed by 3 drugs in the

continuation phase of 5 months duration (instead of usual 4 months).

bacilli. Initial treatment with 4 drugs

reduces risk of selecting resistant bacilli as well as covers patients with

primary resistance. When few bacilli are left only 2 drugs in the continuation

phase are enough to effect cure. Smear-negative pulmonary TB and extrapulmonary

TB patients harbour fewer bacilli in their lesions—risk of selecting resistant

bacilli is less; regimens containing only 3 drugs in the initial phase and 2 in

the continuation phase are of proven efficacy. Accordingly, previously

treated/failure/default/ relapse cases are treated with a longer intensive

phase—5 drugs for 2 months and 4 drugs for 1 month followed by 3 drugs in the

continuation phase of 5 months duration (instead of usual 4 months).

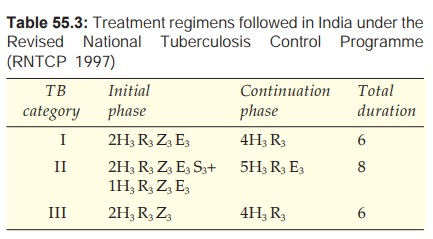

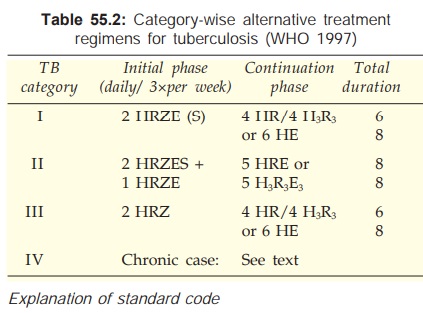

The categorywise treatment regimens are summarized in Tables 55.2 and 55.3.

Category I

This category

includes:

·

New (untreated) smear-positive pulmonary TB.

·

New smear-negative pulmonary TB with extensive

parenchymal involvement.

·

New cases of severe forms of extrapulmonary

TB, viz. meningitis, miliary,

pericarditis, peritonitis, bilateral or extensive pleural effusion, spinal,

intestinal, genitourinary TB.

Initial Phase

Four drugs HRZ + E or

S are given daily or thrice weekly

for 2 months. The revised national tuberculosis control programme (RNTCP) has

been launched in India in 1997, which is implementing DOTS*. Out of the WHO

recommended regimens, the RNTCP has decided to follow thrice weekly regimen,

since it is equally effective, saves drugs and effort, and is more practical.

The RNTCP regimen is presented in Table 55.3. The RNTCP recommends that if the

patient is still sputumpositive at 2 months, the intensive phase should be

extended by another month; then continuation phase is started regardless of

sputum status at 3 months.

· Each antiTB drug has a standard

abbreviation (H, R, Z, E, S).

· The numeral before a phase is the

duration of that phase in months.

· The numeral in subscript (e.g. H3

R3) is number of doses of that drug per week. If there is no

subscript numeral, then the drug is given daily.

Continuation

Phase

Two drugs HR for 4 months or HE for 6 months are given. When both H and

R are used, thrice weekly regimen is permissible. Under the RNTCP, thrice

weekly treatment with H and R is given for 4 months. This phase is extended to

6–7 months (total duration 8–9 months) for TB meningitis, miliary and spinal

disease. In areas where DOTS has not been implemented, use of Tzn in place of E

in the continuation phase is permitted except in HIV positive cases.

Category

II

These are smear-positive

failure, relapse and

interrupted treatment cases:

Treatment failure: Patient who remains or again becomes smear-positive 5 months or

later after commencing treatment. Also one who was smear-negative at start of

therapy and becomes smear-positive after the 2nd month.

Relapse:

A patient declared cured from any form of TB in the past after receiving one full course of chemotherapy

and now has become sputum positive.

Treatment After Interruption (Default): A patient who interrupts treatment for 2 months or more and returns with sputum-positive

or clinically active TB.

These patients may have resistant bacilli and are at greater

risk of developing MDRTB.

Initial phase

All 5 first line drugs

are given for 2 months followed by 4

drugs (HRZE) for another month. Continuation phase is started if sputum is negative,

but 4 drug treatment is continued for another month if sputum is positive at 3

months.

Continuation phase

Three drugs (HRE) are given for 5 months either

daily or thrice weekly (only thrice weekly under the RNTCP).

Category III

These are new cases of smear-negative pulmonary TB with limited

parenchymal involvement or less severe forms of extrapulmonary TB, viz, lymph node TB, unilateral pleural

effusion, bone (excluding spine), peripheral joint or skin TB.

Initial Phase

Three drugs (HRE) given for 2 months are enough because

the bacillary load is smaller.

Continuation Phase

This is similar to

category I, i.e. 4 month

daily/thrice weekly HR or 6 months daily HE (Tzn) therapy. Under the RNTCP only

thrice weekly HR regimen is followed.

Category IV

These are chronic cases who have remained or have

become smear-positive after completing fully supervised retreatment (Category

II) regimen. These are most likely MDR cases.

Multi-Drug-Resistant (MDR) TB is defined as resistance to both H and R and may be any number

of other anti-TB drugs. MDRTB has a more rapid course (some die in 4–16 weeks).

Treatment of these cases is difficult, because one or more second line drugs

are to be given for 12–24 months. The second line drugs are less efficacious,

less convenient, more toxic and more expensive.

The choice of drugs

depends on the drugs used in the earlier regimen, dosage and regularity with

which they were taken, presence of associated disease like AIDS/diabetes/leukaemia/silicosis,

and whether sensitivity of the pathogen to various drugs is known (by in vitro testing) or unknown. If

sensitivity of the TB bacilli is known, the drug/ drugs to which they are

resistant is/are excluded and other first line drugs are prescribed along with

1–3 second line drugs. A total of 5–6 drugs are given. One of the FQs is

generally included. In case streptomycin is not being given, one out of

kanamycin/amikacin/capreomycin should be added, because they are

tuberculocidal.

a)

For H resistance—RZE given for 12 months is

recommended.

b)

For H + R resistance—ZE + S/Kmc/Am/Cpr +

Cipro/ofl ± Etm could be used.

The actual regimen is

devised according to the features of the individual patient.

Extensively Drug Resistant (XDR) TB

Recently, the WHO and CDC (USA) have identified TB cases

that are ‘extensively drug resistant’. This term has been applied to bacilli

that are resistant to at least 4 most effective cidal drugs, i.e. cases

resistant to H, R, a FQ, one of Kmc/Am/Cpr with or without any number of other

drugs. The global survey for the period 20022004 has found 20% TB isolates to

be MDR, out of which 2% were XDR. The XDRTB is virtually untreatable; mortality

is high, particularly among HIV positive patients.

Tuberculosis In Pregnant Women

The WHO and British Thoracic

Society consider H, R and Z to be safe to the foetus and recommend the standard

6 month (2HRZ + 4HR) regimen for pregnant women with TB. E can be added during

late but not early pregnancy. S is contraindicated. However, Z is not

recommended in the USA (due to lack of adequate teratogenicity data). In India,

it is advised to avoid Z, and to treat pregnant TB patients with 2 HRE + 7HR

(total 9 months). Treatment of TB should not be withheld or delayed because of

pregnancy.

Treatment Of Breastfeeding Women

All antiTB drugs are

compatible with breastfeeding; full course should be given to the mother, but

the baby should be watched (See

Appendix3). The infant should receive BCG vaccination and isoniazid

prophylaxis.

Management Of Patients With

Adverse Drug Reactions To Antitubercular Drugs

Minor side effects are to be

managed symptomatically without altering medication; e.g. Z induced arthralgia

can be treated by analgesicNSAIDs; peripheral neuritis due to H can be counteracted

by pyridoxine. With more severe reactions, the offending drug should be stopped;

e.g. E should be promptly discontinued at the first indication of optic

neuritis. If possible H and R should be continued, or should be reintroduced

after the reaction has subsided by challenging with small doses. However, R

should never be reintroduced in case of severe reaction such as haemolysis,

thrombocytopenia or renal failure.

Hepatotoxicity is the most common problem with antitubercular

drugs. Any one or more of H, R and Z could be causative and the reaction occurs

more frequently when combination of these drugs is used. In case hepatitis

develops, all these drugs should be stopped and S + E may be started or

continued. A fluoroquinolone may be added. When the reaction clears, the above

drugs are started one by one to identify the culprit, which should never be

used again, while the others found safe should be continued. It is best to

avoid Z in patients who once developed hepatitis.

Chemoprophylaxis

The purpose is to prevent progression of latent

tubercular infection to active disease. This is indicated only in :

a)

Contacts of open cases who show recent Mantoux

conversion.

b)

Children with positive Mantoux and a TB

patient in the family.

c)

Neonate of tubercular mother.

d)

Patients of leukaemia, diabetes, silicosis, or

those who are HIV positive but are not anergic, or are on corticosteroid

therapy who show a positive Mantoux.

e) Patients with old inactive disease who are

assessed to have received inadequate therapy.

The standard drug for

chemoprophylaxis of TB is H 300 mg (10 mg/kg in children) daily for 6–12

months. This is as effective in HIV patients as in those with normal immune

function. However, because of spread of INH resistance, a combination of H (5

mg/kg) and R (10 mg/kg) daily given for 6 months is preferred in some areas.

The CDC (USA) recommends 4 months R prophylaxis in case H cannot be used. An

alternative regimen is daily R + Z for 2 months, but this carrys risk of severe

liver damage, and needs close monitoring. Therefore, it is reserved for

contacts of resistant TB cases. Another regimen for subjects exposed to MDRTB

is E + Z with or without a FQ.

Role of corticosteroids

Corticosteroids should not be ordinarily used in tubercular patients.

However, they may be used under adequate chemotherapeutic cover:

a) In seriously ill patients (miliary or severe

pulmonary TB) to buy time for drugs to act.

b) When hypersensitivity reactions occur to

antitubercular drugs.

c) In meningeal or renal TB or pleural effusion—

to reduce exudation and prevent its organisation, strictures, etc.

d) In AIDS patients with severe manifestations of

tuberculosis.

Corticosteroids are contraindicated

in intestinal tuberculosis—silent perforation can occur. Corticosteroids, if

given, should be gradually withdrawn when the general condition of the patient

improves.

Tuberculosis In AIDS Patients

The association of HIV and TB infection is a serious problem.

HIV positive cases have more severe and more infectious TB. HIV infection is

the strongest risk factor for making latent TB overt. Moreover, adverse

reactions to antiTB drugs are more common in HIV patients.

On the other hand, institution of ‘highly active antiretroviral

therapy’ (HAART) and improvement in CD4 cell count markedly reduces the incidence

of TB among HIVAIDS patients. When CD4 count is <150 cells/μL, extrapulmonary and

dual TB is more commonly encountered.

In case of M. tuberculosis infection, drugs used

are the same as in non-HIV cases, but the duration is longer and at least 4

drugs are used. Initial therapy with 2 month HRZE is started immediately on the

diagnosis of TB, and is followed by a continuation phase of HR for 7 months

(total 9 months). Alternatively, 3 drugs (HRE) are given for 4 months in the

continuation phase. Pyridoxine 25–50 mg/day is routinely given along with H to

counteract its neurological side effects, which are more likely in AIDS patients.

Consideration also has

to be given to possible drug interactions between anti-TB and antiretroviral

(ARV) drugs. Rifampin, a potent inducer of CYP isoenzymes, markedly enhances

the metabolism of protease inhibitors (PIs, viz.

indinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir) and of NNRTIs, viz. nevirapine, efavirenz, to a lesser extent, making them ineffective. In patients receiving

these drugs, rifabutin (a less potent enzyme inducer) given for 9–12 months may

be substituted for rifampin. The metabolism of nucleoside reverse transcriptase

inhibitors (NRTIs, zidovudine, etc.) is not induced by rifampin—no dose

adjustment is needed. An alternative regimen of 3 NRTIs (zidovudine +lamivudine

+ abacavir) has been advocated for patients who are to be treated by rifampin.

MDRTB in HIVAIDS

patients should be treated for a total of 18–24 months or for 12 months after

sputum smear negativity.

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection is common in HIVAIDS

patients, particularly when the CD4 count drops to < 100 cells/μL.

Clarithromycin/azithromycin are the most active drugs against MAC. A favoured

regimen consists of an intensive phase of at least 4 drugs—

clarithromycin/azithromycin + ethambutol + rifabutin + one FQ/clofazimine/ethionamide

given for 2–6 months (duration is response based), followed by 2 drug

maintenance phase with clarithromycin/azithromycin + ethambutol/one

FQ/rifabutin for at least 12 months or even lifelong. However, any additional

benefit of the initial 4 drug intensive phase is unproven. Clarithromycin

inhibits the metabolism of rifabutin.

Prophylaxis of MAC in

AIDS patients by clarithromycin/azithromycin (or rifabutin if these drugs

cannot be given) is advocated when the CD4 count falls below 100 cells/μL. After institution

of HAART, this is continued till near complete suppression of viral replication

is achieved and CD4 count rises above 100 cells/ μL. Otherwise,

prophylaxis is continued lifelong.

Related Topics