Molecules that Influence Obesity

| Home | | Biochemistry |Chapter: Biochemistry : Obesity

The cause of obesity can be summarized in a deceptively simple statement of the first law of thermodynamics: Obesity results when energy (caloric) intake exceeds energy expenditure.

MOLECULES THAT INFLUENCE OBESITY

The cause of obesity

can be summarized in a deceptively simple statement of the first law of

thermodynamics: Obesity results when energy (caloric) intake exceeds energy

expenditure. However, the mechanism underlying this imbalance involves a

complex interaction of biochemical, neurologic, environmental, and psychologic

factors. The basic neural and humoral pathways that regulate appetite, energy

expenditure, and body weight involve systems that regulate short-term food

intake (meal to meal), and signals for the long-term (day to day, week to week,

year to year) regulation of body weight (Figure 26.7).

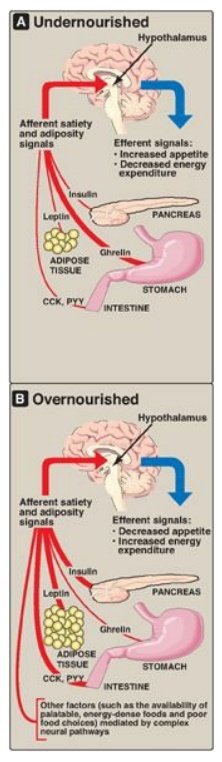

Figure 26.7 Some signals that influence appetite and satiety. CCK = cholecystokinin, PYY = peptide YY.

A. Long-term signals

Long-term signals

reflect the status of TAG stores.

1. Leptin: Leptin is an adipocyte peptide hormone that is

secreted in proportion to the size of fat stores. When we consume fewer

calories than we need, body fat declines, and leptin production from the fat

cell decreases. The body adapts by minimizing energy utilization (decreasing

activity) and increasing appetite. Unfortunately, in many individuals, the

leptin system may be better at preventing weight loss than preventing weight

gain. Although a meal or overeating increases leptin and this should, in

theory, also dampen appetite (an anorexigenic effect) and prevent

overconsumption of calories, other cues that stimulate appetite can apparently

overcome the leptin system in many individuals. [Note: Leptin’s effects are

mediated through binding to its receptors in the arcuate nucleus of the

hypothalamus.]

2. Insulin: Obese individuals are also hyperinsulinemic. Like

leptin, insulin acts on hypothalamic neurons to dampen appetite. (See Chapter

23 for the effects of insulin on metabolism.)

B. Short-term signals

Short-term signals from the gastrointestinal tract control hunger and satiety, which affect the size and number of meals over a time course of minutes to hours. In the absence of food intake (between meals), the stomach produces ghrelin, an orexigenic (appetite-stimulating) hormone that drives hunger. As food is consumed, gut hormones, including cholecystokinin (CCK) and peptide YY, among others, induce satiety (an anorexigenic effect), thereby terminating eating, through actions on gastric emptying and neural signals to the hypothalamus. Within the hypothalamus, neuropeptides such as neuropeptide Y (orexigenic) and α-melanocyte–stimulating hormone (α-MSH), which is anorexigenic, and neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and dopamine, are important in regulating hunger and satiety. Long-term and short-term signals interact, insofar as leptin can affect the sensitivity of hypothalamic neurons to short-term signals such as CCK. Thus, there are many and complex regulatory loops that control the size and number of meals in relationship to the status of body fat stores. [Note: α-MSH binds to the melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R). Loss-of-function mutations to MC4R are associated with early-onset obesity.]

Related Topics