Control of Breathing

| Home | | Anatomy and Physiology | | Anatomy and Physiology Health Education (APHE) |Chapter: Anatomy and Physiology for Health Professionals: Respiratory System

Respiratory control has both involuntary and voluntary components. The involuntary centers of the brain regulate the respiratory muscles. They control respiratory minute volume by adjusting the depth and frequency of pulmonary ventilation.

Control

of Breathing

Respiratory control has both involuntary and voluntary

components. The involuntary centers of the brain regulate the respiratory

muscles. They control respiratory minute volume by adjusting the depth and

frequency of pulmonary ventilation. This occurs in response to sensory

information that arrives from the lungs, various portions of the respiratory

tract, and a variety of other sites.

The respiratory

areas of the brain control inspi-ration as well as exhalation.

The voluntary control of respiration reflects activity in the cerebral cortex

that affects either the output of the respiratory center in the medulla

oblongata and pons or the output of motor neurons in the spinal cord that

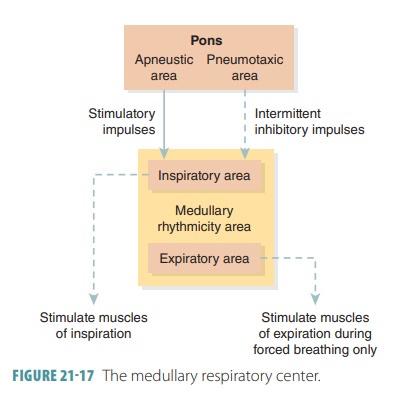

control respira-tory muscles. The most important parts comprise the medullary respiratory center,

which consists of the dorsal

and ventral respiratory groups and the respira-tory group of the pons (FIGURE 21-17).

The dorsal respiratory group is located near the root of

cranial nerve IX. It is important in stimulating the muscles of inspiration but

is still not fully under-stood. Increased impulses result in more forceful

muscle contractions and deeper breathing. Decreased impulses result in passive

expiration. It is known that the dorsal respiratory group integrates input from

chemoreceptors and peripheral stretch receptors. It communicates this

information to the ventral respiratory group.

The ventral respiratory group controls other respiratory muscles, mostly the intercostals and abdominals, to increase the force of expiration and sometimes to increase inspiratory efforts. It is believed to be a center of integration and generation of rhythm. It is a network of neurons extending from the spinal cord, through the ventral brain stem, to the pons–medulla junction. Some neurons fire during inspiration, whereas others fire during expiration. The inspiratory neurons send impulses along the phrenic and intercostal nerves, exciting the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles, respectively. Therefore, damage to the phrenic nerves can increase respira-tory rate. The expiratory neurons cause the output to stop and passive expiration to occur, as the inspiratory muscles relax and the lungs then recoil.

This inspiratory and expiratory cycling is contin-uous,

producing the normal respiratory rate of 12 to 15 breaths per minute.

Inspiratory phases last about two seconds, whereas expiratory phases last about

three seconds. Eupnea is the term

describing this nor-mal respiratory rate and rhythm. In severe hypoxia, the

ventral respiratory group causes the individual to gasp for air. This may be a

final effort to restore oxygen to the brain. When certain clustered neurons are

completely suppressed, respiration stops. Causes of this include overdoses of

alcohol or drugs such as morphine.

The basic rhythm of breathing may also be con-trolled by the

pontine respiratory group in the pons. This consists of several centers

influencing and modi-fying medullary neuron activities. The pontine group is

believed to make the transitions between inspiration and expiration and the

reverse, smoother processes. Lesions to the superior region of the pontine

respi-ratory group cause prolonged inspirations to occur, which is called apneustic breathing.

However, the rhythmic quality of breathing is not fully

understood. The most accepted theory is that normal respiratory rhythm is based

on reciprocal inhi-bition of interconnected networks of neurons in the medulla.

Instead of one set of “pacemaker neurons,” two sets of neurons inhibit each

other. Their activity occurs in cycles, and this generates respiratory rhythm.

Factors of Respiratory Rate and Depth

The depth of inspiration during breathing is based on the

level of activity of the respiratory center and its stimulation of motor

neurons that serve the respira-tory muscles. With more stimulation, increased

num-bers of motor units are excited. Therefore, respiratory muscles contract

with greater force. Respiratory rate is established by the length of time the

inspiratory center is active or how fast it is turned off. Deep breathing is

referred to as diaphragmatic breathing, while shallow breathing is known as

costal breathing.

Certain chemicals also affect respiratory rate and depth.

Important substances include CO2, hydrogen, and oxygen ions in the

arterial blood. Other factors include emotional states, lung stretching capability,

and levels of physical activity. Chemosensitive areas known as central chemoreceptors, located in the medulla oblongata,

sense CO2 and hydrogen ion changes in the cerebrospinal fluid. When

these levels change, respira-tory rate and TV are signaled to increase. More CO2

is exhaled, and both blood and cerebrospinal fluid levels of these chemicals

fall, decreasing breathing rate.

CO2 is the most important chemical regulator of

respiration. Arterial partial pressure of CO2 is usually 40 mm Hg,

maintained within 3 mm Hg of this level, mostly by how rising CO2

levels affect the central che-moreceptors. Hypercapnia is a condition in which CO2 accumulates in the

brain. The accumulating CO2 is hydrated and H2CO3

is formed. When the acid is dissociated, hydrogen ions are freed and pH drops.

This also happens when CO2 enters red blood cells.

Increased hydrogen ions excite the central chemore-ceptors,

which extensively synapse with the respiratory regulatory centers. Breathing

depth and rate, therefore, increase. Because alveolar ventilation is enhanced,

CO2 is quickly flushed out of the blood and pH rises. Alveolar

ventilation is doubled with an elevation of only 5 mm Hg in arterial partial

pressure of CO2. This is true even when there is no change in

arterial oxygen levels or pH. The response to elevated partial pressure of CO2

is even more extensive when partial pressure of oxygen and pH are lower

than normal. Increased ventilation is usually self-limited. It stops when there

is restoration of homeostatic blood partial pressure of CO2.

The rising levels of hydrogen ions within the brain increase

the activity of the central chemoreceptors, even though rising blood CO2

is the first stimulus. Although hydrogen does not easily diffuse across the

blood–brain barrier, CO2 accomplishes this with no problem.

Therefore, control of breathing while resting mostly is based on regulation of

hydrogen ion concen-tration in the brain.

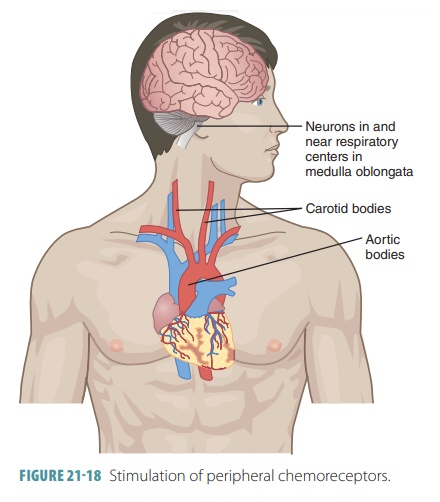

However, peripheral

chemoreceptors in the carotid and aortic bodies also help and are able to

sense changes in blood oxygen levels (FIGURE 21-18). Then, they increase the breathing rate, but this action

requires extremely low levels of blood oxygen to occur.

The depth of breathing is regulated by the inflation reflex, which occurs when stretched lung tissues

stimu-late stretch receptors in the visceral pleura, bronchioles, and alveoli.

The duration of inspiratory movements is shortened, preventing overinflation

of the lungs during forceful breathing. Emotional upset such as that caused by

fear and pain usually increase breathing rate. If breathing stops, even for a

short time, blood levels of CO2 and hydrogen ions rise and oxygen

levels fall. Chemoreceptors are stimulated and the urge to inhale increases,

overcoming the lack of oxygen. The deflation

reflex usually

only functions during forced exhalation and inhibits the expiratory centers while

stimulating the inspiratory centers when the lungs are deflating.

How Partial Pressure of Oxygen Influences Breathing

The peripheral chemoreceptors contain cells that are

sensitive to arterial levels of oxygen. These chemo-receptors lie in the aortic bodies of the aortic arch and the carotid bodies at the bifurcation of the com-mon

carotid arteries. Those in the carotid bodies are the main oxygen sensors.

Normally, reducing par-tial pressure of oxygen only affects ventilation

mini-mally. This primarily involves enhanced sensitivity of peripheral

receptors to increased partial pressure of CO2. For oxygen levels to

become a strong stimulus for increased ventilation, arterial partial pressure

of oxygen must drop greatly, to at least 60 mm Hg.

How Arterial pH Influences Breathing

Even during normal levels of oxygen and CO2,

changes to arterial pH can modify the rate and rhythm of breathing. Increased

ventilation occurring because of reduced arterial pH is controlled via the

peripheral chemoreceptors. This is in part because hydrogen ions do not cross

the blood–brain barrier. Changes in par-tial pressure of CO2 and

hydrogen ion concentration are related, yet different.

Reduced blood pH may be related to retention of CO2.

However, it may also occur because of meta-bolic reasons. These include lactic

acid accumulation because of exercise or fatty acid metabolite or ketone body accumulation because of

uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. No

matter what the reason, as arterial pH declines, the respiratory system will

attempt to com-pensate and raise the pH. This occurs by the increase of

respiratory rate and depth in an attempt to elimi-nate CO2 and H2CO3

from the blood.

How Higher Brain Centers Influence Breathing

Respiratory rate and depth are modified when pain or strong

emotions send signals to the respiratory centers. This occurs via the limbic

system, including the hypothalamus. Changes in body temperature also affect

respiration, with hotter temperatures increasing it and colder temperatures

decreasing it.

Conscious control of breathing can also occur. The cerebral

motor cortex sends impulses to the motor neurons, causing stimulation of

respiratory muscles. This bypasses the medullary centers. Holding the breath is

a limited function because the brain stem respiratory centers automatically

reinitiate breathing once CO2 levels in the blood become critical.

1. Describe the medullary respiratory center.

2. Are peripheral chemoreceptors as sensitive to levels of CO2

as they are to levels of oxygen?

3. Differentiate between the central and peripheral

chemoreceptors and their actions.

Related Topics