Bonding Schemes

| Home | | Organic Chemistry |Chapter: Organic Chemistry : Functional Groups and Chemical Bonding

Bond formation between atoms occurs primarily to enable each atom to achieve an inert gas electron configuration in the valence level (a valence octet for all elements except hydrogen which requires only two electrons to achieve the electronic configuration of helium).

BONDING SCHEMES

Bond

formation between atoms occurs primarily to enable each atom to achieve an

inert gas electron configuration in the valence level (a valence octet for all

elements except hydrogen which requires only two electrons to achieve the

electronic configuration of helium). An atom can achieve an inert-gas

electronic configuration by giving up electrons, accepting electrons, or

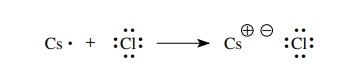

sharing electrons with another atom. An ionic bond is formed when one atom

gives up one or more electrons to reach an octet electronic configuration (as a

positively charged ion) and a second atom accepts one or more electrons to

reach an octet electronic configuration (as a negatively charged ion). For

example, the reaction of a cesium atom with a fluorine atom occurs by the

transfer of an electron from the cesium atom to the chlorine atom. By doing so,

both cesium and chlorine have reached a valence octet electron configuration.

The cesium atom has been converted to a positively charged cesium ion with the

octet electronic configuration of xenon, and the chlorine has been converted to

a negatively charged chloride ion with the octet electronic configuration of

argon. The “bond” between cesium and chlorine is due to the electrostatic

attraction of the cesium and chloride ions.

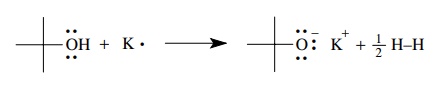

The

reaction of potassium metal with tert-butanol

gives an ionic bond between the tert-butoxy

anion and a potassium cation by transfer of electrons from potas-sium to the

hydroxyl functional group. Hydrogen is evolved as a by-product. By losing an

electron, potassium gains the octet electronic configuration of argon, oxygen

has an octet structure (three lone pairs and one pair of shared electrons), and

hydrogen has the electronic configuration of helium. (Based on functional group

behavior, any other alcohol is predicted to react with potassium in the same

way — and they do!)

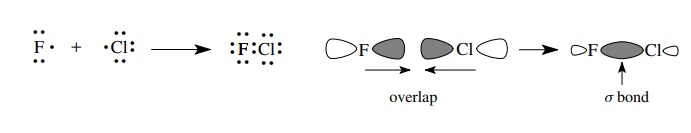

Most

bonds in organic molecules, however, are covalent bonds in which elec-trons are

shared between two atoms. Sharing electrons is a way to enable each atom of the

bonded pair to reach an octet electronic configuration without having to give

up or gain an electron. Covalent bonds are formed by the overlap of singly

occupied AOs to form new MOs that contain a pair of electrons. Each atom in

essence gains an electron by sharing. The reaction of a chlorine atom with a

fluorine atom occurs by the overlap of a singly occupied 3p orbital of chlorine

with a singly occupied 2p orbital of fluorine to give a bond between the two

atoms that contains two electrons. This is shown both by using Lewis structures

and by using orbital pictures. The type of bond formed is called a σ bond because the region of greatest

electron density falls on the internuclear axis.

This

simple picture is adequate for many diatomic molecules with univa-lent atoms,

but it is not sufficient to describe the bonding in most polyatomic molecules.

In addition to electron sharing to reach octet electronic configura-tions,

other considerations such as the number of bonds to an atom, the number of

electron pairs that are shared between two bonded atoms, and repulsion

ener-gies that are present between electron pairs require some modification of

the picture. These factors can be rationalized by the idea that valence shell

atomic orbitals (2s and 2p’s) can combine to form hybrid AOs. These hybrid AOs

over-lap with AOs of other atoms in the usual fashion to form covalent bonds.

Hybrid AOs have energies, shapes, and geometries which are intermediate between

the atomic orbitals from which they are formed. Hybridization of AOs is an

out-growth of bond formation that enables atoms to derive the greatest amount

of bond energy from electron sharing and to allow bonded atoms to achieve octet

electronic configurations.

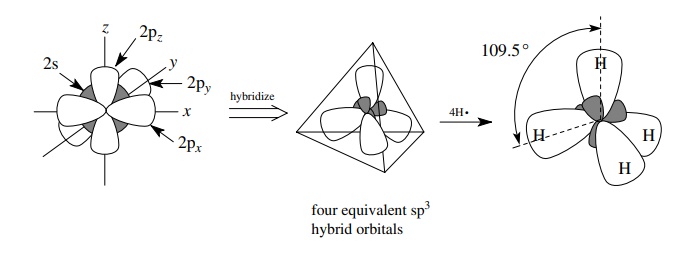

If

four single bonds and/or electron pairs originate from a single atom, then the

s orbital and the three p orbitals of the valence shell combine to form four

equivalent sp3 hybrid orbitals that are then used in bond formation

to other atoms. Depending on the number of electrons in the valence shell of

the atom, these sp3 hybrid orbitals can contain either a single

unpaired electron which can be shared with another atom by overlap and bond

formation or an unshared pair of electrons which is normally not involved in

bond formation. Thus alkanes, which have all single bonds, have carbon atoms

which are sp3 hybridized. For example, methane has four single C–H

bonds originating at carbon, and these bonds are σ bonds produced by the overlap of four sp3 hybrid

orbitals of carbon with four 1s AOs of four hydrogens to give four sp3

– 1s σ bonds from carbon to hydrogen.

The geometry of the four equivalent sp3 hybrid orbitals (and hence

the compound produced by overlap with these orbitals) is tetrahedral. Thus

methane has four equivalent C–H σ

bonds which point toward the corners of a regular tetrahedron and have H–C–H

bond angles of 109.5◦

:

In

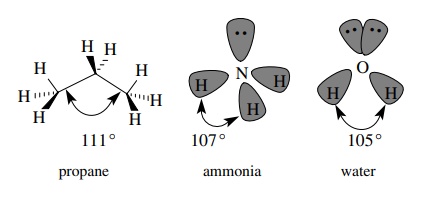

a similar fashion each carbon of propane is sp3 hybridized and

tetrahedral since each carbon has four single bonds to other atoms originating

from it. For example, the central carbon of propane has two equivalent sp3

– 1s C–H σ bonds and two equivalent

sp3 – sp3 C–C σ

bonds. (Note that sp3 orbitals from one carbon can overlap with sp3

orbitals from another carbon to produce carbon – carbon bonds.) The geometry is

very close to tetrahedral, but the C–C–C bond angle is slightly larger (111◦ ) to accommodate

the bigger CH3 groups.

Other

first-row elements can also be sp3 hybridized. The only requirement

is that they have a combination of four single bonds and/or electron pairs

originating from a single element. Ammonia, which has three N–H bonds and a

lone pair on nitrogen, is thus sp3 hybridized and has three

equivalent sp3 – 1s N–H σ

bonds and a lone pair which occupies an sp3 hybrid orbital. The

geometry is close to tetrahedral with an H–N–H bond angle of 107◦ . Other amines also

have sp3-hybridized nitrogen and are close to a tetrahedral geometry

around the nitrogen atom.

The

oxygen atom in the water molecule has two bonds and two lone pairs so it too is

sp3 hybridized. There are two equivalent sp3 – 1s O–H σ bonds and two lone pairs occupying sp3-hybridized

orbitals. Electron – electron repulsions of the lone pairs cause greater

distortions from a true tetrahedral geometry so that the H–O–H bond angle is

105◦ . Other singly

bonded oxygen functional groups such as alcohols, ethers, and acetals have sp3-hybridized

oxygens and nearly tetrahedral geometries.

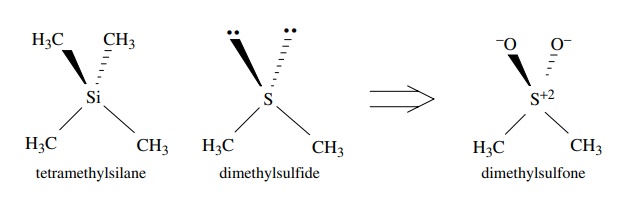

Second-row

elements such as silicon, phosphorus, and sulfur can also have sp3

hybridization of the valence shell orbitals, although hybridization is not

necessar-ily required for second-row elements. When second-row elements do

hybridize, however, the 3s and 3p AOs combine to form the sp3 hybrid

orbitals. Tetra-methylsilane, the standard reference for nuclear magnetic

resonance (NMR) spec-tra, has tetrahedral geometry and thus sp3

hybridization of the 3s and 3p valence shell orbitals of silicon. Dimethyl

sulfone has nearly tetrahedral bond angles, indi-cating that the sulfur is sp3

hybridized. Although formal charges are present, the two bonds to oxygen can be

thought to arise by the overlap of a filled sp3 orbital on sulfur

with an unfilled sp3 orbital on oxygen. The resulting σ bond is called a coordinate covalent,

or dative, bond because both of the shared electrons in the bond come from only

one of the bonded elements. Hydrogen sulfide has an H–S–H bond angle of 92◦ , which indicates

that sulfur is not hybridized in this compound.

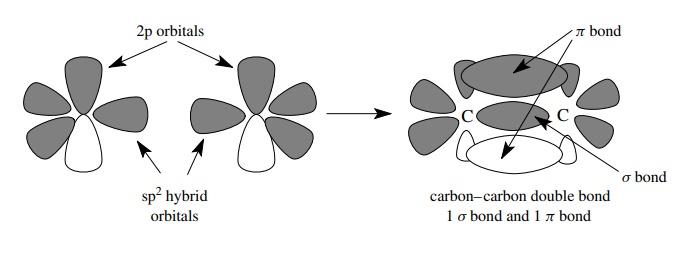

When two pairs of electrons are shared between two elements, a different bonding arrangement is required to enable the atoms to reach valence octet elec-tron configurations. Because of the Pauli exclusion principle, only one sigma bond is possible between any two atoms because only one pair of electrons can occupy the space along the internuclear axis. The second pair of electrons that is shared by the two atoms must therefore be located in space someplace other than along the internuclear axis. The second pair of shared electrons is located in a different type of covalent bond, a π bond, which has electron density found on either side of the internuclear axis. The π bonding results from the parallel overlap (or sideways overlap) of atomic p orbitals. To accommodate the need for a singly occupied atomic p orbital available for the formation of a π bond, hybridization of the valence AOs takes place between the s orbital and two of the three p atomic orbitals. Hybridization of one s and two p AOs produces three equivalent sp2 hybrid AOs and a p orbital remains unhybridized in order to produce a π bond.

This

bonding scheme permits two pairs of electrons to be shared between two atoms so

that each pair occupies a different region of space and does not violate the

Pauli exclusion principle. Since only two p orbitals are used in the

hybridization and they are orthogonal and define a plane, the sp2-hybridized

carbon is planar with bond angles of 120◦ . The remaining p orbital, which is

left unhybridized to form the π bond,

is perpendicular to the molecular plane. Once formed, the π bond keeps the entire system rigid and planar, because rotation

of one end of the π -bonded system

relative to the other end requires that the π

bond be broken.

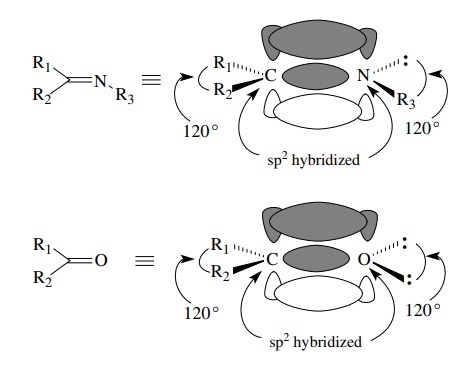

Elements

other than carbon are also sp2 hybridized if they share two electron

pairs with another atom. Thus imines have sp2-hybridized nitrogen

(and carbon) to account for formation of the C–N double bond. The lone pair on

nitrogen occupies an sp2 hybrid orbital. The bond angles are all 120◦ around both carbon

and nitrogen since both are sp2 hybridized. Similar considerations

hold for the oxygen atom of carbonyl groups of all kinds. The two unshared

pairs of electrons on oxygen both occupy sp2 orbitals. The

interorbital angle is 120◦

, as expected for trigonal hybridization.

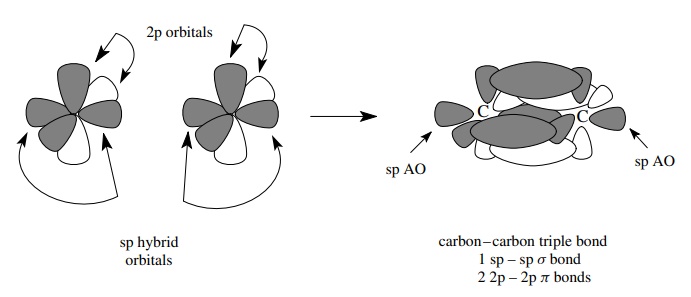

The

sharing of three pairs of electrons between two atoms can be accomplished by

extrapolation of the above considerations. That is, since there can only be one

σ bond connecting the atoms, then the other two pairs of shared electrons must

be in two different π bonds, each of

which is formed by the parallel overlap of a p orbital. Furthermore the π bonds must be mutually orthogonal so

as not to violate the Pauli exclusion principle. Hybridization of one s orbital

and one p orbital gives two equivalent sp hybrid AOs which are linearly

opposite to one another.

The

two remaining p atomic orbitals, which are mutually orthogonal, are used to

produce two orthogonal π bonds. The

geometry of triply bonded systems is thus linear about the triple bond.

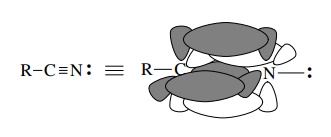

Similar

considerations apply to the triply bonded nitrogen found in nitriles. The

sp-hybridized carbon and nitrogen atoms form an sp – sp σ bond and two 2p – 2p π

bonds between carbon and nitrogen. The unshared pair on nitrogen occupies an sp

hybrid orbital.

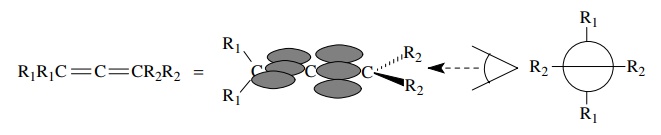

Another

instance where sp hybridization is required occurs in molecules with cumulated

double bonds such as allenes, ketenes, and carbodiimides. The end atoms of the

cumulated units are sp2 hybridized because each shares two electron

pairs with another element (the central carbon) and there is a σ and a π bond. The structure, however, requires that two π bonds originate from the central

carbon — one π bond going toward one

end of the cumulated system, the other π

bond going toward the other end. Thus two 2p AOs are required for π bonding from the central carbon and sp

hybridization is appropriate. Consequently the geometry is linear at the middle

atom and trigonal at the end atoms. A further consequence of the orthogonal π bonds is that planar bonds originating

at the end carbons lie in two orthogonal planes with a dihedral angle of 90◦ . (A dihedral angle

is the angle made by two intersecting planes.)

Besides

providing a theoretical framework by which the structure, geometry, and octet

structure of bonded elements can be explained and understood, the concept of

hybridization also predicts the ordering of stabilities and energies of bonds

and the energy of lone pairs of electrons in hybrid orbitals. Because s AOs are

of lower energy than p AOs, hybrid orbitals with a greater proportion of s

character should be more stable and thus form stronger bonds. Unshared pairs of

electrons in hybrid orbitals with greater s character should also be of lower

energy (more stable). As the percentage of s character of hybrid orbitals

increases in the order sp3 – 25% s character < sp2 – 33% s character < sp – 50% s character, it is found that the strength of bonds

formed by overlap with those orbitals increases in a parallel fashion. For

example, the bond dissociation ener-gies of primary C–H bonds have been

measured and fall in the order that is predicted by the percentage of s

character of the hybrid orbitals on carbon: sp3 C–H, 105 kcal/mol;

sp2 C–H, 111 kcal/mol; and sp C–H, 133 kcal/mol. Elec-tron pairs are

more stable in orbitals with more s character; thus the acidities of primary

C–H bonds are found to be sp3 C–H, pKa =

50; sp2 C–H, pKa

= 44; and sp C–H, pKa = 25. This is due to the fact that

the anions formed by pro-ton removal give carbanions that have the negative

charge in sp3, sp2, and sp orbitals, respectively.

Because the lone pair is more stable in an orbital of greater s character, the

anion formed by removal of an sp C–H proton is more sta-ble (and hence the

proton is more easily removed) than the anion formed by removal of an sp2

C–H proton, which in turn is more stable (and hence the proton is more easily

removed) than the anion formed by removal of an sp3 C–H proton.

Other examples of the effects of greater s character in orbitals are

encountered routinely.

The

concept of hybridization of AOs to give new hybrid AOs involved in the bonding

patterns of atoms is a useful and practical way to describe the way in which

functional groups are constructed. It provides a rationale for the structure as

well as the geometry and electron distribution in functional groups and

molecules in which they are found. It can also be used to predict reactivity

patterns of functional groups based on these considerations.