Relative Risk and Odds Ratios

| Home | | Advanced Mathematics |Chapter: Biostatistics for the Health Sciences: Categorical Data and Chi-Square Tests

The concepts of relative risk and odds ratios are derived from epidemiologic studies.

RELATIVE RISK AND ODDS RATIOS

The concepts of relative risk and odds ratios are

derived from epidemiologic studies. A thorough discussion of them is beyond

the scope of this text. We refer the reader to Friis and Sellers (1999) or

Lachin (2000) for in-depth coverage of these topics. However, we will review

them briefly here, because they are common mea-sures that are germane to any

treatment of categorical data.

The relative risk is used in cohort studies, which

are a type of prospective study in which persons who have different types of

exposure to risk factors for disease are fol-lowed prospectively, meaning that

disease-free subjects are followed over time and the occurrence of new cases of

disease is recorded.

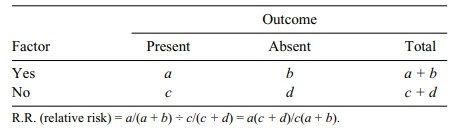

TABLE 11.10. 2 × 2 Table for Assessment of Relative Risk

The occurrence of new cases of disease (known as incidence) is compared between subjects who have an exposure of interest and those who do not. Consequently, the

subjects must be free from the dis-ease of interest before the exposure occurs,

and they must be observed after a period of time to ascertain the effects of

exposure. In a cohort study, the measure of associ-ation between exposure and

disease is known as the relative risk (R.R.).

Relative risk is a number that can vary from very

low (approaching 0) to “large.” A relative risk of l suggests that the risk of

an outcome of interest is equally bal-anced between those exposed and not

exposed to the factor. As relative risk increas-es above 1, the risk factor has

a stronger association with the study outcome. Table 11.10 presents the format

of a 2 × 2 table for assessment of relative risk; a calcula-tion example is

provided in Table 11.11.

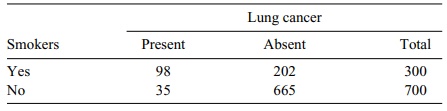

Researchers follow a cohort of 300 smokers and a

comparison cohort of non-smokers over a 20-year period. The relative risk of

lung cancer associated with smoking is 98/300 ÷ 35/700 = 6.53. These data

suggest that the smokers are 6.5 times more likely to develop lung cancer than

the nonsmokers. Sometimes the rela-tive risk can be less than 1. This value

suggests that the exposure factor is a protec-tive factor. For example, if the

incidence of lung cancer had been lower among the smokers, smoking would be a

protective factor for lung cancer!

A second type of major epidemiologic study is a

case-control study. This study is a type of retrospective study in which cases

(those who have a disease of interest) are compared with controls (those who do

not have the disease) with respect to ex-posure history.

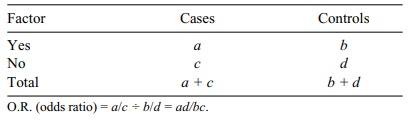

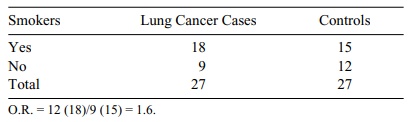

For example, we might also study the association

between smoking and lung cancer by using the case-control approach. A group of

lung cancer patients (the cases) and controls would be assessed for history of

smoking. The odds ratio (O.R.) is the measure of association between the factor

and outcome in a case-control study. In Table 11.12, we provide a 2 × 2 table

for assessment of an odds ratio. The corresponding calculation example is shown

in Table 11.13.

TABLE 11.11. Smoking and Lung Cancer Data for a Cohort Study

TABLE 11.12. 2 × 2 Table for Assessment of an Odds Ratio

TABLE 11.13. Smoking and Lung Cancer Data for a Case-Control Study

In this example, smokers were 1.6 times as likely

to develop lung cancer as non-smokers. Note that the odds ratio is a measure of

association that is interpreted in a similar way as a relative risk.

Note that throughout the foregoing examples we have

calculated only point esti-mates of relative risk. You might be interested in

confidence intervals or hypothesis tests. For example, if we could obtain a 95%

confidence interval for relative risk that did not include 1, we would be able

to reject the null hypothesis of no differ-ence at the 5% level. This topic is

outside the scope of the present text, but the in-terested reader can find the

asymptotic results needed for approximate confidence intervals on relative risk

in Lachin (2000), page 24.

Related Topics