Concept Maps

| Home | | Biochemistry |Chapter: Biochemistry : Amino Acids

Students sometimes view biochemistry as a list of facts or equations to be memorized, rather than a body of concepts to be understood. Details provided to enrich understanding of these concepts inadvertently turn into distractions.

CONCEPT MAPS

Students sometimes view

biochemistry as a list of facts or equations to be memorized, rather than a

body of concepts to be understood. Details provided to enrich understanding of

these concepts inadvertently turn into distractions. What seems to be missing

is a road map—a guide that provides the student with an understanding of how

various topics fit together to make sense. Therefore, a series of biochemical

concept maps have been created to graphically illustrate relationships between

ideas presented in a chapter and to show how the information can be grouped or

organized. A concept map is, thus, a tool for visualizing the connections

between concepts. Material is represented in a hierarchic fashion, with the

most inclusive, most general concepts at the top of the map and the more

specific, less general concepts arranged beneath. The concept maps ideally

function as templates or guides for organizing information, so the student can

readily find the best ways to integrate new information into knowledge they

already possess.

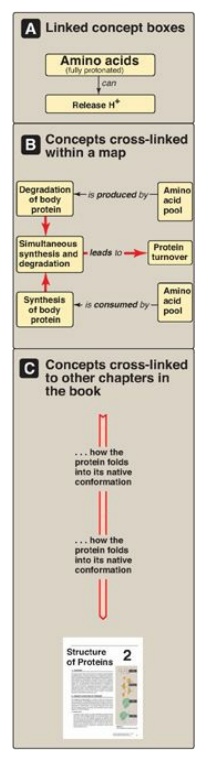

Figure 1.13 Symbols

used in concept maps.

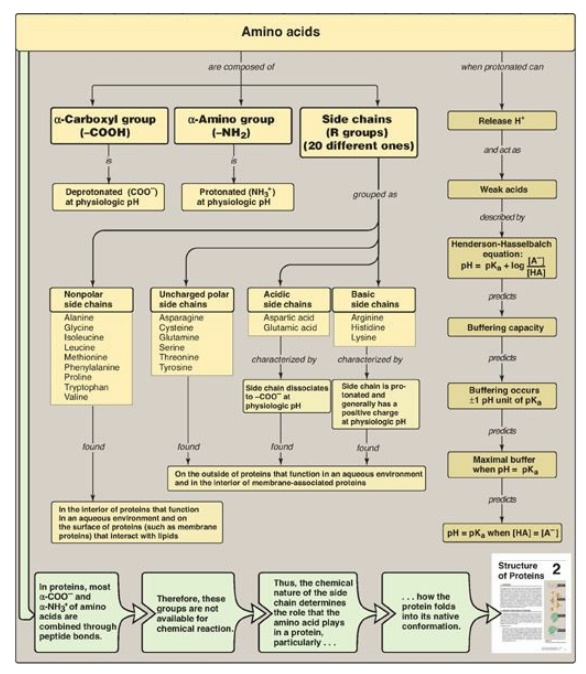

Figure 1.14

Key concept map for amino acids.

A. How is a concept map constructed?

1.Concept boxes and links: Educators define concepts as

“perceived regularities in events or objects.” In the biochemical maps,

concepts include abstractions (for example, free energy), processes (for

example, oxidative phosphorylation), and compounds (for example, glucose

6-phosphate). These broadly defined concepts are prioritized with the central

idea positioned at the top of the page. The concepts that follow from this

central idea are then drawn in boxes (Figure 1.13A). The size of the type

indicates the relative importance of each idea. Lines are drawn between concept

boxes to show which are related. The label on the line defines the relationship

between two concepts, so that it reads as a valid statement, that is, the connection

creates meaning. The lines with arrowheads indicate in which direction the

connection should be read (Figure 1.14).

2. Cross-links: Unlike linear flow charts or outlines, concept maps

may contain cross-links that allow the reader to visualize complex

relationships between ideas represented in different parts of the map (Figure

1.13B), or between the map and other chapters in this book (Figure 1.13C).

Cross-links can, thus, identify concepts that are central to more than one

topic in biochemistry, empowering students to be effective in clinical

situations and on the United States Medical Licensure Examination (USMLE) or

other examinations that require integration of material. Students learn to

visually perceive nonlinear relationships between facts, in contrast to

cross-referencing within linear text.

Related Topics