Antitubercular Antibiotics

| Home | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology | | Pharmaceutical Microbiology |Chapter: Pharmaceutical Microbiology : Antibiotics And Synthetic Antimicrobial Agents: Their Properties And Uses

The antibiotics used for the treatment of tuberculosis belong to a variety of chemical classes, but it is convenient to consider them together in the same section..

ANTITUBERCULAR ANTIBIOTICS

The antibiotics used for the treatment of tuberculosis

belong to a variety

of chemical classes,

but it is convenient to consider them

together in the same section

for two reasons: first, most

of them are used exclusively for tuberculosis, and

second, therapy extends

over several months, during which time resistance development is a significant

possibility. This risk is minimized by the use of two or

three antibiotics in combination, so it is appropriate to consider them together because that

represents their normal

pattern of use.

Streptomycin, introduced in the late 1940s,

was the

first effective treatment for tuberculosis, but

its use in isolation was short lived

because of the ease with which the bacteria

became resistant to a single antibiotic.

Isoniazid, which became

available about 5 years later, was used first in combination with streptomycin then with

rifampicin after the latter was introduced in 1967. The combination of isoniazid and rifampicin has

been the mainstay of tuberculosis therapy

from that time until the present

day, although other drugs like pyrizinamide and ethambutol have been added

to the combination, and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis has become an increasing problem in recent years;

this is, by definition,

simultaneous resistance to isoniazid and rifampicin.

Tuberculosis

may be caused by any

one of three Mycobacterium

species, but all three

characteristically grow slowly in the body and may persist for long periods in a near dormant

state. Because the course of therapy is normally 4–6 months,

antibiotics that are orally effective are much preferred; this is because

unsupervised patients are more likely

to take oral

medicines, and in many countries

where patients may have difficulty travelling to clinics the daily

administration of injectable antibiotics

is not feasible. The ideal antitubercular drug should also have

the potential to kill rather

than merely inhibit the

growth of the infecting organism. Because mycobacteria can survive, and even reproduce, within macrophages, relying on the immune system to eradicate

an infection

following the use of a bacteristatic drug is

unlikely to be an effective strategy.

Rifampicin kills dormant bacteria, while pyrizinamide is active against bacteria that are slowly

reproducing in acidic

environments; isoniazid is most useful against more rapidly growing cells.

The current approach is

to treat tuberculosis in two phases:

an initial phase of 2 months using isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrizinamide (with

or without ethambutol), and a

4 month continuation phase with isoniazid and rifampicin. If, however,

the infecting organism

is resistant to any of the above,

second-line drugs may be

used and the duration of treatment possibly

extended. The status

of streptomycin is equivocal; it is now rarely

used in the UK and is not a first-choice treatment recommendation of the European

Respiratory Society either,

but it is more commonly

used in front-line therapy in the USA. Second-line drugs

available for infections caused by resistant organisms, or when first-line drugs cause unacceptable side effects, include amikacin, capreomycin, cycloserine, newer macrolides

(e.g. azithromycin and clarithromycin) and moxifloxacin. Drug regimens are

often indicated using a shorthand notation with single letters to indicate the drugs employed, initial numbers indicating

months of therapy and following numbers (which

may be in parentheses or subscripts) indicating days per week. For example, 2RHZ(E)/4HR(3) or 2RHZ(E)/4HR3 would mean 2 months of rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrizinamide (with the possible

addition of ethambutol) followed by 4 months of isoniazid and rifampicin three times

per week. Several

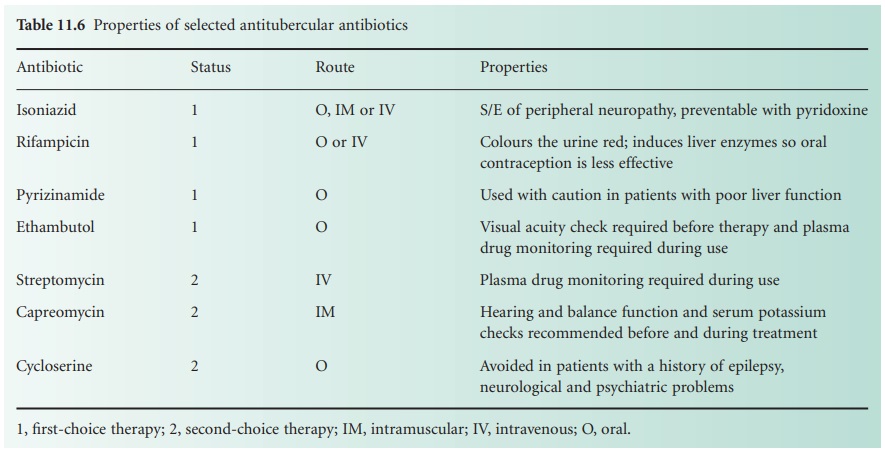

of the antitubercular drugs have specific contraindications or require monitoring during

use; some of these requirements and cautions are shown in Table 11.6.

Rifampicin is the only

one of the common antitubercular drugs that is used in the treatment of

non-mycobacterial infections. It is active

against Gram-positive bacteria and some Gram-negative species, but not

Enterobacteriaceae or

pseudomonads. Rifampicin possesses significant bactericidal activity at very low concentrations against staphylococci.

Unfortunately, resistant mutants may arise

very rapidly, both

in vitro and in vivo, so it has been recommended that rifampicin should be

combined with another antibiotic, e.g. vancomycin, in the

treatment of staphylococcal infections. Rifabutin, a semisynthetic

rifamycin, may be used in the prophylaxis of M.

avium complex infections in immuno-compromised patients and in the treatment, with other drugs,

of pulmonary

tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections.

Related Topics